Do you spend more money on virtual fashion in video games than you do on physical clothes? About a third of all teenage gamers in America do. Do you think the government is actually run by a secret cabal of demon-worshiping perverts? About 50 million people do.

(Laughter)

These numbers sound crazy to you? It's because they are, but they're also a sign of things to come. The world feels like a pretty insane place right now. And if you spend any time on the internet at all, you can probably tell that people think it's going to get a lot worse. Now, that may be the case, but this feeling is why I believe that we're going to see a rise in social unrest in the coming decades, and that is going to come from a surprising place. Video games.

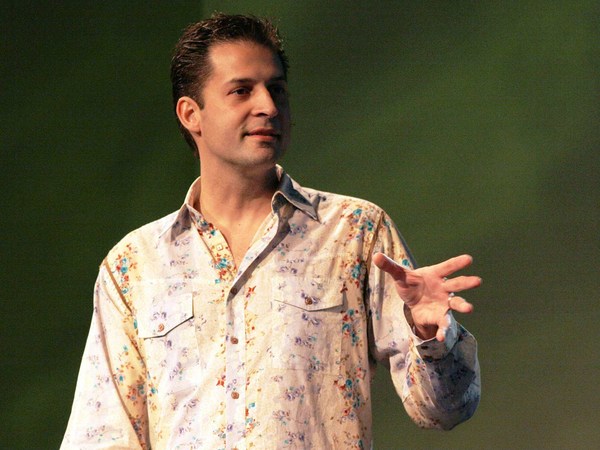

Now before you think, "Is this going to be another talk linking video game to violence?" Sorry to disappoint you, that’s been proven conclusively wrong, and that is really old thinking. But what I am going to argue is that video games are going to become the platform through which tomorrow's social battles will be fought and the source of recruitment for some of the strangest and possibly most impactful social movements of the future.

I like to call these video gamecults. Sounds kind of scary, I admit, but I hope to show how they might also be used as a tool to cause some serious hope.

Now this is all just my personal opinion. But I started thinking about this a few years ago after I heard a very interesting story while working in the Gulf. The story was about Hassan ibn Sabbah, a charismatic young preacher who lived about 1,000 years ago in an age full of drama, conflict and social change. Hassan became famous for creating the Order of Assassins: a fanatically devoted group of young men known as the fedayeen, "those who sacrifice themselves." His men were so devoted to him that, the legend goes, they would throw themselves from the rafters to their death at his command. Actually, this is where we get the expression "a leap of faith" from.

So this got me thinking. Why would someone do this? What could convince someone so fervently to believe in something that they would welcome their own death? The answer is 11th century virtual reality. See, Hassan had cultivated a myth that he could send people to heaven and bring them back again without actually having to die. And of course, he didn't actually have this power, but before a mission, the story goes, he would dose his soldiers with massive amounts of hash.

(Laughter) Their enemies actually called them the "ḥashshāshīn," which is also where we get the word "assassin" from. This would knock them out and then he would lower them down into a secret garden he had built behind his mountain fortress, designed to look exactly like a replica of heaven. Waking up in this simulated paradise, his men would gorge themselves on all the things they had been denied in life. Then, after a night of ecstasy, they would awaken back in their barracks, convinced of Hassan's powers, eager to fulfill his suicide missions in order to return to heaven again.

So. What does this have to do with today? Well, most scholars agree that this is probably just a myth, but that's not the point. The point is that people believed deeply in Hassan and his vision for the world and were willing to sacrifice their lives for it. He gave them a sense of meaning and purpose during a time of great uncertainty. A purpose which he communicated using the best tools of his day. And that is what brings us to video games.

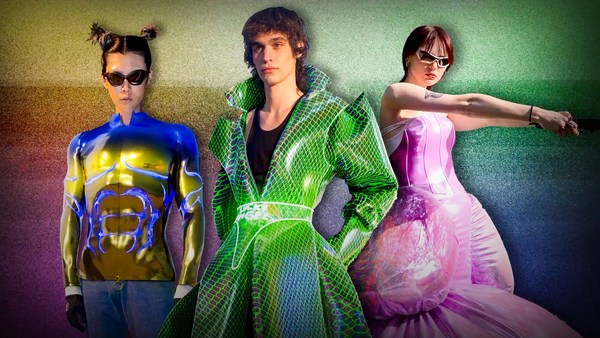

Video games are already the world's dominant form of entertainment. They're three times larger than the entire global film and music industries combined. Every year, the top streamers on Twitch receive on average twice as many views as the biggest Hollywood movies. And collectively, we spend twice as much time watching and playing video games as we do using all other forms of social media combined. That's a lot of eyeballs. Game sales are huge, but the real action is in in-game economies where people spend over 130 billion dollars a year buying and selling virtual goods online. Everything from outfits to avatars, to vehicles to weapons, to dances to architecture to music, to access to live events and more. Haven't even mentioned NFT or Web3, but these hopefully will become the infrastructure that drives this going forward. So if you're wondering what the metaverse looks like, this is it.

The reason games are so successful is because they provide a deep sense of engagement, community and purpose. Yes, we use them to escape and to entertain, and that’s OK. But at their best, they speak to some of our primal social and psychological needs, from feeling effective to achieving our goals, to belonging to a group, to working for something bigger than yourself. Describing his experience in a top World of Warcraft guild, the player Wincy once wrote, "It felt so amazing... Thinking back, it was probably the most intense, positive emotional experience of my life. Not my kid being born, not getting married."

(Laughter)

"My mind was convinced we were in a war against an insurmountable foe and we won."

You can probably see where I'm going with this. Although he later went on to regret the amount of time he spent online, gamers develop a deep sense of commitment to a shared narrative world. A world which provides for them in a way that "real-world" jobs and relationships often do not. And this is already the world that our children live in. The only thing that my son and daughter want for their birthdays are Skyblock coins and digital emotes for their characters. Most of their social time outside of school is spent hanging out in-game with their friends. My son Teo, he's already flipping NFTs to, in his words, get rich as quickly as possible so he can take care of us when the world falls apart. Thanks Teo, appreciate that.

That's why I think games are going to be one of the driving forces of tomorrow's culture. But if that's the game's part, what about the cults part? Well, I'm sure we can all agree that the coming years are going to be interesting, to say the least. From climate change, mass migration, pandemics, job loss and now war. The future feels terrifying for many people. And this is having a tremendous impact on our mental health. One third of all US undergraduates surveyed report having moderate to severe anxiety. Their rates of suicidal thinking and severe depression doubled over the last decade or so. And COVID didn't help. But it's not just the US, either. Two thirds of those surveyed in a study of 17 different countries reported that they thought their children were going to grow up poorer and not have successful careers. In other words, the world feels like it's falling apart for a lot of people. And when worlds fall apart, people start looking for answers wherever they can find them. And charismatic leaders like Hassan have always been happy to provide them. And their actions have shaped the course of history. From the Protestant Reformation in the 16th century to the rise of new religious movements in the 19th century, every era of social change historically has been followed by a wave of new believers and fanatical behavior. QAnon is just the most recent example. And while each generation's cults look different and the definition of a cult is certainly up for debate, they do share general characteristics. The first is that they inspire a sense of higher purpose, often through a lens of good versus evil, where you are the hero, that creates a sense of passion or commitment that seems insane or irrational to the outsider. And the second is that they adopt the form of and use the tools of the dominant organizations of their day. From the church to the corporation to the social media network to our subject for today, the metaverse.

So what happens when you mix billions of people looking for meaning, safety and security with widespread virtual worlds, crypto economies and gaming culture? The answer, I believe, is “gamecults.” Large-scale social movements powered by extreme or bizarre beliefs, birthed in virtual worlds, driven by game dynamics, but with real-world consequence.

The future is about to get weird. We can already see examples of this all around us. We just haven't had a name for it yet. Softer versions look like BTS stans swarming Donald Trump rallies online, but more extreme versions look like Hezbollah's own custom-made video game called Special Forces, designed to recruit young people and train them to kill their enemies. White nationalist groups are hosting Call of Duty tournaments online to attract followers, and there are Roblox games where you can drive your car through Black Lives Matter protesters or assume the role of Kyle Rittenhouse and shoot anti-fascist protesters. And there are many other examples, but all of them are wrapped in a layer of Discord servers and YouTube channels and podcasts that act as the funnel to draw you deeper into a web of extremism and radical behavior. What starts on the screen no longer stays on the screen. QAnon is a perfect example of this. What started on 4chan and Facebook, mutated into a live-action role-playing group for evangelical militants and ended up as an anti-vaccination campaign. Before you know it, we have a million excess deaths from COVID in the United States and a political landscape far stranger than anything we've ever seen. The same is going to be true for games. First you're a player, then you're a fan, soon you're in a clan, and before you know it, you're invading the Capitol.

So I'm a futurist. And there's a saying with futurists, that your job is not to just predict the automobile, but to predict the traffic jams. So what might this look like in 10 or 20 years, when widespread augmented and virtual reality meets thriving crypto economies and a generalized crisis of meaning? Well in the future, games are going to be everywhere. They're going to move from our screens and onto the streets around us. Hundreds of millions, if not billions of people will be buying, selling, making and trading virtual goods online. They're going to assume roles as characters, follow quests and get real-world money for in-game performance. Guilds, corporations and clans will form around them. They might start offering salaries, paying benefits, and providing real-world services like education or health care or even security. People's entire lives will be built around their characters and their stories, particularly if things get really bad. And those stories will come to dominate popular culture and politics.

Now, thankfully, not all of them will be harmful, but some will be violently evangelical in their nature. It's got me thinking, there must be a better way that we can use these dynamics to heal instead of harm. So I started thinking, what might this look like? How can we explore possible futures for positive gamecults? So here are just three examples I came up with a few friends. Consider Druidica, a Minecraft-like nature game designed to restore damaged ecosystems and preserve indigenous knowledge. Or perhaps Walkabout, a Rust-like survival game for refugees designed to encourage skill sharing, interdependence and mutual aid linked to scriptural messages of tolerance and compassion. Or perhaps Temple, a pray-to-earn game, linked to a network of nondenominational meditation spaces where players can perform coordinated acts of care to level up on the good works board. A kind of, decentralized church of kindness, powered maybe by HOLY coin.

It's clear that something like this is coming. The question is: What can we do about it now? As we've learned from social media, technological fixes and regulatory restrictions will only go so far. And in the attention economy of political priorities, gamecults are clearly quite low. But that’s OK, it means we still have time to do something about them. That's why I think that everyone, from policymakers to players to game designers and gamers should be having a conversation about what this means right now. If you are a media company, you should be talking to experts in radicalization. If you are a game company, you should be speaking to those who don't understand gaming dynamics and the communities around them. If you're a church or a religious institution, you should be understanding how people use these tools to build beliefs and what they're believing. And finally, perhaps most importantly, if you're a parent, you should be playing games with your kids to understand the world that they're growing up in and to have a conversation with them about the role that they might play in it.

Someone's going to connect these dots. The question is: Who is going to be our modern-day Hassan? And will the games of tomorrow be games of subjugation and domination? Or inspiration and liberation. It's really up to us.

Thank you.

(Applause)