So, here's a prediction. If we get our cities right, we just might survive the 21st century. We get them wrong, and we're done for.

Cities are the most extraordinary experiment in social engineering that we humans have ever come up with. If you live in a city, and even if you live in a slum -- which 20 percent of the world's urban population does -- you're likely to be healthier, wealthier, better educated and live longer than your country cousins. There's a reason why three million people are moving to cities every single week. Cities are where the future happens first. They're open, they're creative, they're dynamic, they're democratic, they're cosmopolitan, they're sexy. They're the perfect antidote to reactionary nationalism. But cities have a dark side. They take up just three percent of the world's surface area, but they account for more than 75 percent of our energy consumption, and they emit 80 percent of our greenhouse gases. There are hundreds of thousands of people who die in our cities every single year from violence, and millions more who are killed as a result of car accidents and pollution. In Brazil, where I live, we've got 25 of the 50 most homicidal cities on the planet. And a quarter of our cities have chronic water shortages -- and this, in a country with 20 percent of the known water reserves.

So cities are dual-edged. Part of the problem is that, apart from a handful of megacities in the West and the Far East, we don't know that much about the thousands of cities in Africa, in Latin America, in Asia, where 90 percent of all future population growth is set to take place. So why this knowledge gap? Well, part of the problem is that we still see the world through the lens of nation-states. We're still locked in a 17th-century paradigm of parochial national sovereignty. And yet, in the 1600's, when nation-states were really coming into their own, less than one percent of the world's population resided in a city. Today, it's 54 percent. And by 2050, it will be closer to 70 percent. So the world has changed. We have these 193 nation-states, but we have easily as many cities that are beginning to rival them in power and influence.

Just look at New York. The Big Apple has 8.5 million people and an annual budget of 80 billion dollars. Its GDP is 1.5 trillion, which puts it higher than Argentina and Australia, Nigeria and South Africa. Its roughly 40,000 police officers means it has one of the largest police departments in the world, rivaling all but the largest nation-states. But cities like New York or São Paulo or Johannesburg or Dhaka or Shanghai -- they're punching above their weight economically, but below their weight politically. And that's going to have to change. Cities are going to have to find their political voice if we want to change things.

Now, I want to talk to you a little bit about the risks that cities are facing -- some of the big mega-risks. I'm also going to talk to you briefly about some of the solutions. I'm going to do this using a big data visualization that was developed with Carnegie Mellon's CREATE Lab and my institute, along with many, many others. I want you to first imagine the world not as made up of nation-states, but as made up of cities. What you see here is every single city with a population of a quarter million people or more. Now, without going into technical detail, the redder the circle, the more fragile that city is, and the bluer the circle, the more resilient. Fragility occurs when the social contract comes unstuck. And what we tend to see is a convergence of multiple kinds of risks: income inequality, poverty, youth unemployment, different issues around violence, even exposure to droughts, cyclones and earthquakes. Now obviously, some cities are more fragile than others.

The good news, if there is any, is that fragility is not a permanent condition. Some cities that were once the most fragile cities in the world, like Bogotá in Colombia or Ciudad Juárez in Mexico, have now fallen more around the national average. The bad news is that fragility is deepening, especially in those parts of the world that are most vulnerable, in North Africa, the Middle East, in South Asia and Central Asia. There, we're seeing fragility rising way beyond scales we've ever seen before. When cities become too fragile they can collapse, tip over and fail. And when that happens, we have explosive forms of migration: refugees.

There are more than 22 million refugees in the world today, more than at any other time since the second world war. Now, there's not one refugee crisis; there are multiple refugee crises. And contrary to what you might read in the news, the vast majority of refugees aren't fleeing from poor countries to wealthy countries, they're moving from poor cities into even poorer cities -- often, cities nearby. Every single dot on this map represents an agonizing story of struggle and survival. But I want to briefly tell you about what's not on that map, and that's internal displacement. There are more than 36 million people who have been internally displaced around the world. These are people living in refugee-like conditions, but lacking the equivalent international protection and assistance. And to understand their plight, I want to zoom in briefly on Syria.

Syria suffered one of the worst droughts in its history between 2007 and 2010. More than 75 percent of its agriculture and 85 percent of its livestock were wiped out. And in the process, over a million people moved into cities like Aleppo, Damascus and Homs. As food prices began to rise, you also had equivalent levels of social unrest. And when the regime of President Assad began cracking down, you had an explosion of refugees. You also had over six million internally displaced people, many of whom when on to become refugees. And they didn't just move to neighboring countries like Jordan or Lebanon or Turkey. They also moved up north towards Western Europe. See, over 1.4 million Syrians made the perilous journey through the Mediterranean and up through Turkey to find their way into two countries, primarily: Germany and Sweden.

Now, climate change -- not just drought, but also sea level rise, is probably one of the most severe existential threats that cities face. That's because two-thirds of the world's cities are coastal. Over 1.5 billion people live in low-lying, flood-prone coastal areas. What you see here is a map that shows sea level rise in relation to changes in temperature. Climate scientists predict that we're going to see anywhere between three and 30 feet of sea level rise this side of the century. And it's not just low island nation-states that are going to suffer -- Kiribati or the Maldives or the Solomons or Sri Lanka -- and they will suffer, but also massive cities like Dhaka, like Hong Kong, like Shanghai. Cities of 10, 20, 30 million people or more are literally going to be wiped off the face of this earth. They're going to have to adapt, or they're going to die.

I want to take you also all the way over to the West, because this isn't just a problem in Asia or Africa or Latin America, this is a problem also in the West. This is Miami. Many of you know Miami is one of the wealthiest cities in the United States; it's also one of the most flood-prone. That's been made painfully evident by natural disasters throughout 2017. But Miami is built on porous limestone -- a swamp. There's no way any kind of flood barrier is going to keep the water from seeping in. As we scroll back, and we look across the Caribbean and along the Gulf, we begin to realize that those cities that have suffered worst from natural crises -- Port-au-Prince, New Orleans, Houston -- as severe and as awful as those situations have been, they're a dress rehearsal for what's to come.

No city is an island. Every city is connected to its rural hinterland in complex ways -- often, in relation to the production of food. I want to take you to the northern part of the Amazon, in Rondônia. This is one of the world's largest terrestrial carbon sinks, processing millions of carbon every single year. What you see here is a single road over a 30-year period. On either side you see land being cleared for pasture, for cattle, but also for soy and sugar production. You're seeing deforestation on a massive scale. The red area here implies a net loss of forest over the last 14 years. The blue, if you could see it -- there's not much -- implies there's been an incremental gain. Now, as grim and gloomy as the situation is -- and it is -- there is a little bit of hope.

See, the Brazilian government, from the national to the state to the municipal level, has also introduced a whole range -- a lattice -- of parks and protected areas. And while not perfect, and not always limiting encroachment, they have served to tamp back deforestation. The same applies not just in Brazil but all across the Americas, into the United States, Canada and around the world. So let's talk about solutions. Despite climate denial at the highest levels, cities are taking action. You know, when the US pulled out of the Paris Climate Agreement, hundreds of cities in the United States and thousands more around the world doubled down on their climate commitments.

(Applause)

And when the White House cracked down on so-called "undocumented migrants" in sanctuary cities, hundreds of cities and counties and states sat up in defiance and refused to enact that order.

(Applause)

So cities are and can take action.

But we're going to need to see a lot more of it, especially in the global south. You see, parts of Africa and Latin America are urbanizing before they industrialize. They're growing at three times the global average in terms their population. And this is putting enormous strain on infrastructure and services. Now, there is a golden opportunity. It's a small opportunity but a golden one: in the next 10 to 20 years, to really start designing in principles of resilience into our cities. There's not one single way of doing this, but there are a number of ways that are emerging. And I've spoken with hundreds of urban planners, development specialists, architects and civic activists, and a number of recurring principles keep coming out. I just want to pass on six.

First: cities need a plan and a strategy to implement it. I mean, it sounds crazy, but the vast majority of world cities don't actually have a plan or a vision. They're too busy putting out daily fires to think ahead strategically. I mean, every city wants to be creative, happy, liveable, resilient -- who doesn't? The challenge is, how do you get there? And urban governance plays a key role. You could do worse than take a page from the book of Singapore. In 1971, Singapore set a 50-year urban strategy and renews it every five years. What Singapore teaches us is not just the importance of continuity, but also the critical role of autonomy and discretion. Cities need the power to be able to issue debt, to raise taxes, to zone effectively, to build affordable housing. What cities need is nothing less than a devolution revolution, and this is going to require renegotiating the terms of the contract with a nation-state.

Second: you've got to go green. Cities are already leading global decarbonization efforts. They're investing in congestion pricing schemes, in climate reduction emission targets, in biodiversity, in parks and bikeways and walkways and everything in between. There's an extraordinary menu of options they have to choose from. One of the great things is, cities are already investing heavily in renewables -- in solar and wind -- not just in North America, but especially in Western Europe and parts of Asia. There are more than 8,000 cities right now in the world today with solar plants. There are 300 cities that have declared complete energy autonomy. One of my favorite stories comes from Medellín, which invested in a municipal hydroelectric plant, which doesn't only service its local needs, but allows the city to sell excess energy back onto the national grid. And it's not alone. There are a thousand other cities just like it.

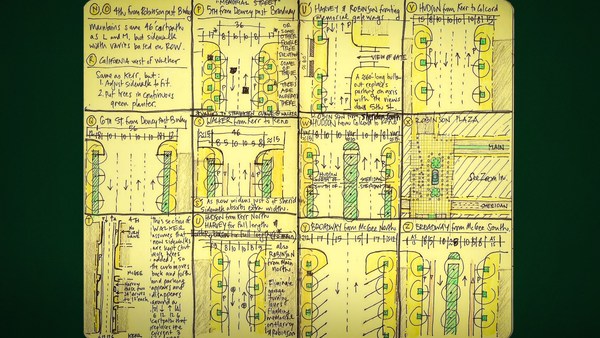

Third: invest in integrated and multi-use solutions. The most successful cities are those that are going to invest in solutions that don't solve just one problem, but that solve multiple problems. Take the case of integrated public transport. When done well -- rapid bus transit, light rail, bikeways, walkways, boatways -- these can dramatically reduce emissions and congestion. But they can do a lot more than that. They can improve public health. They can reduce dispersion. They can even increase safety. A great example of this comes from Seoul. You see, Seoul's population doubled over the last 30 years, but the footprint barely changed. How? Well, 75 percent of Seoul's residents get to work using what's been described as one of the most extraordinary public transport systems in the world. And Seoul used to be car country.

Next, fourth: build densely but also sustainably. The death of all cities is the sprawl. Cities need to know how to build resiliently, but also in a way that's inclusive. This is a picture right here of Dallas-Fort Worth. And what you see is its population also doubled over the last 30 years. But as you can see, it spread into edge cities and suburbia as far as the eye can see. Cities need to know when not to build, so as not to reproduce urban sprawl and slums of downward accountability. The problem with Dallas-Forth Worth is just five percent of its residents get to work using public transport -- five. Ninety-five percent use cars, which partly explains why it's got some of the longest commuting times in North America. Singapore, by contrast, got it right. They built vertically and built in affordable housing to boot.

Fifth: steal. The smartest cities are nicking, pilfering, stealing, left, right and center. They don't have time to waste. They need tomorrow's technology today, and they're going to leapfrog to get there. This is New York, but it's not just New York that's doing a lot of stealing, it's Singapore, it's Seoul, it's Medellín. The urban renaissance is only going to be enabled when cities start borrowing from one another.

And finally: work in global coalitions. You know, there are more than 200 inner-city coalitions in the world today. There are more city coalitions than there are coalitions for nation-states. Just take a look at the Global Parliament of Mayors, set up by the late Ben Barber, who was driving an urban rights movement. Or consider the C40, a marvelous network of cities that has gathered thousands together to deliver clean energy. Or look at the World Economic Forum, which is developing smart city protocols. Or the 100 Resilient Cities initiative, which is leading a resilience revival. ICLEI, UCLG, Metropolis -- these are the movements of the future. What they all realize is that when cities work together, they can amplify their voice, not just on the national stage, but on the global stage. And with a voice comes, potentially, a vote -- and then maybe even a veto.

When nation-states default on their national sovereignty, cities have to step up. They can't wait. And they don't need to ask for permission. They can exert their own sovereignty. They understand that the local and the global have really, truly come together, that we live in a global, local world, and we need to adjust our politics accordingly. As I travel around the world and meet mayors and civic leaders, I'm amazed by the energy, enthusiasm and effectiveness they bring to their work. They're pragmatists. They're problem-solvers. They're para-diplomats. And in this moment of extraordinary international uncertainty, when our multilateral institutions are paralyzed and our nation-states are in retreat, cities and their leaders are our new 21st-century visionaries. They deserve -- no, they have a right to -- a seat at the table.

Thank you.

(Applause)