Let's imagine together we've gone on an eight-month journey and arrived to the planet Mars. Yes, Mars. Somehow we'll have to figure out how to build protective and durable structures to shield us against solar radiation, galactic cosmic rays and extreme temperatures swings. On a Mars mission, there's only so much that we can bring with us from Earth. And it's prohibitively expensive to launch tons and tons of construction materials into space.

So to realize a pioneering habitat that progressively grows, adapts and expands into a permanent outpost, we have to think differently about how we build. These habitats and the robots that build them will enable humanity to thrive off-world.

I am a space architect. I design and conceive habitats supporting human exploration in deep space, like on the surface of Mars. Not only do I design spaces for optimal crew health and performance, but I also investigate what these habitats are and how they're going to be built.

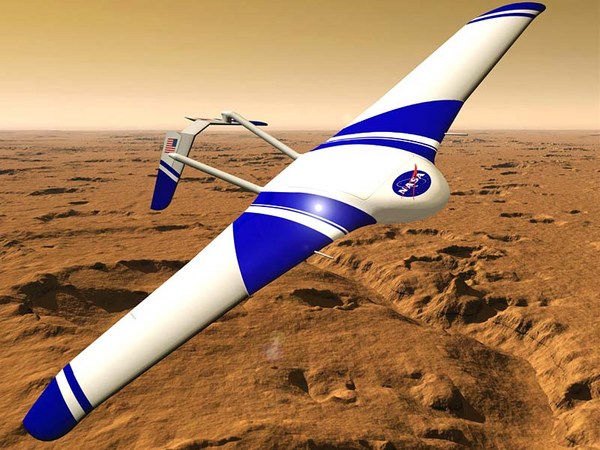

Now, Mars is so far from us that communications delays can take up to 22 minutes one way to or from Earth. And what that means is that we can't rely on real-time telerobotics controlled by people on Earth to supervise what happens in construction on Mars or for that matter, to supervise anything that happens when we're exploring the planet. But if we leverage autonomous robotics, we'll send 3D printers and other construction robots to build protective habitats and shelters before the crew even arrives.

So how exactly would 3D printers build a habitat on Mars? Well, first we have to figure out what these structures are made out of. Just like early civilizations, will use in situ regolith, commonly known as dirt, and other resources that are local and indigenous to the planet, including water, and possibly combine them with additives and binders that we bring from Earth to engineer high-performance construction materials. Our goal when we're designing these habitats is to introduce an airtight structure that can withstand internal pressurization, which is what will allow people to live in a breathable and temperate environment on the inside.

The robots that we deploy on Mars will need to perceive and interpret the complexity of a construction site in order to sequence and choreograph different types of tasks. These tasks will include prospecting Mars and surveying for a site to build, collecting raw materials, processing those materials and maneuvering them around. Some of these bots might resemble the character Wall-E, except, you know, not so cute. Once the site has been excavated and foundations are printed, these structures are manufactured layer by layer by layer. And as construction progresses, prebuilt and preintegrated hardware like airlocks or life support equipment brought from Earth are inserted into the print until finally they're sealed at various connection points.

To do more than just survive in space, we need to create environments that positively contribute to well-being for months and years into the future. And as more civilian astronauts travel to space, it's important that our environments are more than the tightly packed mechanical interiors of the International Space Station, which today represents the state of the art for long-duration human life in space. We also want to incorporate practical architectural elements such as access to natural light through windows and greenery. These were features that were missing aboard the space station when it was first commissioned, but which we know are critical to positive psychological functioning and well-being. For long duration missions in deep space, it's important that crew members feel less like they're living in a machine and more like they're living in a home.

There are other ways of approaching habitat construction on Mars. Hard-shell or inflatable structures may not provide the radiation protection that we need, and living underground in lava tubes doesn't quite support direct surface exploration on the planet. And also, why would you travel for eight months to live underground? Designing structures in space is all about mitigating risks and the habitats that we create will need to be the most durable and the most resilient structures ever conceived. Future off-world surface habitats will be self-regulating and self-maintained structures to support the crew members while they're there, but also to operate autonomously when they are not.

Before we send anyone to Mars, we need data to answer some very key questions about human health, safety, and to validate each of these construction activities. Fortunately for us, we have a testbed and a proving ground much, much closer to Earth. That's our own Moon. Today we're working with NASA to demonstrate how we'll 3D-print infrastructure like landing pads, roadways and eventually habitats directly on the lunar surface. The Moon is a critical pit stop to refuel, resupply and serve as a general platform for vehicles traveling to deep space, and we'll use the technologies establishing a permanent human presence on the Moon to travel to, from and operate on the surface of Mars.

What else are we doing to advance the viability of 3D printing for building in space? Well, for one thing, we can demonstrate that 3D-printed structures can support people in a mission-like environment right here on Earth, and use data from those experiments to set standards and requirements for future Mars missions. This is what we did in designing and building Mars Dune Alpha, a 3D-printed analog habitat at the Johnson Space Center in Houston, referred to as the Crew Health and Performance Exploration Analog -- that's a really long name, I know -- this structure will house four volunteer crew members simulating a one-year mission to Mars, including a 20-minute communications delay. The first mission is kicking off later this year, but you could actually apply to be a crew member in this habitat sometime in the future. Or if you're not so inclined, you can suggest it to someone else in the name of research.

(Laughter) If you're one of the chosen few, you'll be sharing 1700 square feet of living and working areas with three others, and that includes an aeroponic garden for plant growth, a communications area, an exercise room, as well as individual crew cabins that are very cozy, just six by 12 feet.

Some of you may be thinking, "Well, building in space, this is a topic pretty far removed from our day-to-day lives. How might it impact what we do on Earth today? In my experience, designing for an extreme environment that is the most restrictive and that presents the most constraints, and which literally no human has ever gone before, is what gives us the best chances of creatively engineering solutions to problems here on Earth that seem completely beyond our grasp today. Problems like housing solutions for the chronically homeless or hurricane and disaster relief housing. Or rethinking sustainable practices within construction overall, which, according to the UN, is responsible for up to 30 percent of carbon emissions worldwide. The autonomous technologies that we develop for building in space redound to us on Earth. They feed back and pay dividends to how we reimagine and reconceive construction happening today.

The fact of the matter is that the most habitable planet is the one we live on right now. I don't like treating space like it's a lifeboat for humanity from an ailing planet Earth. We can either solve for how to build smarter and more sustainably today, or we'll have to think about designing for survival on an Earth more extreme and more foreign than any of us have ever known. And this to me cannot be the primary reason or driver why we explore and venture into deep space.

It's been over 50 years since any human has traveled outside of Earth's orbit. Things are about to change. We will develop a permanent Moon base, and we will build autonomously on Mars. We are on the cusp of seeing radical transformation and how we build on Earth and how we push past limits to a new frontier of human exploration in space.

Thank you so much.

(Applause)