Humans know the surprising prick of a needle, the searing pain of a stubbed toe and the throbbing of a toothache. We can identify many types of pain and have multiple ways of treating it. But what about other species? How do the animals all around us experience pain? It’s important that we find out. We keep animals as pets, they enrich our environment, we farm many species for food, and we use them in experiments to advance science and human health. Animals are clearly important to us, so it’s equally important that we avoid causing them unnecessary pain.

For animals that are similar to us, like mammals, it's often obvious when they're hurting. But there's a lot that isn't obvious, like whether pain relievers that work on us also help them. And the more different an animal is from us, the harder it is to understand their experience. How do you tell whether a shrimp is in pain? A snake? A snail?

In vertebrates— including humans— pain can be split into two distinct processes. In the first, nerves in the skin sense something harmful and communicate that information to the spinal cord. There, motor neurons activate movements that make us rapidly jerk away from the threat. This is the physical recognition of harm called nociception. And nearly all animals, even those with very simple nervous systems, experience it. Without this ability, animals would be unable to avoid harm and their survival would be threatened.

The second part is the conscious recognition of harm. In humans, this occurs when the sensory neurons in our skin make a second round of connections via the spinal cord to the brain.

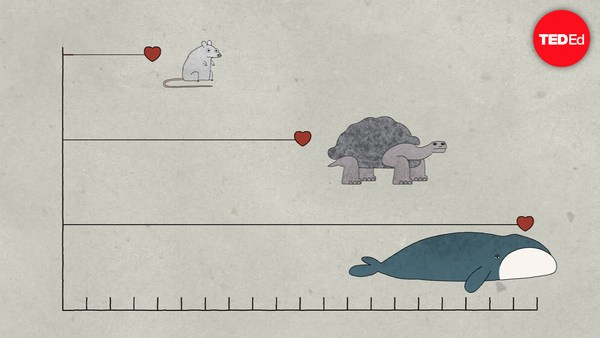

There, millions of neurons in multiple regions create the sensations of pain. For us, this is a very complex experience associated with emotions like fear, panic and stress, which we can communicate to others. But it’s harder to know exactly how animals experience this part the process, because most of them can’t show us what they feel.

However, we get clues from observing how animals behave. Wild, hurt animals are known to nurse their wounds, make noises to show their distress, and become reclusive. in the lab, scientists have discovered that animals like chickens and rats will self-administer pain-reducing drugs if they’re hurting. Animals also avoid situations where they’ve been hurt before, which suggests awareness of threats.

We’ve reached the point that research has made us so sure that vertebrates recognize pain that it’s illegal in many countries to needlessly harm these animals. But what about other types of animals, like invertebrates? These animals aren't legally protected, partly because their behaviors are harder to read. We can make good guesses about some of them, like oysters, worms and jellyfish. These are examples of animals that either lack a brain or have a very simple one. So an oyster may recoil when squirted with lemon juice, for instance, because of nociception. But with such a simple nervous system, it’s unlikely to experience the conscious part of pain.

Other invertebrate animals are more complicated, though. Like the octopus, which has a sophisticated brain and is thought to be one of the most intelligent invertebrate animals. Yet in many countries, people continue the practice of eating live octopus. We also boil live crayfish, shrimp, and crabs, even though we don't really know how they're affected either.

This poses an ethical problem, because we may be causing these animals unnecessary suffering. Scientific experimentation, though controversial, gives us some clues. Tests on hermit crabs show that they’ll leave an undesirable shell if they’re zapped with electricity. But stay if it’s a good shell. And octopi that might originally curl up an injured arm to protect it, will risk using it to catch prey. That suggests that these animals make value judgments around sensory input, instead of just reacting reflexively to harm. Meanwhile, crabs have been known to repeatedly rub a spot on their bodies where they’ve received an electric shock. And even sea slugs flinch when they know they’re about to receive a noxious stimulus. That means they have some memory of physical sensations.

We still have a lot to learn about animal pain. As our knowledge grows, it may one day allow us to live in a world where we don’t cause pain needlessly.