Everyone is both a learner and a teacher. This is me being inspired by my first tutor, my mom, and this is me teaching Introduction to Artificial Intelligence to 200 students at Stanford University.

Now the students and I enjoyed the class, but it occurred to me that while the subject matter of the class is advanced and modern, the teaching technology isn't. In fact, I use basically the same technology as this 14th-century classroom. Note the textbook, the sage on the stage, and the sleeping guy in the back. (Laughter) Just like today.

So my co-teacher, Sebastian Thrun, and I thought, there must be a better way. We challenged ourselves to create an online class that would be equal or better in quality to our Stanford class, but to bring it to anyone in the world for free.

We announced the class on July 29th, and within two weeks, 50,000 people had signed up for it. And that grew to 160,000 students from 209 countries. We were thrilled to have that kind of audience, and just a bit terrified that we hadn't finished preparing the class yet. (Laughter)

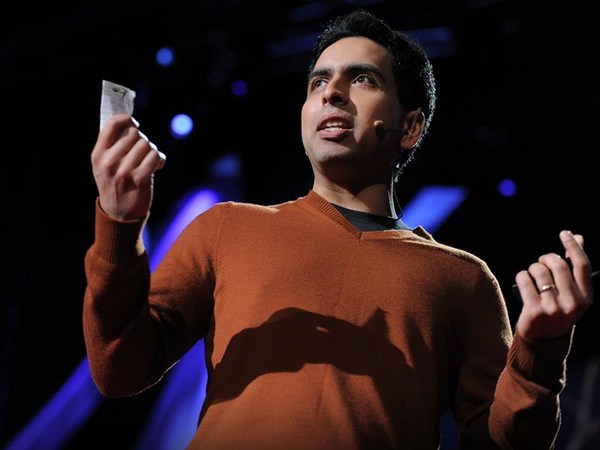

So we got to work. We studied what others had done, what we could copy and what we could change. Benjamin Bloom had showed that one-on-one tutoring works best, so that's what we tried to emulate, like with me and my mom, even though we knew it would be one-on-thousands. Here, an overhead video camera is recording me as I'm talking and drawing on a piece of paper.

A student said, "This class felt like sitting in a bar with a really smart friend who's explaining something you haven't grasped, but are about to." And that's exactly what we were aiming for.

Now, from Khan Academy, we saw that short 10-minute videos worked much better than trying to record an hour-long lecture and put it on the small-format screen. We decided to go even shorter and more interactive. Our typical video is two minutes, sometimes shorter, never more than six, and then we pause for a quiz question, to make it feel like one-on-one tutoring. Here, I'm explaining how a computer uses the grammar of English to parse sentences, and here, there's a pause and the student has to reflect, understand what's going on and check the right boxes before they can continue.

Students learn best when they're actively practicing. We wanted to engage them, to have them grapple with ambiguity and guide them to synthesize the key ideas themselves. We mostly avoid questions like, "Here's a formula, now tell me the value of Y when X is equal to two." We preferred open-ended questions.

One student wrote, "Now I'm seeing Bayes networks and examples of game theory everywhere I look." And I like that kind of response. That's just what we were going for. We didn't want students to memorize the formulas; we wanted to change the way they looked at the world. And we succeeded. Or, I should say, the students succeeded.

And it's a little bit ironic that we set about to disrupt traditional education, and in doing so, we ended up making our online class much more like a traditional college class than other online classes. Most online classes, the videos are always available. You can watch them any time you want. But if you can do it any time, that means you can do it tomorrow, and if you can do it tomorrow, well, you may not ever get around to it. (Laughter)

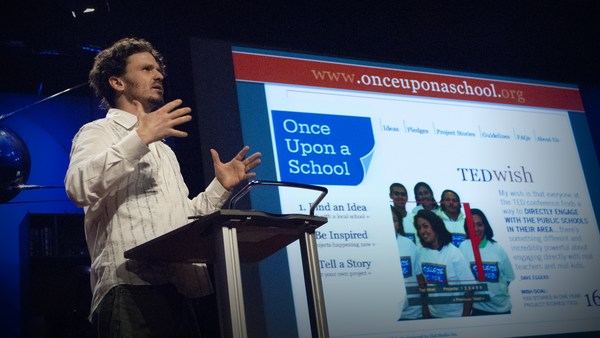

So we brought back the innovation of having due dates. (Laughter) You could watch the videos any time you wanted during the week, but at the end of the week, you had to get the homework done. This motivated the students to keep going, and it also meant that everybody was working on the same thing at the same time, so if you went into a discussion forum, you could get an answer from a peer within minutes. Now, I'll show you some of the forums, most of which were self-organized by the students themselves.

From Daphne Koller and Andrew Ng, we learned the concept of "flipping" the classroom. Students watched the videos on their own, and then they come together to discuss them. From Eric Mazur, I learned about peer instruction, that peers can be the best teachers, because they're the ones that remember what it's like to not understand. Sebastian and I have forgotten some of that. Of course, we couldn't have a classroom discussion with tens of thousands of students, so we encouraged and nurtured these online forums.

And finally, from Teach For America, I learned that a class is not primarily about information. More important is motivation and determination. It was crucial that the students see that we're working hard for them and they're all supporting each other.

Now, the class ran 10 weeks, and in the end, about half of the 160,000 students watched at least one video each week, and over 20,000 finished all the homework, putting in 50 to 100 hours. They got this statement of accomplishment.

So what have we learned? Well, we tried some old ideas and some new and put them together, but there are more ideas to try. Sebastian's teaching another class now. I'll do one in the fall. Stanford Coursera, Udacity, MITx and others have more classes coming. It's a really exciting time.

But to me, the most exciting part of it is the data that we're gathering. We're gathering thousands of interactions per student per class, billions of interactions altogether, and now we can start analyzing that, and when we learn from that, do experimentations, that's when the real revolution will come. And you'll be able to see the results from a new generation of amazing students. (Applause)