Do you remember this one?

(Laughter)

It's a Nokia 3310. Once recognized as the greatest phone ever produced. I guess most of you in this room owned one, didn't you? Please raise your hand if you owned a 3310. Wow, so almost 100 percent market share here.

(Laughter)

So you'll remember that it never ran out of battery.

(Laughter)

You could play Snake on it.

(Laughter)

It was world-famous for being the indestructible phone. So in the mobile industry, the saying used to go that if someone drops an iPhone, the screen breaks. If someone drops a Nokia 3310, the floor breaks. It was unbelievably solid.

The 3310 embodied exactly what Nokia stood for as a brand: resilience, quality and innovation. It was products like this one that turned Nokia into one of the most successful companies on the planet.

But as you will also remember, there is another and a more tragic side to this story. Because today, the 3310 rests in peace at the gadget's graveyard. It's become a symbol of the collapse of Nokia, a company that went from 50 percent global market share to three percent in less than five years. And it made me think that, while we talk a lot about how an organization achieves success, maybe we don't talk enough about the psychological challenges that often follow success.

Because if you think about it, almost every industry has its own Nokia story. Companies that once dominated their industry but then somehow completely lost the mojo. They all leave us with that million dollar question. Why do successful companies actually fail? And what could they have done to stay ahead of the pack?

So I'm going to try and answer that question today, not by using traditional management thinking but by using an idea from football analytics, which I believe explains why many successful companies so often hesitate to change until it's too late.

Before I start, I need to ask a very important question. Do we have any Newcastle United supporters in the room?

Audience: Yeah!

RA: Yeah, there’s a couple there. So, guys, I'm just going to warn you, the next 10 minutes will be painful. I know the last 25 years have been painful, but don't take this personally. This is the stadium of Newcastle United, St James' Park. Every other week, 50,000 die-hard supporters flock to the stadium to watch their team play. And instinctively, Newcastle United has all the building blocks to become a really successful football club. They got a billionaire businessman owner, they got a fan base most other clubs would die for. But despite all that, Newcastle is also known as the team that never really fulfilled its potential. But then a little bit more than five years ago, in 2012, the fortune seems to change for Newcastle because they sensationally finished fifth in the English Premier League, the strongest league in the world. That was an amazing achievement. All the experts predicted Newcastle to be battling [to] avoid relegation. Now they were fifth. Inside Newcastle, the excitement was bubbling too. The management team was convinced this is the start of a new era in the football club's history. So they decided to reward the head coach and his whole coaching staff a historic-long, unbreakable eight-year contract. And they really tried to do everything they could to keep the squad together for the following season, because that's how successful organizations are supposed to think, right?

The following season this happened. Newcastle almost relegated. They finished 16th, and no one had a clue what was going on. Because they had the same players, they had the same coaching staff, they even played in the same stadiums. I mean, nothing's changed. How could a largely unchanged team go from fifth to 16th in less than 12 months?

I'm going to try and answer that question. But first, I’m going to give you a little bit of background. Because in football, there’s a good old expression that's frequently used by coaches, players, commentators, experts. It goes like this: the league table never lies. It kind of assumes that once the last game of a season is played, justice prevails. The team that finishes top of the table is the best-performing team, and the teams that relegate are the worst-performing teams. At the end of the day, everyone gets what they deserve.

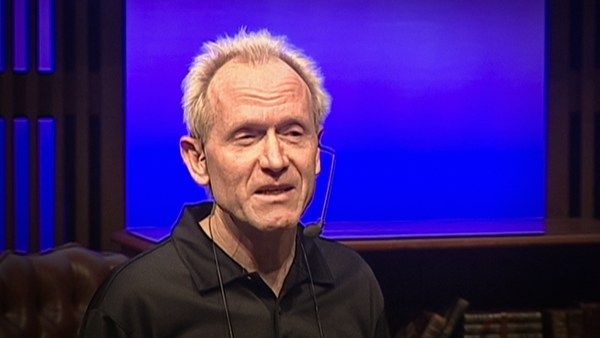

It's not that simple, actually. And let me explain why. Please meet Matthew Benham. He's a gambler. He convinced me the brightest guys in football don't work for the football clubs. They work in the gambling industry. And I’m not talking about the amateur gambler, the guy that is placing a bet every Saturday morning to trigger his weekly rush of adrenaline. I'm talking about the pros, the guys that are using sophisticated mathematical models to place the bets. That's the brightest guys, and Matthew is one of them. He's an Oxford graduate in physics that decided to set up his own betting syndicate in North London, basically an office full of PhD statisticians calculating the probabilities for the outcome of football games. That has made him a rich man. So rich, he decided to buy the football club he supported since he was a teenager: Brentford in West London.

And that's where I met him five years ago, at Jersey Road, the training ground of Brentford. At the time we met, Brentford was third in League One, which is the third tier of English football. There was only five games remaining of the season, and Brentford was pushing for a promotion. So I said to Matthew, "What do you think? Are you going to promote this season and what does your gut feel say?"

He gave me an answer I didn't quite expect. It was not an answer full of excitement. The guy just looked at me and then he said, very dry, “Well, at the moment there’s a 42 percent chance we’ll promote.”

That comment made me realize that I met someone who thought completely different about the game than I ever met before. Over the next couple of months, Matthew and I started to meet regularly to exchange ideas about how you could run a football club differently. In particular, how would it be possible to break the correlation between spending and results that seems to exist? Is it possible to not outspend but outthink the competition by using the weapons of a gambler, data and analytics?

One day we had lunch at a restaurant together in Soho in London, and Matthew said to me he'd been looking to buy another football club. And I immediately responded, "Why don't you take a look at the club I supported when I was a teenager," FC Midtjylland, based in the western rural Denmark, in the middle of nowhere. Midtjylland was almost broke at the time, so it was a perfect place to start testing radical ideas. A week later, we flew to Denmark, and we had a look at the club.

Eventually, he decided to buy the club. He made me the chairman of the club, and we've run the club together for the past four years. In the first season, we won the first championship in the club’s history, and a year later we became world-famous because we beat the mighty Manchester United in the Europa League. Unfortunately, in the UK, that's more perceived as the absolute embarrassment of Manchester United than the genius of Midtjylland, but we will live with that.

(Laughter)

Suddenly, media, newspapers, TV stations from all the world were flying to western Denmark to learn more about this little club no one can pronounce the name of, which is run by an English gambler using data and analytics to find a competitive edge.

So here's the thing. If you want to understand how a gambler thinks, there’s one concept you must get, it’s this: the league table always lies.

Why is a gambler saying that? Because he understands football is a very random game. It's a much more random game than basketball, for example. Why is that? Because football is a low-scoring sport. There's not a lot of goals in football. No, the average number of goals in a football game is 2.8. The average number of goals in a basketball games is above 200. Here's the principle. The fewer goals there is in a sport, the more impact random events have. Random events like the ball getting deflected and spins into the net, or the referee making a wrong call in the last minute of the game. Ultimately, this means that the best team wins less often in football, a low scoring-sport, than in a high-scoring sport like basketball. And that's why the league table lies. It lies more after ten games than after 20 games. But even 38 games, that is a full season, 38 games is a very small sample size. You know, not enough to strip out the randomness from the equation.

So a gambler is in the business of making predictions and backing those predictions with his bets. And when he decides to back a team and place a bet, he doesn't look at where that team is in the league table. He looks at underlying performance indicators that have more predictive value, tells him more about where that team is likely to go in the future than its current league table position.

So let's go back to Newcastle's glory season when they finished fifth and revisit that through the lens of a gambler. Because whereas experts in the game were overly impressed by Newcastle's performance, the gamblers were very skeptical. Their analysis showed that this was a fragile bubble that could burst any time. Here's why. One of the statistics a gambler trusts a lot is the statistic called goal difference. It's the difference between the number of goals a team scores versus the number of goals the opponent scores. It's a very reliable indicator for a team's strength.

So let's look at that. Newcastle finished fifth with a total shot differential of plus-five. A long way behind the four top teams. And if you look at that column, it's by far the lowest number. This indicates what a gambler calls an extremely effective goal distribution All goes in football are important. Not all goals are equally important. So here's an example. Let's say Newcastle scores two goals over two games and the opponent scores six goals. Newcastle will be better off winning 1-0 in the first game, losing 6-1 in the second, rather than losing twice 3-1. Same goal difference but different number of points. So if a team is able to produce, concede a number of goals throughout the season, how effective those scores follow the goal distribution, there's a big degree of randomness to that. And if you break down Newcastle's 65 points this season, you’ll see that it was driven by a very effective goal distribution: eight wins with one goal and three major losses with more than three goals. It's very unlikely statistically to be able to repeat 65 points with a plus five goal difference.

Another statistic a gambler trusts is something called shot differential: the difference between the number of shots a team produces versus the number of shots the opponent produces. It's statistically very well-documented in football that the best team over time produces more shots than the worst teams. So let's have a look at that. And as you can see, Newcastle finished fifth with a total shot differential of -1.4. Clearly they don't belong in this company. This indicates unsustainably high conversion rate. When you have a positive goal difference driven by a negative shot differential, it indicates unsustainably high conversion rates. How many of those shots were converted to goals? And Newcastle had especially one player this season who stood out, Cisse, their top scorer. A key component of their success. He converted 33 percent of his shots. Ladies and gentlemen, that's a freaky number. Here is how I would put it. Newcastle's fifth place is the equivalent of a publicly traded company having a very high share price and a very low customer satisfaction at the same time. You can have that for one year, but you can't maintain that over time.

Here's a visualization of how a gambler perceived the situation. The black line shows the number of points Newcastle achieved throughout those two seasons when they were fifth and when there were 16th. The red line is the underlying performance, what a gambler calls expected points. So as you can see, Newcastle got a lot more points in the first season when they finished fifth, than the underlying performance justified. Actually, Newcastle performed almost the same way in those two seasons. They just got less lucky.

And this reframes the original question. Because why did Newcastle’s management team not see this downturn coming? Why did they decide to reward the head coach with a historic, long, unbreakable contract when the results were clearly unsustainable? I believe that Newcastle was blinded by one the most common management delusions, what psychologists call outcome bias. The assumption that good results are always the consequence of good decisions and superior performance. Or, let’s put it in another way: success turns luck into genius. And this is where the message becomes about much more than just football analytics, right? Because when an organization fails, it becomes very natural for us to dig for reasons, to ask the tough questions. Why did we fail? How can we do things better? But when we are successful, we don't ask those questions. We tend to just cruise on blinded by outcome bias. We expect results to continue automatically. We don’t dig into them and ask, “What was actually the underlying reason for the success?” Was it because of the oil price? Was it because of good leadership or because of exceptional market conditions? How many companies do you think confuse good leadership with good market conditions?

Here's the thing. Successful organizations should think more like a good gambler. Because a good gambler has trained his brain to resist the human tendency to assume that good outcomes always mean that someone acted brilliantly. A good gambler treats success with the same skepticism as he treats failure. And this is what successful organizations should do too, if they want to stay relevant: ask themselves the questions of a gambler. Why were we actually successful? How do we separate luck from skill? Is it possible that our league table sometimes lied too?

Thank you very much.