Some of you have heard the story before, but, in fact, there's somebody in the audience who's never heard this story in front of an audience before, so I'm a little more nervous than I normally am telling this story. I used to be a photographer for many years. In 1978, I was working for "TIME Magazine" and I was given a three-day assignment to photograph Amerasian children, children who had been fathered by American GIs all over Southeast Asia, and then abandoned -- 40,000 children all over Asia. I had never heard the word Amerasian before. I spent a few days photographing children in different countries, and like a lot of photographers and a lot of journalists, I always hoped that when my pictures are published, they might actually have an effect on a situation, instead of just documenting it.

So, I was so disturbed by what I saw and I was so unhappy with the article that ran afterwards, that I decided I would take six months off. I was 28 years old. I decided I would find six children in different countries, and actually go spend some time with the kids, and try to tell their story a little bit better than I thought I had done for Time magazine. In the course of doing the story, I was looking for children who hadn't been photographed before, and the Pearl Buck Foundation told me that they worked with a lot of Americans who were donating money to help some of these kids. And a man told me, who ran the Pearl Buck Foundation in Korea, that there was a young girl, who was 11 years old, being raised by her grandmother. And the grandmother had never let any Westerners see her. Every time any Westerners came to the village, she hid the girl. Of course, I was immediately intrigued. I saw photographs of her and I thought I wanted to go. And the guy just told me, "This grandmother -- there's no way she's ever going to let you meet this girl that's she's raising."

I took a translator with me and went to this village, found the grandmother, sat down with her. And to my astonishment, she agreed to let me photograph her granddaughter. And I was paying for this myself, so I asked the translator if it would be OK if I stayed for the week. I had a sleeping bag. The family had a small shed on the side of the house, so I said, "Could I sleep in my sleeping bag in the evenings?" And I just told the little girl, whose name was Eun-Sook Lee, that if I ever did anything to embarrass her -- she didn't speak a word of English, although she looked very American -- she could put up her hand and say, "Stop," and I would stop taking pictures. Then my translator left. I couldn't speak a word of Korean. This is the first night I met Eun-Sook. Her mother was still alive. She was not raising her, her grandmother was raising her. And what struck me immediately was how in love the two of these people were. The grandmother was incredibly fond, deeply in love with this little girl. They slept on the floor at night. The way they heat their homes in Korea is to put bricks under the floors, so the heat radiates from underneath the floor. Eun-Sook was 11 years old.

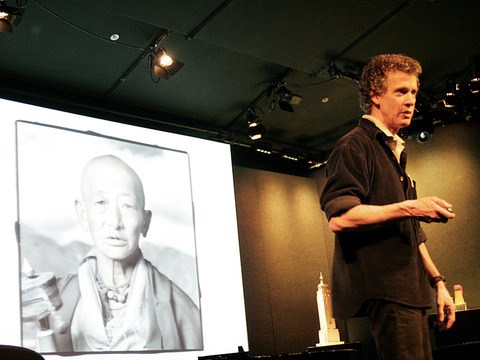

I had photographed, as I said, a lot of these kids. Eun-Sook was the fifth child that I found to photograph. And almost universally, amongst all the kids, they were really psychologically damaged by having been made fun of, ridiculed, picked on and been rejected. And Korea was probably the place I found to be the worst for these kids. And what struck me immediately in meeting Eun-Sook was how confident she appeared to be, how happy she seemed to be in her own skin. And remember this picture, because I'm going to show you another picture later. She looks much like her grandmother, although she looks so Western.

I decided to follow her to school. This is the first morning I stayed with her. This is on the way to school. This is the morning assembly outside her school. And I noticed that she was clowning around. When the teachers would ask questions, she'd be the first person to raise her hand. Again, not at all shy or withdrawn, or anything like the other children that I'd photographed. The first one to go to the blackboard to answer questions. Getting in trouble for whispering into her best friend's ears. And one of the other things I said to her through the translator -- again, this thing about saying stop -- was to not pay attention to me. So she really just completely ignored me most of the time. I noticed that at recess, she was the girl who picked the other girls to be on her team. It was very obvious, from the beginning, that she was a leader. This is on the way home. And that's North Korea up along the hill. This is up along the DMZ. They would actually cover the windows every night, so that light couldn't be seen, because the South Korean government has said for years that the North Koreans may invade at any time. So the closer you were to North Korea, the more terrifying it was.

Very often at school, I'd be taking pictures, and she would whisper into her girlfriends' ears, and then look at me and say, "Stop." And I would stand at attention, and all the girls would crack up, and it was sort of a little joke.

(Laughter)

The end of the week came and my translator came back, because I'd asked her to come back, so I could formally thank the grandmother and Eun-Sook. And in the course of the grandmother talking to the translator, the grandmother started crying. And I said to my translator, "What's going on, why is she crying?" And she spoke to the grandmother for a moment, and then she started getting tears in her eyes. And I said, "What did I do? Why is everyone crying?" And the translator said, "The grandmother says that she thinks she's dying, and she wants to know if you would take Eun-Sook to America with you." And I said, "I'm 28 years old and I live in hotels, and I'm not married." I mean, I had fallen in love with this girl, but you know, emotionally I was about 12 years old. If you know of photographers, the joke is it's the finest form of delayed adolescence ever invented. "Sorry, I have to go on an assignment, I'll be back" -- and then you never come back.

So I asked the translator why she thought she was dying. Can I get her to a hospital? Could I pay to get her a doctor? And she refused any help at all. So when I got outside, I gave the translator some money and said, "Go back and see if you can do something." And I gave the grandmother my business card. And I said, "If you're serious, I will try to find a family for her." And I immediately wrote a letter to my best friends in Atlanta, Georgia, who had an 11-year-old son. And my best friend had mistakenly one day said something about wishing he had another child. So my friends Gene and Gayle had not heard from me in about a year, and suddenly I was calling, saying "I'm in Korea and I've met this extraordinary girl." And I said, "The grandmother thinks she's sick, but I think maybe we would have to bring the grandmother over also." And I said, "I'll pay for the ... " I mean, I had this whole sort of picture. So anyway, I left. And my friends actually said they were very interested in adopting her. And I said, "Look, I think I'll scare the grandmother to death, if I tell her that you're willing to adopt her. I want to go back and talk to her." But I was off on assignment. I figured I'd come back in a couple of weeks and talk to the grandmother.

And on Christmas Day, I was in Bangkok with a group of photographers and got a telegram -- back in those days, you got telegrams -- from Time magazine saying someone in Korea had died and left their child in a will to me. Did I know anything about this? Because I hadn't told them what I was doing, because I was so upset with the story they'd run. So, I went back to Korea, and I went back to Eun-Sook's village, and she was gone. And the house that I had spent time in was empty. It was incredibly cold. No one in the village would tell me where Eun-Sook was, because the grandmother had always hidden her from Westerners. And they had no idea about this request that she'd made of me. So I finally found Myung Sung, her best friend that she used to play with after school every day. And Myung Sung, under some pressure from me and the translator, gave us an address on the outside of Seoul. And I went to that address and knocked on the door, and a man answered the door. It was not a very nice area of Seoul, there were mud streets outside of it. And I knocked on the door and Eun-Sook answered the door, and her eyes were bloodshot, and she seemed to be in shock. She didn't recognize me -- there was no recognition whatsoever. And this man came to the door and kind of barked something in Korean. And I said to the translator, "What did he say?" And she said, "He wants to know who you are." And I said, "Tell him that I am a photographer." I started explaining who I was, and he interrupted. And she said, "He says he knows who you are, what do you want?" I said, "Well, tell him that I was asked by this little girl's grandmother to find a family for her." And he said, "I'm her uncle, she's fine, you can leave now."

So I was -- The door was being slammed in my face, it's incredibly cold, and I'm trying to think, "What would the hero do in a movie, if I was writing this as a movie script?" So I said, "It's really cold, I've come a very long way, do you mind if I come in for a minute? I'm freezing." So the guy reluctantly let us in and we sat down on the floor. And as we started talking, I saw him yell something, and Eun-Sook came and brought us some food. And I had this whole mental picture of -- sort of like Cinderella. I sort of had this picture of this incredibly wonderful, bright, happy little child, who now appeared to be very withdrawn, being enslaved by this family. And I was really appalled, and I couldn't figure out what to do. And the more I tried talking to him, the less friendly he was getting. So finally I said "Look," -- this is all through the translator, because, you know, I don't speak a word of Korean -- and I said, "Look, I'm really glad that Eun-Sook has a family to live with. I was very worried about her. I made a promise to her grandmother, your mother, that I would find a family, and I'm so happy that you're going to take care of her. But I bought an airline ticket and I'm stuck here for a week. I'm staying in a hotel downtown. Would you like to come and have lunch tomorrow? And you can practice your English." Because he told me -- I was trying to ask him questions about himself.

And so I went to the hotel, and I found two older Amerasians. A girl whose mother had been a prostitute, and she was a prostitute, and a boy who'd been in and out of jail. And I said to them, "Look, there's a little girl who has a tiny chance of getting out of here and going to America. I don't know if it's the right decision or not, but I would like you to come to lunch tomorrow and tell the uncle what it's like to walk down the street, what people say to you, what you do for a living. I want him to understand what happens if she stays here. And I could be wrong, I don't know, but I wish you would come tomorrow."

So, these two came to lunch and we got thrown out of the restaurant. They were yelling at him, it got to be really ugly. We went outside, and he was just furious. And I knew I had totally blown this thing. Here I was again, trying to figure out what to do. And he started yelling at me, and I said to the translator, "Tell him to calm down, what is he saying?" And she said, "He's saying, 'Who the hell are you to walk into my house, some rich American with your cameras around your neck, accusing me of enslaving my niece? This is my niece, I love her, she's my sister's daughter. Who the hell are you to accuse me of something like this?'" And I said, you know, "Look, you're absolutely right. I don't pretend to understand what's going on here. All I know is, I've been photographing a lot of these children. I'm in love with your niece, I think she's an incredibly special child." And I said, "Look, I will fly my friends over here from the United States if you want to meet them, to see if you approve of them. I just think that -- what little I know about the situation, she has very little chance here of having the kind of life that you probably would like her to have."

So, everyone told me afterwards that inviting the prospective parents over was, again, the stupidest thing I could have possibly done, because who's ever good enough for your relative? But he invited me to come to a ceremony they were having that day for her grandmother. And they actually take items of clothing and photographs, and they burn them as part of the ritual. And you can see how different she looks just in three months. This was now, I think, early February. And the pictures before were taken in September. Well, there was an American Maryknoll priest that I had met in the course of doing the story, who had 75 children living in his house. He had three women helping him take care of these kids. And so I suggested to the uncle that we go down and meet Father Keane to find out how the adoption process worked. Because I wanted him to feel like this was all being done very much above board.

So, this is on the way down to the orphanage. This is Father Keane. He's just a wonderful guy. He had kids from all over Korea living there, and he would find families for these kids. This is a social worker interviewing Eun-Sook. Now, I had always thought she was completely untouched by all of this, because the grandmother, to me, appeared to be sort of the village wise woman -- throughout the day, I noticed people kept coming to visit her grandmother. And I always had this mental picture that even though they may have been one of the poorer families in the village, they were one of the most respected. And I always felt that the grandmother had kind of demanded, and insisted, that the villagers treat Eun-Sook with the same respect they treated her. Eun-Sook stayed at Father Keane's, and her uncle agreed to let her stay there until the adoption went through. He actually agreed to the adoption.

And I went off on assignment and came back a week later, and Father Keane said, "I've got to talk to you about Eun-Sook." I said, "Oh God, now what?" And he takes me into this room, closes the door and says, "I have 75 children here in the orphanage, and it's total bedlam." There's clothes, there's kids. Three adults and 75 kids -- you can imagine. And he said, "The second day she was here she made up a list of all of the names of the older kids and the younger kids. And she assigned one of the older kids to each of the younger kids. And then she set up a work detail list of who cleaned the orphanage on what day." And he said, "She's telling me that I'm messy and I have to clean up my room." And he said, "I don't know who raised her, but she's running the orphanage, and she's been here three days."

(Laughter)

This was movie day that she organized where all the kids went to the movies. A lot of the kids who had been adopted wrote back to the other kids, telling them what their life was like with their new families. So it was a really big deal when the letters showed up. This is a woman who is now working at the orphanage, whose son had been adopted. Gene and Gayle started studying Korean the moment they had gotten my first letter. They really wanted to be able to welcome Eun-Sook into their family. And one of the things Father Keane told me when I came back from one of these trips -- Eun-Sook had chosen the name Natasha, which I understood was from her watching a "Rocky and Bullwinkle" cartoon on the American Air Force station. This may be one of those myth-buster things that we'll have to clear up here, in a minute.

So, my friend Gene flew over with his son, Tim. Gayle couldn't come. And they spent a lot of time huddled over a dictionary. And this was Gene showing the uncle where Atlanta was on the map, where he lived. This is the uncle signing the adoption papers. Now, we went out to dinner that night to celebrate. The uncle went back to his family and Natasha and Tim and Gene and I went out to dinner. And Gene was showing Natasha how to use a knife and fork, and then Natasha was returning the utensil lessons. We went back to our hotel room, and Gene was showing Natasha also where Atlanta was. This is the third night we were in Korea. The first night we'd gotten a room for the kids right next to us.

I'd been staying in this room for about three months -- it was a little 15-story Korean hotel. The second night, we didn't keep the kids' room, because we slept on the floor with all the kids at the orphanage. And the third night, we came back -- we'd just gone out to dinner, where you saw the pictures -- and we got to the front desk, and the guy said, "There's no other free rooms on your floor tonight, you can put the kids five floors below you." And Gene and I looked at each other and said, "We don't want two 11-year-olds five floors away." So his son said, "I have a sleeping bag, I'll sleep on the floor." And I said, "I have one too." So Tim and I slept on the floor, Natasha got one bed, Gene got the other -- kids pass out, it's been very exciting for three days.

We're lying in bed, and Gene and I are talking about how cool we are. We said, "That was so great, we saved this little girl's life." We were just like, you know, just full of ourselves. And we fall asleep -- and I've been in this room for a couple of months now. And they always overheat the hotels in Korea terribly, so during the day I always left the window open. And then about midnight, they turn the heat off in the hotel. So at 1am, the whole room would be like 20 below zero, and I'd get up. I'd been doing this every night I'd been there. So, sure enough, it's one o'clock, room's freezing, I go to close the window and I hear people shouting outside, and I thought, "Oh, the bars must have just gotten out." I don't speak Korean, but I'm hearing these voices, and I'm not hearing anger, I'm hearing terror. So I open the window and I look out, and there's flames coming up the side of our hotel, and the hotel's on fire. So I run over to Gene and I wake him up, and I say, "Don't freak out, I think the hotel's on fire." And now there's smoke and flames coming by our windows -- we're on the 11th floor. So the two of us were just like, "Oh my God, oh my God."

So we're trying to get Natasha up, and we can't talk to her. You know what kids are like when they've been asleep for like an hour, it's like they took five Valiums -- they're all over the place. And we can't talk to her. His son had the L.L.Bean bootlaces, and we're trying to do up his laces. So we try to get to the door, we run to the door, we open the door, and it's like walking into a blast furnace. There's people screaming, the sound of glass breaking, weird thumps. And the whole room filled with smoke in about two seconds. And Gene turns around and says, "We're not going to make it." And he closes the door, and the whole room is now filled with smoke. We're all choking, and there's smoke pouring through the vents, under the doors. There's people screaming. I just remember this unbelievable -- just utter chaos.

I remember sitting near the bed, and I had two overwhelming feelings. One was absolute terror. "Oh, please God, I just want to wake up. This has got to be a nightmare, this can't be happening. Please, I just want to wake up." And the other is unbelievable guilt. Here I've been playing God with my friends' lives, my friends' son, with Natasha's life, and this what you get when you try playing God, is you hurt people. I remember just being so frightened and terrified. And Gene, who's lying on the floor, says, "We've got to soak towels." I said, "What?" "We've got to soak towels. We're going to die from the smoke." So got towels and put them over our faces and the kids' faces. Then he said, "Do you have gaffer's tape?" "What?" "Do you have gaffer's tape?" I said, "Somewhere in my Halliburton." He says, "We've got to stop the smoke. That's all we can do." I mean, Gene -- thank God for Gene. So we put the room service menus over the vents in the wall, we put blankets at the bottom of the door, we put the kids on the windowsill to try to get some air. And there was a new building, going up, that was being built right across the street from our hotel. And there, in the building, were photographers, waiting for people to jump. Eleven people ended up dying in the fire. Five people jumped and died, other people were killed by the smoke. And there's this loud thumping on the door after about 45 minutes in all this, and people were shouting in Korean. And I remember -- Natasha didn't want us opening the door -- sorry, I was trying not to open the door, because we'd spent so much time barricading the room. I didn't know who it was, I didn't know what they wanted, and Natasha could tell they were firemen trying to get us out. I remember a sort of a tussle at the door, trying to get the door open.

In any case, 12 hours later -- I mean, they put us in the lobby. Gene ended up using his coat, and his fist in the coat, to break open a liquor cabinet. People were lying on the floor. It was one of just the most horrifying nights. And then 12 hours later, we rented a car, as we had planned to, and drove back to Natasha's village. And we kept saying, "Do you realize we were dying in a hotel fire, like eight hours ago?" It's so weird how life just goes on. Natasha wanted to introduce her brother and father to all the villagers, and the day we showed up turned out to be a 60-year-old man's birthday. This guy's 60 years old. So it turned into a dual celebration, because Natasha was the first person from this village ever to go to the United States. So, these are the greenhouse tents. This is the elders teaching Gene their dances. We drank a lot of rice wine. We were both so drunk, I couldn't believe it.

This is the last picture before Gene and Tim headed back. The adoption people told us it was going to take a year for the adoption to go through. Like, what could you do for a year? So I found out the name of every official on both the Korean and American side, and I photographed them, and told them how famous they were going to be when this book was done. And four months later, the adoption papers came through. This is saying goodbye to everybody at the orphanage. This is Father Keane with Natasha at the bus stop. Her great aunt at the airport. I had a wonderful deal with Cathay Pacific airlines for many years, where they gave me free passes on all their airlines in return for photography. It was like the ultimate perk. And the pilot, I actually knew -- because they used to let me sit in the jump seat, to tell you how long ago this was. This is a TriStar, and so they let Natasha actually sit in the jump seat. And the pilot, Jeff Cowley, actually went back and adopted one of the other kids at the orphanage after meeting Natasha.

This is 28 hours later in Atlanta. It's a very long flight. Just to make things even crazier, Gayle, Natasha's new mom, was three days away from giving birth to her own daughter. You know, if you were writing this, you'd say, "No, we've got to write the script differently." This is the first night showing Natasha her new cousins and uncles and aunts. Gene and Gayle know everyone in Atlanta -- they're the most social couple imaginable. So, at this point, Natasha doesn't speak a word of English, other than what little Father Keane taught her. This is Kylie, her sister, who's now a doctor, on the right. This is a deal I had with Natasha, which is that when we got to Atlanta she could cut off my beard. She never liked it very much.

She learned English in three months. She entered seventh grade at her own age level. Pledge of Allegiance for the first time. This is her cooking teacher. Natasha told me a lot of the kids thought she was stuck up, because they would talk to her and she wouldn't answer, and they didn't realize she didn't speak English very well. But what I noticed, again as an observer, was she was choosing who was going to be on her team, and seemed to be very popular very, very quickly. Now, remember the picture, how much she looked like her grandmother, at the beginning? People were always telling Natasha how much she looks like her mother, Gayle.

(Laughter)

This is a tense moment in the first football game, I think. And Kylie -- I mean, it was almost like Kylie was her own child. She's being baptized. Now, a lot of parents, when they adopt, actually want to erase their children's history. And Gayle and Gene did the complete opposite. They were studying Korean; they bought Korean clothes. Gene even did a little tile work in the kitchen, which was that, "Once upon a time, there was a beautiful girl that came from the hills of Korea to live happily ever after in Atlanta."

She hates this picture -- it was her first job. She bought a bright red Karmann Ghia with the money she made working at Burger King. The captain of the cheerleaders. Beauty pageant. Used to do their Christmas card every year. Gene's been restoring this car for a million years.

Kodak hired Natasha to be a translator for them at the Olympics in Korea. Her future husband, Jeff, was working for Canon cameras, and met Natasha at the Olympic Village. This is her first trip back to Korea. So there's her uncle. This is her half sister. She went back to the village. That's her best friend's mother. And I always thought that was a very Annie Hall kind of outfit.

(Laughter)

It's just, you know, it was just so interesting, just to watch -- this is her mother in the background there. This is Natasha's wedding day. Gene is looking a little older. This is Sydney, who's going to be three years old in a couple of days. And there's Evan.

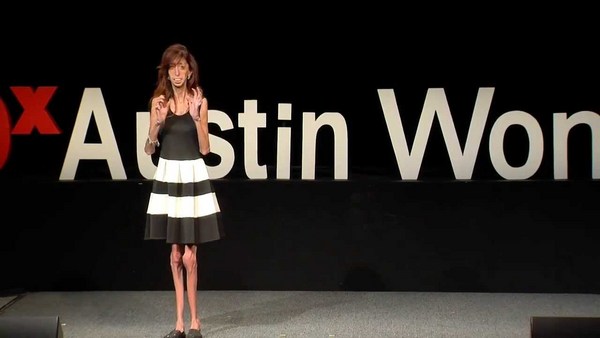

And Natasha, would you just come up, for a second, just maybe to say hello to everybody?

(Applause)

Natasha's actually never heard me tell the story. You know, we've looked at the pictures together.

Natasha: I've seen pictures millions of times, but today was the first time I'm actually seeing him give the whole presentation. I started crying.

Rick Smolan: There's about 40 things she's going to tell me, "That wasn't what happened." Natasha: I'll tell you that later.

RS: Anyway, thank you, Mike and Richard, so much for letting us tell the story.

Thank you, all of you.

(Applause)