Space, the final frontier.

I first heard these words when I was just six years old, and I was completely inspired. I wanted to explore strange new worlds. I wanted to seek out new life. I wanted to see everything that the universe had to offer. And those dreams, those words, they took me on a journey, a journey of discovery, through school, through university, to do a PhD and finally to become a professional astronomer. Now, I learned two amazing things, one slightly unfortunate, when I was doing my PhD. I learned that the reality was I wouldn't be piloting a starship anytime soon. But I also learned that the universe is strange, wonderful and vast, actually too vast to be explored by spaceship. And so I turned my attention to astronomy, to using telescopes.

Now, I show you before you an image of the night sky. You might see it anywhere in the world. And all of these stars are part of our local galaxy, the Milky Way. Now, if you were to go to a darker part of the sky, a nice dark site, perhaps in the desert, you might see the center of our Milky Way galaxy spread out before you, hundreds of billions of stars. And it's a very beautiful image. It's colorful. And again, this is just a local corner of our universe. You can see there's a sort of strange dark dust across it. Now, that is local dust that's obscuring the light of the stars. But we can do a pretty good job. Just with our own eyes, we can explore our little corner of the universe. It's possible to do better. You can use wonderful telescopes like the Hubble Space Telescope. Now, astronomers have put together this image. It's called the Hubble Deep Field, and they've spent hundreds of hours observing just a tiny patch of the sky no larger than your thumbnail held at arm's length. And in this image you can see thousands of galaxies, and we know that there must be hundreds of millions, billions of galaxies in the entire universe, some like our own and some very different. So you think, OK, well, I can continue this journey. This is easy. I can just use a very powerful telescope and just look at the sky, no problem. It's actually really missing out if we just do that. Now, that's because everything I've talked about so far is just using the visible spectrum, just the thing that your eyes can see, and that's a tiny slice, a tiny, tiny slice of what the universe has to offer us. Now, there's also two very important problems with using visible light. Not only are we missing out on all the other processes that are emitting other kinds of light, but there's two issues.

Now, the first is that dust that I mentioned earlier. The dust stops the visible light from getting to us. So as we look deeper into the universe, we see less light. The dust stops it getting to us. But there's a really strange problem with using visible light in order to try and explore the universe.

Now take a break for a minute. Say you're standing on a corner, a busy street corner. There's cars going by. An ambulance approaches. It has a high-pitched siren.

(Imitates a siren passing by)

The siren appeared to change in pitch as it moved towards and away from you. The ambulance driver did not change the siren just to mess with you. That was a product of your perception. The sound waves, as the ambulance approached, were compressed, and they changed higher in pitch. As the ambulance receded, the sound waves were stretched, and they sounded lower in pitch. The same thing happens with light. Objects moving towards us, their light waves are compressed and they appear bluer. Objects moving away from us, their light waves are stretched, and they appear redder. So we call these effects blueshift and redshift.

Now, our universe is expanding, so everything is moving away from everything else, and that means everything appears to be red. And oddly enough, as you look more deeply into the universe, more distant objects are moving away further and faster, so they appear more red. So if I come back to the Hubble Deep Field and we were to continue to peer deeply into the universe just using the Hubble, as we get to a certain distance away, everything becomes red, and that presents something of a problem. Eventually, we get so far away everything is shifted into the infrared and we can't see anything at all.

So there must be a way around this. Otherwise, I'm limited in my journey. I wanted to explore the whole universe, not just whatever I can see, you know, before the redshift kicks in. There is a technique. It's called radio astronomy. Astronomers have been using this for decades. It's a fantastic technique. I show you the Parkes Radio Telescope, affectionately known as "The Dish." You may have seen the movie. And radio is really brilliant. It allows us to peer much more deeply. It doesn't get stopped by dust, so you can see everything in the universe, and redshift is less of a problem because we can build receivers that receive across a large band.

So what does Parkes see when we turn it to the center of the Milky Way? We should see something fantastic, right? Well, we do see something interesting. All that dust has gone. As I mentioned, radio goes straight through dust, so not a problem. But the view is very different. We can see that the center of the Milky Way is aglow, and this isn't starlight. This is a light called synchrotron radiation, and it's formed from electrons spiraling around cosmic magnetic fields. So the plane is aglow with this light. And we can also see strange tufts coming off of it, and objects which don't appear to line up with anything that we can see with our own eyes. But it's hard to really interpret this image, because as you can see, it's very low resolution. Radio waves have a wavelength that's long, and that makes their resolution poorer. This image is also black and white, so we don't really know what is the color of everything in here.

Well, fast-forward to today. We can build telescopes which can get over these problems. Now, I'm showing you here an image of the Murchison Radio Observatory, a fantastic place to build radio telescopes. It's flat, it's dry, and most importantly, it's radio quiet: no mobile phones, no Wi-Fi, nothing, just very, very radio quiet, so a perfect place to build a radio telescope. Now, the telescope that I've been working on for a few years is called the Murchison Widefield Array, and I'm going to show you a little time lapse of it being built. This is a group of undergraduate and postgraduate students located in Perth. We call them the Student Army, and they volunteered their time to build a radio telescope. There's no course credit for this. And they're putting together these radio dipoles. They just receive at low frequencies, a bit like your FM radio or your TV. And here we are deploying them across the desert. The final telescope covers 10 square kilometers of the Western Australian desert. And the interesting thing is, there's no moving parts. We just deploy these little antennas essentially on chicken mesh. It's fairly cheap. Cables take the signals from the antennas and bring them to central processing units. And it's the size of this telescope, the fact that we've built it over the entire desert that gives us a better resolution than Parkes.

Now, eventually all those cables bring them to a unit which sends it off to a supercomputer here in Perth, and that's where I come in.

(Sighs)

Radio data. I have spent the last five years working with very difficult, very interesting data that no one had really looked at before. I've spent a long time calibrating it, running millions of CPU hours on supercomputers and really trying to understand that data. And with this telescope, with this data, we've performed a survey of the entire southern sky, the GaLactic and Extragalactic All-sky MWA Survey, or GLEAM, as I call it. And I'm very excited. This survey is just about to be published, but it hasn't been shown yet, so you are literally the first people to see this southern survey of the entire sky. So I'm delighted to share with you some images from this survey.

Now, imagine you went to the Murchison, you camped out underneath the stars and you looked towards the south. You saw the south's celestial pole, the galaxy rising. If I fade in the radio light, this is what we observe with our survey. You can see that the galactic plane is no longer dark with dust. It's alight with synchrotron radiation, and thousands of dots are in the sky. Our large Magellanic Cloud, our nearest galactic neighbor, is orange instead of its more familiar blue-white.

So there's a lot going on in this. Let's take a closer look. If we look back towards the galactic center, where we originally saw the Parkes image that I showed you earlier, low resolution, black and white, and we fade to the GLEAM view, you can see the resolution has gone up by a factor of a hundred. We now have a color view of the sky, a technicolor view. Now, it's not a false color view. These are real radio colors. What I've done is I've colored the lowest frequencies red and the highest frequencies blue, and the middle ones green. And that gives us this rainbow view. And this isn't just false color. The colors in this image tell us about the physical processes going on in the universe. So for instance, if you look along the plane of the galaxy, it's alight with synchrotron, which is mostly reddish orange, but if we look very closely, we see little blue dots. Now, if we zoom in, these blue dots are ionized plasma around very bright stars, and what happens is that they block the red light, so they appear blue. And these can tell us about these star-forming regions in our galaxy. And we just see them immediately. We look at the galaxy, and the color tells us that they're there.

You can see little soap bubbles, little circular images around the galactic plane, and these are supernova remnants. When a star explodes, its outer shell is cast off and it travels outward into space gathering up material, and it produces a little shell. It's been a long-standing mystery to astronomers where all the supernova remnants are. We know that there must be a lot of high-energy electrons in the plane to produce the synchrotron radiation that we see, and we think they're produced by supernova remnants, but there don't seem to be enough. Fortunately, GLEAM is really, really good at detecting supernova remnants, so we're hoping to have a new paper out on that soon.

Now, that's fine. We've explored our little local universe, but I wanted to go deeper, I wanted to go further. I wanted to go beyond the Milky Way. Well, as it happens, we can see a very interesting object in the top right, and this is a local radio galaxy, Centaurus A. If we zoom in on this, we can see that there are two huge plumes going out into space. And if you look right in the center between those two plumes, you'll see a galaxy just like our own. It's a spiral. It has a dust lane. It's a normal galaxy. But these jets are only visible in the radio. If we looked in the visible, we wouldn't even know they were there, and they're thousands of times larger than the host galaxy.

What's going on? What's producing these jets? At the center of every galaxy that we know about is a supermassive black hole. Now, black holes are invisible. That's why they're called that. All you can see is the deflection of the light around them, and occasionally, when a star or a cloud of gas comes into their orbit, it is ripped apart by tidal forces, forming what we call an accretion disk. The accretion disk glows brightly in the x-rays, and huge magnetic fields can launch the material into space at nearly the speed of light. So these jets are visible in the radio and this is what we pick up in our survey.

Well, very well, so we've seen one radio galaxy. That's nice. But if you just look at the top of that image, you'll see another radio galaxy. It's a little bit smaller, and that's just because it's further away. OK. Two radio galaxies. We can see this. This is fine. Well, what about all the other dots? Presumably those are just stars. They're not. They're all radio galaxies. Every single one of the dots in this image is a distant galaxy, millions to billions of light-years away with a supermassive black hole at its center pushing material into space at nearly the speed of light. It is mind-blowing. And this survey is even larger than what I've shown here. If we zoom out to the full extent of the survey, you can see I found 300,000 of these radio galaxies. So it's truly an epic journey. We've discovered all of these galaxies right back to the very first supermassive black holes. I'm very proud of this, and it will be published next week.

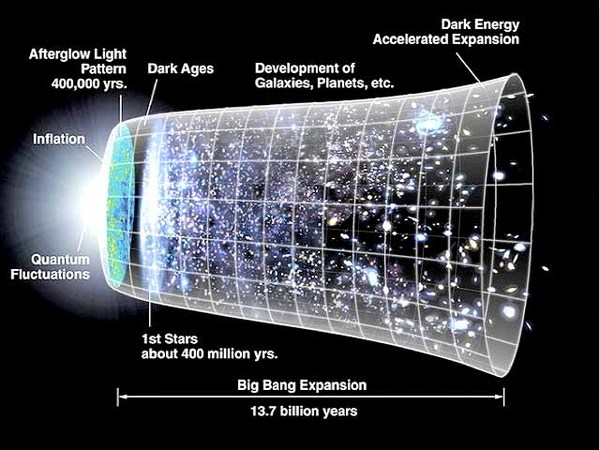

Now, that's not all. I've explored the furthest reaches of the galaxy with this survey, but there's something even more in this image. Now, I'll take you right back to the dawn of time. When the universe formed, it was a big bang, which left the universe as a sea of hydrogen, neutral hydrogen. And when the very first stars and galaxies switched on, they ionized that hydrogen. So the universe went from neutral to ionized. That imprinted a signal all around us. Everywhere, it pervades us, like the Force. Now, because that happened so long ago, the signal was redshifted, so now that signal is at very low frequencies. It's at the same frequency as my survey, but it's so faint. It's a billionth the size of any of the objects in my survey. So our telescope may not be quite sensitive enough to pick up this signal. However, there's a new radio telescope. So I can't have a starship, but I can hopefully have one of the biggest radio telescopes in the world. We're building the Square Kilometre Array, a new radio telescope, and it's going to be a thousand times bigger than the MWA, a thousand times more sensitive, and have an even better resolution. So we should find tens of millions of galaxies. And perhaps, deep in that signal, I will get to look upon the very first stars and galaxies switching on, the beginning of time itself.

Thank you.

(Applause)