The history of civilization, in some ways, is a history of maps: How have we come to understand the world around us? One of the most famous maps works because it really isn't a map at all.

[Small thing. Big idea.]

[Michael Bierut on the London Tube Map]

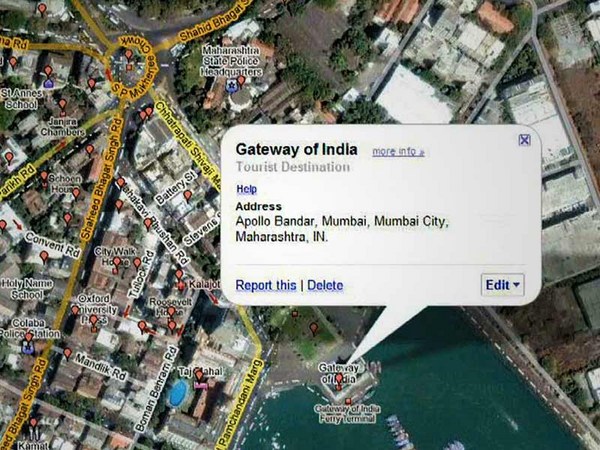

The London Underground came together in 1908, when eight different independent railways merged to create a single system. They needed a map to represent that system so people would know where to ride. The map they made is complicated. You can see rivers, bodies of water, trees and parks -- the stations were all crammed together at the center of the map, and out in the periphery, there were some that couldn't even fit on the map. So the map was geographically accurate, but maybe not so useful.

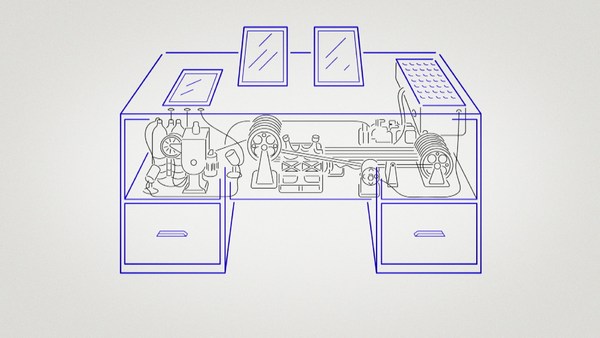

Enter Harry Beck. Harry Beck was a 29-year-old engineering draftsman who had been working on and off for the London Underground. And he had a key insight, and that was that people riding underground in trains don't really care what's happening aboveground. They just want to get from station to station -- "Where do I get on? Where do I get off?" It's the system that's important, not the geography. He's taken this complicated mess of spaghetti, and he's simplified it. The lines only go in three directions: they're horizontal, they're vertical, or they're 45 degrees. Likewise, he spaced the stations equally, he's made every station color correspond to the color of the line, and he's fixed it all so that it's not really a map anymore. What it is is a diagram, just like circuitry, except the circuitry here isn't wires conducting electrons, it's tubes containing trains conducting people from place to place.

In 1933, the Underground decided, at last, to give Harry Beck's map a try. The Underground did a test run of a thousand of these maps, pocket-size. They were gone in one hour. They realized they were onto something, they printed 750,000 more, and this is the map that you see today.

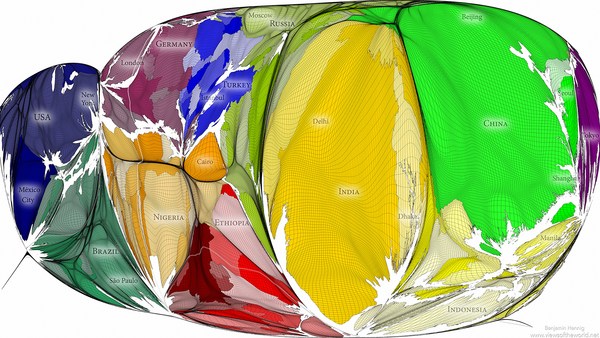

Beck's design really became the template for the way we think of metro maps today. Tokyo, Paris, Berlin, São Paulo, Sydney, Washington, D.C. -- all of them convert complex geography into crisp geometry. All of them use different colors to distinguish between lines, all of them use simple symbols to distinguish between types of stations. They all are part of a universal language, seemingly.

I bet Harry Beck wouldn't have known what a user interface was, but that's really what he designed and he really took that challenge and broke it down to three principles that I think can be applied in nearly any design problem. First one is focus. Focus on who you're doing this for. The second principle is simplicity. What's the shortest way to deliver that need? Finally, the last thing is: Thinking in a cross-disciplinary way. Who would've thought that an electrical engineer would be the person to hold the key to unlock what was then one of the most complicated systems in the world -- all started by one guy with a pencil and an idea.