We're now becoming aware of a significant relationship between sleep and Alzheimer's disease.

[Sleeping with Science]

Now, Alzheimer's disease is a form of dementia typified usually by memory loss and memory decline. And what we've started to understand is that there are several different proteins that seem to go awry in Alzheimer's disease. One of those proteins is a sticky, toxic substance called beta-amyloid that builds up in the brain. The other is something called tau protein. How are these things related to sleep?

Well first, if we look at a large-scale epidemiological level, what we know is that individuals who report sleeping typically less than six hours a night, have a significantly higher risk of going on to develop high amounts of that beta-amyloid in their brain later in life. We also know that two sleep disorders, including insomnia and sleep apnea, or heavy snoring, are associated with a significantly higher risk of Alzheimer's disease in late life.

Those are, of course, simply associational studies. They don't prove causality. But more recently, we actually have identified that causal evidence. In fact, if you take a healthy human being and you deprive them of sleep for just one night, and the next day, we see an immediate increase in that beta-amyloid, both circulating in their bloodstream, circulating in what we call the cerebrospinal fluid, and most recently, after just one night of sleep, using special brain-imaging technology, scientists have found that there is an immediate increase in beta-amyloid directly in the brain itself.

So that's the causal evidence. What is it then about sleep that seems to provide a mechanism that prevents the escalation of these Alzheimer's-related proteins? Well, several years ago, a scientist called Maiken Nedergaard made a remarkable discovery. What she identified was a cleansing system in the brain. Now, before that, we knew that the body had a cleansing system and many of you may be familiar with this. It's called the lymphatic system. But we didn't think that the brain had its own cleansing system. And studying mice, she was actually able to identify a sewage system within the brain called the glymphatic system, named after the cells that make it up, called these glial cells.

Now, if that wasn't remarkable enough, she went on to make two more incredible discoveries. First, what she found is that that cleansing system in the brain is not always switched on in high-flow volume across the 24-hour period. Instead, it was when those mice were actually sleeping, particularly when they went into deep non-REM sleep, that that cleansing system kicked into high gear.

The third component that she discovered, and this is what makes it relevant to our discussion on Alzheimer's disease, is that one of the metabolic by-products, one of the toxins that was cleared away during sleep, was that sticky, toxic protein, beta-amyloid, linked to Alzheimer's disease. And just recently, scientists in Boston have discovered a very similar type of pulsing, cleansing brain-mechanism in human beings as well.

Now, some of this discussion may sound perhaps a little depressing. We know that as we get older in life, our sleep seems to typically decline, and our risk for Alzheimer's generally increases. But I think there's actually a silver lining here, because unlike many of the other factors that are associated with aging and Alzheimer's disease, for example, changes in the physical structure of the brain, those are fiendishly difficult to treat and medicine doesn't have any good wholesale approaches right now. But that sleep is a missing piece in the explanatory puzzle of aging and Alzheimer's disease is exciting because we may be able to do something about it.

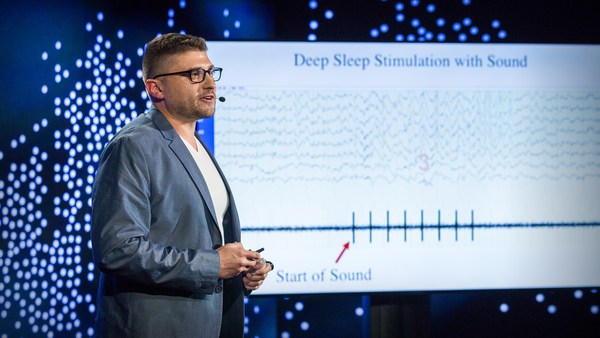

What if we could actually augment human sleep and try to improve the quality of that deep sleep in midlife, which is when we start to see the decline in deep sleep beginning to happen. What if we could actually shift from a model of late-stage treatment in Alzheimer's disease to a model of midlife prevention? Could we go from sick care to actually healthcare? And by modifying sleep, could we actually bend the arrow of Alzheimer's disease risk down on itself?

That's something that I'm incredibly excited about and something that we're actively researching right now.