One thing I wanted to say about film making is -- about this film -- in thinking about some of the wonderful talks we've heard here, Michael Moschen, and some of the talks about music, this idea that there is a narrative line, and that music exists in time. A film also exists in time; it's an experience that you should go through emotionally. And in making this film I felt that so many of the documentaries I've seen were all about learning something, or knowledge, or driven by talking heads, and driven by ideas. And I wanted this film to be driven by emotions, and really to follow my journey. So instead of doing the talking head thing, instead it's composed of scenes, and we meet people along the way. We only meet them once. They don't come back several times, so it really chronicles a journey. It's something like life, that once you get in it you can't get out.

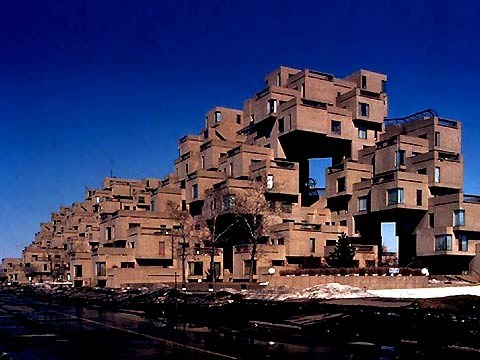

There are two clips I want to show you, the first one is a kind of hodgepodge, its just three little moments, four little moments with three of the people who are here tonight. It's not the way they occur in the film, because they are part of much larger scenes. They play off each other in a wonderful way. And that ends with a little clip of my father, of Lou, talking about something that is very dear to him, which is the accidents of life. I think he felt that the greatest things in life were accidental, and perhaps not planned at all. And those three clips will be followed by a scene of perhaps what, to me, is really his greatest building which is a building in Dhaka, Bangladesh. He built the capital over there. And I think you'll enjoy this building, it's never been seen -- it's been still photographed, but never photographed by a film crew. We were the first film crew in there.

So you'll see images of this remarkable building. A couple of things to keep in mind when you see it, it was built entirely by hand, I think they got a crane the last year. It was built entirely by hand off bamboo scaffolding, people carrying these baskets of concrete on their heads, dumping them in the forms. It is the capital of the country, and it took 23 years to build, which is something they seem to be very proud of over there. It took as long as the Taj Mahal. Unfortunately it took so long that Lou never saw it finished. He died in 1974. The building was finished in 1983. So it continued on for many years after he died. Think about that when you see that building, that sometimes the things we strive for so hard in life we never get to see finished.

And that really struck me about my father, in the sense that he had such belief that somehow, doing these things giving in the way that he gave, that something good would come out of it, even in the middle of a war, there was a war with Pakistan at one point, and the construction stopped totally and he kept working, because he felt, "Well when the war is done they'll need this building." So, those are the two clips I'm going to show. Roll that tape. (Applause)

Richard Saul Wurman: I remember hearing him talk at Penn. And I came home and I said to my father and mother, "I just met this man: doesn't have much work, and he's sort of ugly, funny voice, and he's a teacher at school. I know you've never heard of him, but just mark this day that someday you will hear of him, because he's really an amazing man."

Frank Gehry: I heard he had some kind of a fling with Ingrid Bergman. Is that true?

Nathaniel Kahn: If he did he was a very lucky man.

(Laughter)

NK: Did you hear that, really?

FG: Yeah, when he was in Rome.

Moshe Safdie: He was a real nomad. And you know, when I knew him when I was in the office, he would come in from a trip, and he would be in the office for two or three days intensely, and he would pack up and go. You know he'd be in the office till three in the morning working with us and there was this kind of sense of the nomad in him. I mean as tragic as his death was in a railway station, it was so consistent with his life, you know? I mean I often think I'm going to die in a plane, or I'm going to die in an airport, or die jogging without an identification on me. I don't know why I sort of carry that from that memory of the way he died. But he was a sort of a nomad at heart.

Louis Kahn: How accidental our existences are really and how full of influence by circumstance.

Man: We are the morning workers who come, all the time, here and enjoy the walking, city's beauty and the atmosphere and this is the nicest place of Bangladesh. We are proud of it.

NK: You're proud of it?

Man: Yes, it is the national image of Bangladesh.

NK: Do you know anything about the architect?

Man: Architect? I've heard about him; he's a top-ranking architect.

NK: Well actually I'm here because I'm the architect's son, he was my father.

Man: Oh! Dad is Louis Farrakhan?

NK: Yeah. No not Louis Farrakhan, Louis Kahn.

Man: Louis Kahn, yes!

(Laughter)

Man: Your father, is he alive?

NK: No, he's been dead for 25 years.

Man: Very pleased to welcome you back.

NK: Thank you.

NK: He never saw it finished, Pop. No, he never saw this.

Shamsul Wares: It was almost impossible, building for a country like ours. In 30, 50 years back, it was nothing, only paddy fields, and since we invited him here, he felt that he has got a responsibility. He wanted to be a Moses here, he gave us democracy. He is not a political man, but in this guise he has given us the institution for democracy, from where we can rise. In that way it is so relevant. He didn't care for how much money this country has, or whether he would be able to ever finish this building, but somehow he has been able to do it, build it, here. And this is the largest project he has got in here, the poorest country in the world.

NK: It cost him his life.

SW: Yeah, he paid. He paid his life for this, and that is why he is great and we'll remember him. But he was also human. Now his failure to satisfy the family life, is an inevitable association of great people. But I think his son will understand this, and will have no sense of grudge, or sense of being neglected, I think. He cared in a very different manner, but it takes a lot of time to understand that. In social aspect of his life he was just like a child, he was not at all matured. He could not say no to anything, and that is why, that he cannot say no to things, we got this building today. You see, only that way you can be able to understand him. There is no other shortcut, no other way to really understand him. But I think he has given us this building and we feel all the time for him, that's why, he has given love for us. He could not probably give the right kind of love for you, but for us, he has given the people the right kind of love, that is important. You have to understand that. He had an enormous amount of love, he loved everybody. To love everybody, he sometimes did not see the very closest ones, and that is inevitable for men of his stature.

(Applause)