Good morning everybody.

I work with really amazing, little, itty-bitty creatures called cells. And let me tell you what it's like to grow these cells in the lab. I work in a lab where we take cells out of their native environment. We plate them into dishes that we sometimes call petri dishes. And we feed them -- sterilely of course -- with what we call cell culture media -- which is like their food -- and we grow them in incubators.

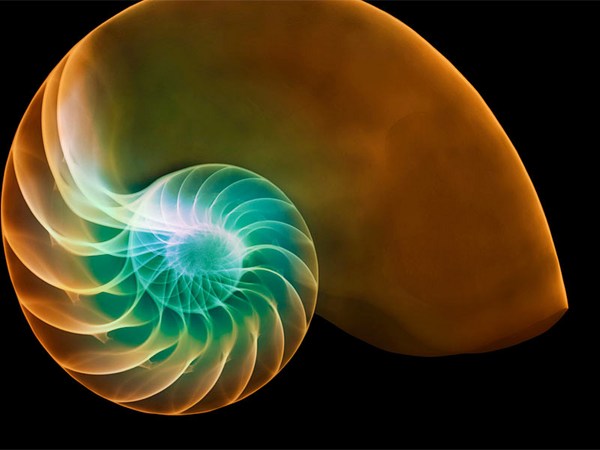

Why do I do this? We observe the cells in a plate, and they're just on the surface. But what we're really trying to do in my lab is to engineer tissues out of them. What does that even mean? Well it means growing an actual heart, let's say, or grow a piece of bone that can be put into the body. Not only that, but they can also be used for disease models. And for this purpose, traditional cell culture techniques just really aren't enough. The cells are kind of homesick; the dish doesn't feel like their home. And so we need to do better at copying their natural environment to get them to thrive. We call this the biomimetic paradigm -- copying nature in the lab.

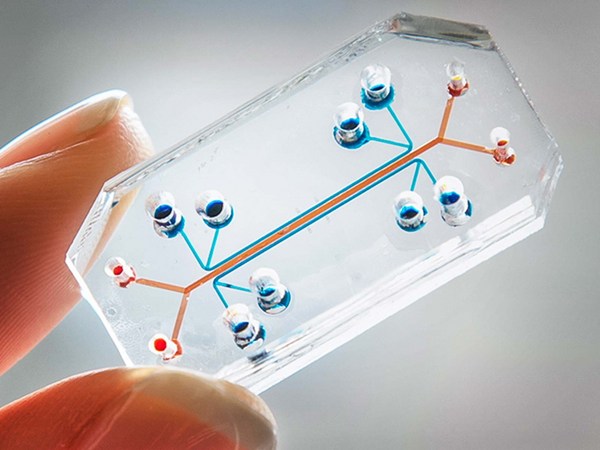

Let's take the example of the heart, the topic of a lot of my research. What makes the heart unique? Well, the heart beats, rhythmically, tirelessly, faithfully. We copy this in the lab by outfitting cell culture systems with electrodes. These electrodes act like mini pacemakers to get the cells to contract in the lab. What else do we know about the heart? Well, heart cells are pretty greedy. Nature feeds the heart cells in your body with a very, very dense blood supply. In the lab, we micro-pattern channels in the biomaterials on which we grow the cells, and this allows us to flow the cell culture media, the cells' food, through the scaffolds where we're growing the cells -- a lot like what you might expect from a capillary bed in the heart.

So this brings me to lesson number one: life can do a lot with very little. Let's take the example of electrical stimulation. Let's see how powerful just one of these essentials can be. On the left, we see a tiny piece of beating heart tissue that I engineered from rat cells in the lab. It's about the size of a mini marshmallow. And after one week, it's beating. You can see it in the upper left-hand corner. But don't worry if you can't see it so well. It's amazing that these cells beat at all. But what's really amazing is that the cells, when we electrically stimulate them, like with a pacemaker, that they beat so much more.

But that brings me to lesson number two: cells do all the work. In a sense, tissue engineers have a bit of an identity crisis here, because structural engineers build bridges and big things, computer engineers, computers, but what we are doing is actually building enabling technologies for the cells themselves. What does this mean for us? Let's do something really simple. Let's remind ourselves that cells are not an abstract concept. Let's remember that our cells sustain our lives in a very real way. "We are what we eat," could easily be described as, "We are what our cells eat." And in the case of the flora in our gut, these cells may not even be human. But it's also worth noting that cells also mediate our experience of life. Behind every sound, sight, touch, taste and smell is a corresponding set of cells that receive this information and interpret it for us. It begs the question: shall we expand our sense of environmental stewardship to include the ecosystem of our own bodies?

I invite you to talk about this with me further, and in the meantime, I wish you luck. May none of your non-cancer cells become endangered species.

Thank you.

(Applause)