The world has lost 68 percent of its wildlife populations in under 50 years, and there are people around the world working to protect and grow the wildlife that is left. In Africa, however, the approach to conserving this wildlife has almost always involved a separation of people from nature, the involvement, but never leadership, from local people, and a problem statement that has often come from outside our continent.

Basically years ago, colonial governments decided that we, as Africans, were not fit to take care of our own wildlife. And so people who had lived alongside wildlife for generations were removed from their ancestral lands and called new names. Poachers, encroachers, squatters. The story of conservation, as a result, has almost always then involved only a foreign scientist with a clipboard or a guy in green with a gun, there to protect that wildlife from everyone else. The rest of us have never existed in this story. And those who came to save species, came from the outside. And when they came, they were labeled heroes. They had to teach local people how to live alongside wildlife on the fringes of wild lands that they used to own.

This has created two distinct problems. One, because we don't often tell our own stories, it means that those who are closest to the wildlife are not seen as invested in conserving that wildlife compared to those who've come from the outside. And because foreign conservationists have sometimes not taken into consideration the needs of local people, they are then seen as caring more for animal life than for human life.

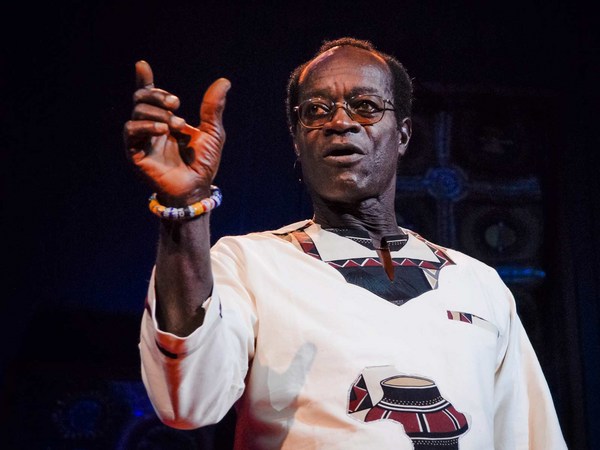

If we do not change this approach to conservation in Africa, we will lose all of our wildlife and with it, a part of our humanity. I believe that the time for Africans to define conservation ourselves has come.

(Applause)

And when Africa leads its own conservation efforts, we will not only restore our wildlife populations but our land and our cultures and our broken relationship with nature. Through my work with Ewaso Lions, an organization based in northern Kenya doing lion conservation, I am working with a group of people who, together we are co-designing what that conservation could look like.

But first, a little about myself. I grew up in a crumbling bungalow in the heart of Nairobi, Kenya's capital city. Long before it was called Nairobi by the Maasai, the nomadic pastoralists where I get my heritage, they had called it a different name. Nakusontelon. "The beginning of all beauty." As they would graze their cows and goats on the banks of the river, they would watch the evening sun creep down the acacia trees. That was their vision of beauty. Centuries later, I would do the same, I would watch the monkeys in the giant trees, and colorful birds would call to each other in the morning. In October, when the nandi flame trees would drop the last of their fiery orangy flowers that we would use for hopscotch in school, there would be thousands and thousands of jacaranda trees in full bloom across the city, reminding us that it was the start of exam season. (Laughter) "Have you studied? Are you ready?" they seemed to say. We were just a part of nature. It was just a fact.

And then the chainsaws came. They cut down so much of what I loved, they cut down my memories. And they have kept coming not just to my city, but to places around the world, and not just for trees, but for everything. Let me put some numbers here so you understand what I mean. Lions have lost 92 percent of the area that they used to roam in Africa. Out of a possible 100,000 lions maybe just a century ago, there are now only about 20,000 lions left in Africa. And in Kenya, there are only 2,500 lions left or thereabouts.

So what do you do when you're confronted with such loss? The answer for me was to study. And so at the University of Nairobi, equipped with new zoological expertise, I was informed that I could go out and teach local people how to live alongside wildlife. Where did that thinking come from, that I could go out and teach people how to live? At the University of Oxford, I took my studies further, and I really began to unearth the conservation models that had led us to this point. And while my studies have provided a frame with which to view what was happening, it is really on the ground in my country doing the work that I have gained the most perspective and clarity. In the Samburu region of northern Kenya, there's still little separation between people and wildlife and livestock. Here, you can still hear the cow bells clanging as a little boy brings his goats to water on the mighty Ewaso Ng’iro river. And behind him, nibbling on the tops of trees, are giraffes. And behind that, the rumble of elephants. It is here that I have found a group of people who are pushing back on that narrative that excludes us and tells us that we're not fit to lead and really building true community-led conservation.

There is so much to this approach that I believe could be important to form the new Kenyan and the new African conservation. So let me share some of those things. First, out with parachute conservation and in with indigenous local leadership.

(Applause)

Parachute conservation might be a new term for some, but it's just that old superhero story. You jet in, you have all the answers, you employ a few people to effect your solutions, and then you leave or you never hand over. And the world labels you a hero. This sort of conservation is so detrimental because it means that local people will forever be the helpers or the local informants and never the leaders and the decision makers. And when that happens, people lose. And when people lose, wildlife loses. So what's a better way? Let me give you an example.

One of the first people to join the Ewaso Lions project was Jeneria Lekilelei, a young Samburu warrior at the time, and now a junior elder. Now this is not some crazy thing you wouldn't understand. A Samburu warrior is just a young man between the ages of 15 and 30 or thereabouts, and it is his job to take care of the family's livestock. The Samburu and the Maasai are brother tribes. But while I have lost quite a lot of my Maasai heritage to city life, Jeneria still lives a very traditional Samburu life. And so while I was at home, watching David Attenborough and loving lions, Jeneria was hating lions. He saw them as the killers of his cows, and it's understandable that when a lion comes along and takes the family cow or the family camel, there’s going to be anger, and people will go out and kill lions. But Jeneria had an idea. He wanted to involve warriors like himself in conservation. He knew that these warriors had the exact skills to track and kill lions every time they'd go after livestock. He also knew that these warriors had never been brought to the decision-making table. And so he brought them, and he said, "Instead of us tracking lions to kill them, let us track lions and then tell every other herder where these lions are, so that livestock are safe and lions are safe. And they can share the space.” And it is through Jeneria's Warrior Watch program that he has worked with these warriors as conservation leaders, and they have saved lions hundreds of times in this way. And Jeneria, as the director of community conservation, has worked with his community over these years, and the Samburu lion population has tripled.

(Applause)

Next, let us stop merely involving women. Women must be as much part of the solution as men. And if our imagination for 50 percent of the world’s human population ends at involvement, we have already lost. So women where I work demanded to be part of conservation. They said --

(Applause)

They did this, not just because they saw the men, but because they have a historical stake in the game. In the Samburu creation story, wildlife belong to women. So the story goes that all the animals in the world at the beginning of time belong to the Samburu, and they were all livestock. The men were apparently very good livestock keepers, whereas the women were terrible and irresponsible, and they let the livestock out of the enclosure. And donkeys became zebras, and camels became giraffes. And that's how the wildlife of the world came to be. So these women took this myth and they said, "We are turning this patriarchal myth on its head. We are the people who own the wildlife, and so you're doing wildlife conservation? Then that's our business." And one of them who said this was Munteli, who is the coordinator of the Mother of Lions program. The Mama Simba program. So Munteli said that as part of their work providing lion locations and forming a home network, that all the women, including herself, need to be taught to read and write. And so they were attending class once a week. And then Munteli came back and said, "Actually, you know, we have far overtaken the men. So we have built an enclosure in our village. Bring your teacher and bring your whiteboard. We want lessons four times a week." And so the women were learning.

And then Munteli came back and said, "You people are not letting me do my work, I need to reach women in so many other villages."

And so we asked her, "Munteli, what would you like?"

And she said, "Teach me how to drive."

Munteli is now one of the first traditional Samburu women to drive a car.

(Applause)

In her region. And she, after just learning how to read and write just a few years ago, she texts lion locations in three different languages. She has proved that the impossible is now possible. She has expanded the room for women to participate in conservation, and there is room for all of them.

Conservation is about people. I have learned that the people who are keeping lions roaming in Kenya today are warriors and women and children and elders. They are people educated by their culture; they are urbanites with a respect for that culture. And as more Africans allow co-existence to happen in our spaces, we will turn back the clock on wildlife declines and really make life better for all of us. It is time for conservation to be broad. Broad enough not just to include a species in trouble, but our land and our cultures, our innovation, our story, us. Who we were, who we are and who we want to be.

Thank you.

(Applause)