I was only nine when my grandfather first described to me the horrors he witnessed six years earlier when human stampedes killed 39 people in our hometown of Nashik, India. It was during the 2003 Nashik Kumbh Mela, one of the world's largest religious gatherings. Every 12 years, over 30 million Hindu worshippers descend upon our city -- which is built only for 1.5 million people -- and stay for 45 days. The main purpose is to wash away all their sins by bathing in the river Godavari. And stampedes may easily happen because a high-density crowd moves at a slow pace. Apart from Nashik, this event happens in three other places in India, with varying frequency, and between 2001 and 2014, over 2,400 lives have been lost in stampedes at these events. What saddened me the most is seeing people around me resigning to the city's fate in witnessing the seemingly inevitable deaths of dozens at every Kumbh Mela.

I sought to change this, and I thought, why can't I try to find a solution to this? Because I knew it is wrong. Having learned coding at an early age and being a maker, I considered the wild idea --

(Laughter)

[Makers always find a way]

I considered the wild idea of building a system that would help regulate the flow of people and use it in the next Kumbh Mela in 2015, to have fewer stampedes and, hopefully, fewer deaths.

It seemed like a mission impossible, a dream too big, especially for a 15-year-old, yet that dream came true in 2015, when not only did we succeed in reducing the stampedes and their intensity, but we marked 2015 as the first Nashik Kumbh Mela to have zero stampedes.

(Applause)

It was the first time in recorded history that this event passed without any casualties.

How did we do it? It all started when I joined an innovation workshop by MIT Media Lab in 2014 called the Kumbhathon that aimed at solving challenges faced at the grand scale of Kumbh Mela.

Now, we figured out to solve the stampede problem, we wanted to know only three things: the number of people, the location, and the rate of the flow of people per minute. So we started to look for technologies that would help us get these three things. Can we distribute radio-frequency tokens to identify people? We figured out that it would be too expensive and impractical to distribute 30 million tags. Can you use CCTV cameras with image-processing techniques? Again, too expensive for that scale, along with the disadvantages of being non-portable and being completely useless in the case of rain, which is a common thing to happen in Kumbh Mela. Can we use cell phone tower data? It sounds like the perfect solution, but the funny part is, most of the people do not carry cell phones in events like Kumbh Mela. Also, the data wouldn't have been granular enough for us. So we wanted something that was real-time, low-cost, sturdy and waterproof, and it was easy to get the data for processing.

So we built Ashioto, meaning "footstep" in Japanese, as it consists of a portable mat which has pressure sensors which can count the number of people walking on it, and sends the data over the internet to the advanced data analysis software we created. The possible errors, like overcounting or double-stepping, were overcome using design interventions. The optimum breadth of the mat was determined to be 18 inches, after we tested many different versions and observed the average stride length of a person. Otherwise, people might step over the sensor.

We started with a proof of concept built in three days, made out of cardboard and aluminum foil.

(Laughter)

It worked, for real. We built another one with aluminum composite panels and piezoelectric plates, which are plates that generate a small pulse of electricity under pressure. We tested this at 30 different pilots in public, in crowded restaurants, in malls, in temples, etc., to see how people reacted. And people let us run these pilots because they were excited to see localites work on problems for the city. I was 15 and my team members were in their early 20s.

When the sensors were colored, people would get scared and would ask us questions like, "Will I get electrocuted if I step on this?"

(Laughter)

Or, if it was very obvious that it was an electronic sensor on the ground, they would just jump over it.

(Laughter)

So we decided to design a cover for the sensor so that people don't have to worry what it is on the ground.

So after some experimentation, we decided to use an industrial sensor, used as a safety trigger in hazardous areas as the sensor, and a black neoprene rubber sheet as the cover. Now, another added benefit of using black rubber was that dust naturally accumulates over the surface, eventually camouflaging it with the ground. We also had to make sure that the sensor is no higher than 12 millimeters. Otherwise, people might trip over it, which in itself would cause stampedes.

(Laughter)

We don't want that.

(Laughter)

So we were able to design a sensor which was only 10 millimeters thick.

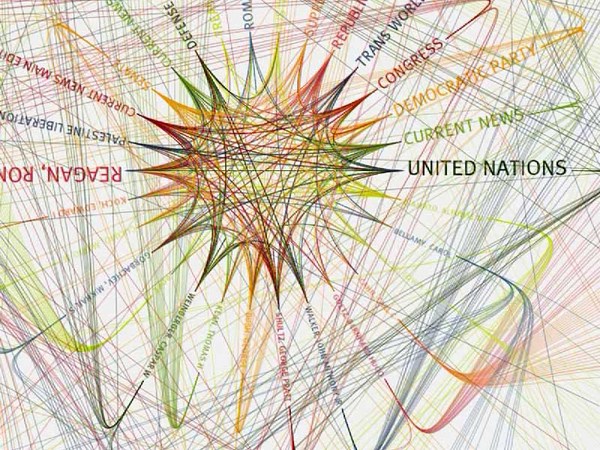

Now the data is sent to the server in real time, and a heat map is plotted, taking into account all the active devices on the ground. The authorities could be alerted if the crowd movement slowed down or if the crowd density moved beyond a desired threshold.

We installed five of these mats in the Nashik Kumbh Mela 2015, and counted over half a million people in 18 hours, ensuring that the data was available in real time at various checkpoints, ensuring a safe flow of people.

Now, this system, eventually, with other innovations, is what helped prevent stampedes altogether at that festival.

The code used by Ashioto during Kumbh Mela will soon be made publicly available, free to use for anyone. I would be glad if someone used this code to make many more gatherings safer.

Having succeeded at Kumbh Mela has inspired me to help others who may also suffer from stampedes. The design of the system makes it adaptable to pretty much any event that involves an organized gathering of people. And my new dream is to improve, adapt and deploy the system all over the world to prevent loss of life and ensure a safe flow of people, because every human soul is precious, whether at concerts or sporting events, the Maha Kumbh Mela in Allahabad, the Hajj in Mecca, the Shia procession to Karbala or at the Vatican City.

So what do you all think, can we do it?

(Audience) Yes!

Thank you.

(Cheers)

(Applause)