So, people argue vigorously about the definition of life. They ask if it should have reproduction in it, or metabolism, or evolution. And I don't know the answer to that, so I'm not going to tell you. I will say that life involves computation. So this is a computer program. Booted up in a cell, the program would execute, and it could result in this person; or with a small change, it could result in this person; or another small change, this person; or with a larger change, this dog, or this tree, or this whale.

So now, if you take this metaphor [of] genome as program seriously, you have to consider that Chris Anderson is a computer-fabricated artifact, as is Jim Watson, Craig Venter, as are all of us. And in convincing yourself that this metaphor is true, there are lots of similarities between genetic programs and computer programs that could help to convince you. But one, to me, that's most compelling is the peculiar sensitivity to small changes that can make large changes in biological development -- the output. A small mutation can take a two-wing fly and make it a four-wing fly. Or it could take a fly and put legs where its antennae should be. Or if you're familiar with "The Princess Bride," it could create a six-fingered man.

Now, a hallmark of computer programs is just this kind of sensitivity to small changes. If your bank account's one dollar, and you flip a single bit, you could end up with a thousand dollars. So these small changes are things that I think that -- they indicate to us that a complicated computation in development is underlying these amplified, large changes.

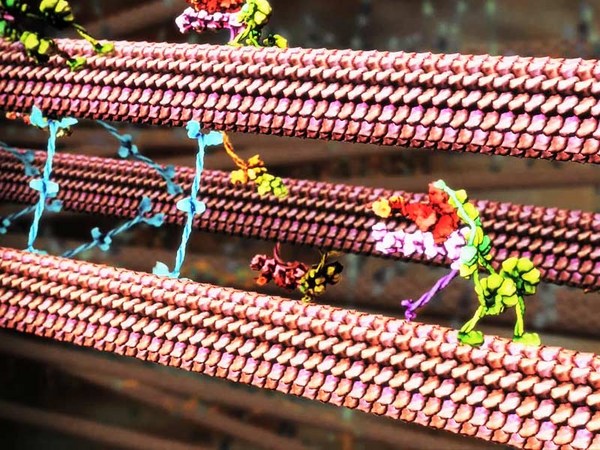

So now, all of this indicates that there are molecular programs underlying biology, and it shows the power of molecular programs -- biology does. And what I want to do is write molecular programs, potentially to build technology. And there are a lot of people doing this, a lot of synthetic biologists doing this, like Craig Venter. And they concentrate on using cells. They're cell-oriented. So my friends, molecular programmers, and I have a sort of biomolecule-centric approach. We're interested in using DNA, RNA and protein, and building new languages for building things from the bottom up, using biomolecules, potentially having nothing to do with biology. So, these are all the machines in a cell. There's a camera. There's the solar panels of the cell, some switches that turn your genes on and off, the girders of the cell, motors that move your muscles. My little group of molecular programmers are trying to refashion all of these parts from DNA. We're not DNA zealots, but DNA is the cheapest, easiest to understand and easy to program material to do this. And as other things become easier to use -- maybe protein -- we'll work with those.

If we succeed, what will molecular programming look like? You're going to sit in front of your computer. You're going to design something like a cell phone, and in a high-level language, you'll describe that cell phone. Then you're going to have a compiler that's going to take that description and it's going to turn it into actual molecules that can be sent to a synthesizer and that synthesizer will pack those molecules into a seed. And what happens if you water and feed that seed appropriately, is it will do a developmental computation, a molecular computation, and it'll build an electronic computer. And if I haven't revealed my prejudices already, I think that life has been about molecular computers building electrochemical computers, building electronic computers, which together with electrochemical computers will build new molecular computers, which will build new electronic computers, and so forth.

And if you buy all of this, and you think life is about computation, as I do, then you look at big questions through the eyes of a computer scientist. So one big question is, how does a baby know when to stop growing? And for molecular programming, the question is how does your cell phone know when to stop growing? (Laughter) Or how does a computer program know when to stop running? Or more to the point, how do you know if a program will ever stop? There are other questions like this, too. One of them is Craig Venter's question. Turns out I think he's actually a computer scientist. He asked, how big is the minimal genome that will give me a functioning microorganism? How few genes can I use? This is exactly analogous to the question, what's the smallest program I can write that will act exactly like Microsoft Word? (Laughter) And just as he's writing, you know, bacteria that will be smaller, he's writing genomes that will work, we could write smaller programs that would do what Microsoft Word does.

But for molecular programming, our question is, how many molecules do we need to put in that seed to get a cell phone? What's the smallest number we can get away with? Now, these are big questions in computer science. These are all complexity questions, and computer science tells us that these are very hard questions. Almost -- many of them are impossible. But for some tasks, we can start to answer them. So, I'm going to start asking those questions for the DNA structures I'm going to talk about next. So, this is normal DNA, what you think of as normal DNA. It's double-stranded, it's a double helix, has the As, Ts, Cs and Gs that pair to hold the strands together. And I'm going to draw it like this sometimes, just so I don't scare you. We want to look at individual strands and not think about the double helix. When we synthesize it, it comes single-stranded, so we can take the blue strand in one tube and make an orange strand in the other tube, and they're floppy when they're single-stranded. You mix them together and they make a rigid double helix. Now for the last 25 years, Ned Seeman and a bunch of his descendants have worked very hard and made beautiful three-dimensional structures using this kind of reaction of DNA strands coming together. But a lot of their approaches, though elegant, take a long time. They can take a couple of years, or it can be difficult to design.

So I came up with a new method a couple of years ago I call DNA origami that's so easy you could do it at home in your kitchen and design the stuff on a laptop. But to do it, you need a long, single strand of DNA, which is technically very difficult to get. So, you can go to a natural source. You can look in this computer-fabricated artifact, and he's got a double-stranded genome -- that's no good. You look in his intestines. There are billions of bacteria. They're no good either. Double strand again, but inside them, they're infected with a virus that has a nice, long, single-stranded genome that we can fold like a piece of paper. And here's how we do it.

This is part of that genome. We add a bunch of short, synthetic DNAs that I call staples. Each one has a left half that binds the long strand in one place, and a right half that binds it in a different place, and brings the long strand together like this. The net action of many of these on that long strand is to fold it into something like a rectangle.

Now, we can't actually take a movie of this process, but Shawn Douglas at Harvard has made a nice visualization for us that begins with a long strand and has some short strands in it. And what happens is that we mix these strands together. We heat them up, we add a little bit of salt, we heat them up to almost boiling and cool them down, and as we cool them down, the short strands bind the long strands and start to form structure. And you can see a little bit of double helix forming there. When you look at DNA origami, you can see that what it really is, even though you think it's complicated, is a bunch of double helices that are parallel to each other, and they're held together by places where short strands go along one helix and then jump to another one. So there's a strand that goes like this, goes along one helix and binds -- it jumps to another helix and comes back. That holds the long strand like this.

Now, to show that we could make any shape or pattern that we wanted, I tried to make this shape. I wanted to fold DNA into something that goes up over the eye, down the nose, up the nose, around the forehead, back down and end in a little loop like this. And so, I thought, if this could work, anything could work. So I had the computer program design the short staples to do this. I ordered them; they came by FedEx. I mixed them up, heated them, cooled them down, and I got 50 billion little smiley faces floating around in a single drop of water. And each one of these is just one-thousandth the width of a human hair, OK?

So, they're all floating around in solution, and to look at them, you have to get them on a surface where they stick. So, you pour them out onto a surface and they start to stick to that surface, and we take a picture using an atomic-force microscope. It's got a needle, like a record needle, that goes back and forth over the surface, bumps up and down, and feels the height of the first surface. It feels the DNA origami. There's the atomic-force microscope working and you can see that the landing's a little rough. When you zoom in, they've got, you know, weak jaws that flip over their heads and some of their noses get punched out, but it's pretty good. You can zoom in and even see the extra little loop, this little nano-goatee.

Now, what's great about this is anybody can do this. And so, I got this in the mail about a year after I did this, unsolicited. Anyone know what this is? What is it? It's China, right? So, what happened is, a graduate student in China, Lulu Qian, did a great job. She wrote all her own software to design and built this DNA origami, a beautiful rendition of China, which even has Taiwan, and you can see it's sort of on the world's shortest leash, right? (Laughter) So, this works really well and you can make patterns as well as shapes, OK? And you can make a map of the Americas and spell DNA with DNA.

And what's really neat about it -- well, actually, this all looks like nano-artwork, but it turns out that nano-artwork is just what you need to make nano-circuits. So, you can put circuit components on the staples, like a light bulb and a light switch. Let the thing assemble, and you'll get some kind of a circuit. And then you can maybe wash the DNA away and have the circuit left over. So, this is what some colleagues of mine at Caltech did. They took a DNA origami, organized some carbon nano-tubes, made a little switch, you see here, wired it up, tested it and showed that it is indeed a switch. Now, this is just a single switch and you need half a billion for a computer, so we have a long way to go. But this is very promising because the origami can organize parts just one-tenth the size of those in a normal computer. So it's very promising for making small computers.

Now, I want to get back to that compiler. The DNA origami is a proof that that compiler actually works. So, you start with something in the computer. You get a high-level description of the computer program, a high-level description of the origami. You can compile it to molecules, send it to a synthesizer, and it actually works. And it turns out that a company has made a nice program that's much better than my code, which was kind of ugly, and will allow us to do this in a nice, visual, computer-aided design way.

So, now you can say, all right, why isn't DNA origami the end of the story? You have your molecular compiler, you can do whatever you want. The fact is that it does not scale. So if you want to build a human from DNA origami, the problem is, you need a long strand that's 10 trillion trillion bases long. That's three light years' worth of DNA, so we're not going to do this. We're going to turn to another technology, called algorithmic self-assembly of tiles. It was started by Erik Winfree, and what it does, it has tiles that are a hundredth the size of a DNA origami. You zoom in, there are just four DNA strands and they have little single-stranded bits on them that can bind to other tiles, if they match. And we like to draw these tiles as little squares. And if you look at their sticky ends, these little DNA bits, you can see that they actually form a checkerboard pattern. So, these tiles would make a complicated, self-assembling checkerboard. And the point of this, if you didn't catch that, is that tiles are a kind of molecular program and they can output patterns. And a really amazing part of this is that any computer program can be translated into one of these tile programs -- specifically, counting. So, you can come up with a set of tiles that when they come together, form a little binary counter rather than a checkerboard. So you can read off binary numbers five, six and seven.

And in order to get these kinds of computations started right, you need some kind of input, a kind of seed. You can use DNA origami for that. You can encode the number 32 in the right-hand side of a DNA origami, and when you add those tiles that count, they will start to count -- they will read that 32 and they'll stop at 32. So, what we've done is we've figured out a way to have a molecular program know when to stop going. It knows when to stop growing because it can count. It knows how big it is. So, that answers that sort of first question I was talking about. It doesn't tell us how babies do it, however.

So now, we can use this counting to try and get at much bigger things than DNA origami could otherwise. Here's the DNA origami, and what we can do is we can write 32 on both edges of the DNA origami, and we can now use our watering can and water with tiles, and we can start growing tiles off of that and create a square. The counter serves as a template to fill in a square in the middle of this thing. So, what we've done is we've succeeded in making something much bigger than a DNA origami by combining DNA origami with tiles. And the neat thing about it is, is that it's also reprogrammable. You can just change a couple of the DNA strands in this binary representation and you'll get 96 rather than 32. And if you do that, the origami's the same size, but the resulting square that you get is three times bigger.

So, this sort of recapitulates what I was telling you about development. You have a very sensitive computer program where small changes -- single, tiny, little mutations -- can take something that made one size square and make something very much bigger. Now, this -- using counting to compute and build these kinds of things by this kind of developmental process is something that also has bearing on Craig Venter's question. So, you can ask, how many DNA strands are required to build a square of a given size? If we wanted to make a square of size 10, 100 or 1,000, if we used DNA origami alone, we would require a number of DNA strands that's the square of the size of that square; so we'd need 100, 10,000 or a million DNA strands. That's really not affordable. But if we use a little computation -- we use origami, plus some tiles that count -- then we can get away with using 100, 200 or 300 DNA strands. And so we can exponentially reduce the number of DNA strands we use, if we use counting, if we use a little bit of computation. And so computation is some very powerful way to reduce the number of molecules you need to build something, to reduce the size of the genome that you're building.

And finally, I'm going to get back to that sort of crazy idea about computers building computers. If you look at the square that you build with the origami and some counters growing off it, the pattern that it has is exactly the pattern that you need to make a memory. So if you affix some wires and switches to those tiles -- rather than to the staple strands, you affix them to the tiles -- then they'll self-assemble the somewhat complicated circuits, the demultiplexer circuits, that you need to address this memory. So you can actually make a complicated circuit using a little bit of computation. It's a molecular computer building an electronic computer. Now, you ask me, how far have we gotten down this path? Experimentally, this is what we've done in the last year. Here is a DNA origami rectangle, and here are some tiles growing from it. And you can see how they count. One, two, three, four, five, six, nine, 10, 11, 12, 17. So it's got some errors, but at least it counts up. (Laughter)

So, it turns out we actually had this idea nine years ago, and that's about the time constant for how long it takes to do these kinds of things, so I think we made a lot of progress. We've got ideas about how to fix these errors. And I think in the next five or 10 years, we'll make the kind of squares that I described and maybe even get to some of those self-assembled circuits.

So now, what do I want you to take away from this talk? I want you to remember that to create life's very diverse and complex forms, life uses computation to do that. And the computations that it uses, they're molecular computations, and in order to understand this and get a better handle on it, as Feynman said, you know, we need to build something to understand it. And so we are going to use molecules and refashion this thing, rebuild everything from the bottom up, using DNA in ways that nature never intended, using DNA origami, and DNA origami to seed this algorithmic self-assembly.

You know, so this is all very cool, but what I'd like you to take from the talk, hopefully from some of those big questions, is that this molecular programming isn't just about making gadgets. It's not just making about -- it's making self-assembled cell phones and circuits. What it's really about is taking computer science and looking at big questions in a new light, asking new versions of those big questions and trying to understand how biology can make such amazing things. Thank you. (Applause)