So, well, I do applied math, and this is a peculiar problem for anyone who does applied math, is that we are like management consultants. No one knows what the hell we do. So I am going to give you some -- attempt today to try and explain to you what I do.

So, dancing is one of the most human of activities. We delight at ballet virtuosos and tap dancers you will see later on. Now, ballet requires an extraordinary level of expertise and a high level of skill, and probably a level of initial suitability that may well have a genetic component to it. Now, sadly, neurological disorders such as Parkinson's disease gradually destroy this extraordinary ability, as it is doing to my friend Jan Stripling, who was a virtuoso ballet dancer in his time. So great progress and treatment has been made over the years. However, there are 6.3 million people worldwide who have the disease, and they have to live with incurable weakness, tremor, rigidity and the other symptoms that go along with the disease, so what we need are objective tools to detect the disease before it's too late. We need to be able to measure progression objectively, and ultimately, the only way we're going to know when we actually have a cure is when we have an objective measure that can answer that for sure.

But frustratingly, with Parkinson's disease and other movement disorders, there are no biomarkers, so there's no simple blood test that you can do, and the best that we have is like this 20-minute neurologist test. You have to go to the clinic to do it. It's very, very costly, and that means that, outside the clinical trials, it's just never done. It's never done.

But what if patients could do this test at home? Now, that would actually save on a difficult trip to the clinic, and what if patients could do that test themselves, right? No expensive staff time required. Takes about $300, by the way, in the neurologist's clinic to do it.

So what I want to propose to you as an unconventional way in which we can try to achieve this, because, you see, in one sense, at least, we are all virtuosos like my friend Jan Stripling.

So here we have a video of the vibrating vocal folds. Now, this is healthy and this is somebody making speech sounds, and we can think of ourselves as vocal ballet dancers, because we have to coordinate all of these vocal organs when we make sounds, and we all actually have the genes for it. FoxP2, for example. And like ballet, it takes an extraordinary level of training. I mean, just think how long it takes a child to learn to speak. From the sound, we can actually track the vocal fold position as it vibrates, and just as the limbs are affected in Parkinson's, so too are the vocal organs. So on the bottom trace, you can see an example of irregular vocal fold tremor. We see all the same symptoms. We see vocal tremor, weakness and rigidity. The speech actually becomes quieter and more breathy after a while, and that's one of the example symptoms of it.

So these vocal effects can actually be quite subtle, in some cases, but with any digital microphone, and using precision voice analysis software in combination with the latest in machine learning, which is very advanced by now, we can now quantify exactly where somebody lies on a continuum between health and disease using voice signals alone.

So these voice-based tests, how do they stack up against expert clinical tests? We'll, they're both non-invasive. The neurologist's test is non-invasive. They both use existing infrastructure. You don't have to design a whole new set of hospitals to do it. And they're both accurate. Okay, but in addition, voice-based tests are non-expert. That means they can be self-administered. They're high-speed, take about 30 seconds at most. They're ultra-low cost, and we all know what happens. When something becomes ultra-low cost, it becomes massively scalable. So here are some amazing goals that I think we can deal with now. We can reduce logistical difficulties with patients. No need to go to the clinic for a routine checkup. We can do high-frequency monitoring to get objective data. We can perform low-cost mass recruitment for clinical trials, and we can make population-scale screening feasible for the first time. We have the opportunity to start to search for the early biomarkers of the disease before it's too late.

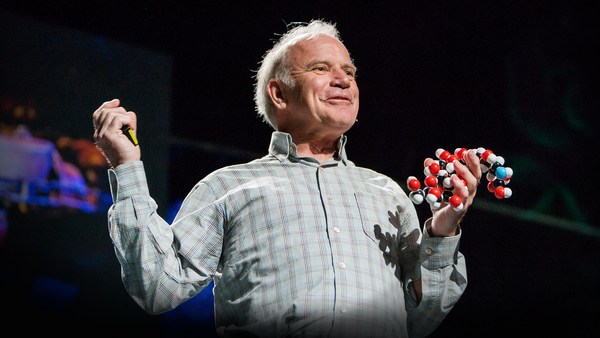

So, taking the first steps towards this today, we're launching the Parkinson's Voice Initiative. With Aculab and PatientsLikeMe, we're aiming to record a very large number of voices worldwide to collect enough data to start to tackle these four goals. We have local numbers accessible to three quarters of a billion people on the planet. Anyone healthy or with Parkinson's can call in, cheaply, and leave recordings, a few cents each, and I'm really happy to announce that we've already hit six percent of our target just in eight hours. Thank you. (Applause) (Applause)

Tom Rielly: So Max, by taking all these samples of,

let's say, 10,000 people, you'll be able to tell who's healthy and who's not? What are you going to get out of those samples?

Max Little: Yeah. Yeah. So what will happen is that, during the call you have to indicate whether or not you have the disease or not, you see. TR: Right. ML: You see, some people may not do it. They may not get through it. But we'll get a very large sample of data that is collected from all different circumstances, and it's getting it in different circumstances that matter because then we are looking at ironing out the confounding factors, and looking for the actual markers of the disease.

TR: So you're 86 percent accurate right now?

ML: It's much better than that. Actually, my student Thanasis, I have to plug him, because he's done some fantastic work, and now he has proved that it works over the mobile telephone network as well, which enables this project, and we're getting 99 percent accuracy.

TR: Ninety-nine. Well, that's an improvement. So what that means is that people will be able to — ML: (Laughs) TR: People will be able to call in from their mobile phones and do this test, and people with Parkinson's could call in, record their voice, and then their doctor can check up on their progress, see where they're doing in this course of the disease.

ML: Absolutely.

TR: Thanks so much. Max Little, everybody.

ML: Thanks, Tom. (Applause)