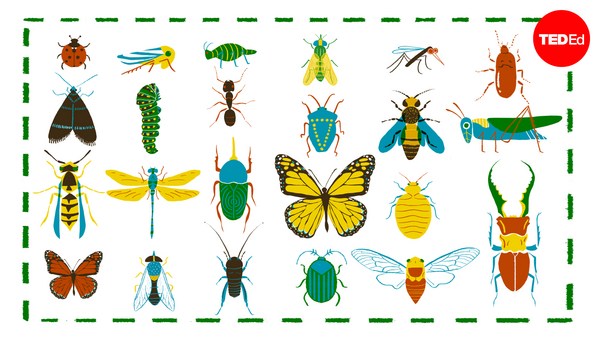

So, people are more afraid of insects than they are of dying. (Laughter) At least, according to a 1973 "Book of Lists" survey which preceded all those online best, worst, funniest lists that you see today. Only heights and public speaking exceeded the six-legged as sources of fear. And I suspect if you had put spiders in there, the combinations of insects and spiders would have just topped the chart. Now, I am not one of those people. I really love insects. I think they're interesting and beautiful, and sometimes even cute. (Laughter) And I'm not alone. For centuries, some of the greatest minds in science, from Charles Darwin to E.O. Wilson, have drawn inspiration from studying some of the smallest minds on Earth. Well, why is that? What is that keeps us coming back to insects? Some of it, of course, is just the sheer magnitude of almost everything about them. They're more numerous than any other kind of animal. We don't even know how many species of insects there are, because new ones are being discovered all the time. There are at least a million, maybe as many as 10 million. This means that you could have an insect-of-the-month calendar and not have to reuse a species for over 80,000 years. (Laughter) Take that, pandas and kittens! (Laughter)

More seriously, insects are essential. We need them. It's been estimated that 1 out of every 3 bites of food is made possible by a pollinator. Scientist use insects to make fundamental discoveries about everything from the structure of our nervous systems to how our genes and DNA work. But what I love most about insects is what they can tell us about our own behavior. Insects seem like they do everything that people do. They meet, they mate, they fight, they break up. And they do so with what looks like love or animosity. But what drives their behaviors is really different than what drives our own, and that difference can be really illuminating. There's nowhere where that's more true than when it comes to one of our most consuming interests -- sex.

Now, I will maintain. and I think I can defend, what may seem like a surprising statement. I think sex in insects is more interesting than sex in people. (Laughter) And the wild variety that we see makes us challenge some of our own assumptions about what it means to be male and female. Of course, to start with, a lot of insects don't need to have sex at all to reproduce. Female aphids can make little, tiny clones of themselves without ever mating. Virgin birth, right there. On your rose bushes. (Laughter) When they do have sex, even their sperm is more interesting than human sperm. There are some kinds of fruit flies whose sperm is longer than the male's own body. And that's important because the males use their sperm to compete. Now, male insects do compete with weapons, like the horns on these beetles. But they also compete after mating with their sperm. Dragonflies and damselflies have penises that look kind of like Swiss Army knives with all of the attachments pulled out. (Laughter) They use these formidable devices like scoops, to remove the sperm from previous males that the female has mated with. (Laughter) So, what can we learn from this? (Laughter) All right, it is not a lesson in the sense of us imitating them or of them setting an example for us to follow. Which, given this, is probably just as well. And also, did I mention sexual cannibalism is rampant among insects? So, no, that's not the point. But what I think insects do, is break a lot of the rules that we humans have about the sex roles. So, people have this idea that nature dictates kind of a 1950s sitcom version of what males and females are like. So that males are always supposed to be dominant and aggressive, and females are passive and coy.

But that's just not the case. So for example, take katydids, which are relatives of crickets and grasshoppers. The males are very picky about who they mate with, because they not only transfer sperm during mating, they also give the female something called a nuptial gift. You can see two katydids mating in these photos. In both panels, the male's the one on the right, and that sword-like appendage is the female's egg-laying organ. The white blob is the sperm, the green blob is the nuptial gift, and the male manufactures this from his own body and it's extremely costly to produce. It can weigh up to a third of his body mass. I will now pause for a moment and let you think about what it would be like if human men, every time they had sex, had to produce something that weighed 50, 60, 70 pounds. (Laughter) Okay, they would not be able to do that very often. (Laughter) And indeed, neither can the katydids. And so what that means is the katydid males are very choosy about who they offer these nuptial gifts to. Now, the gift is very nutritious, and the female eats it during and after mating. So, the bigger it is, the better off the male is, because that means more time for his sperm to drain into her body and fertilize her eggs. But it also means that the males are very passive about mating, whereas the females are extremely aggressive and competitive, in an attempt to get as many of these nutritious nuptial gifts as they can. So, it's not exactly a stereotypical set of rules. Even more generally though, males are actually not all that important in the lives of a lot of insects. In the social insects -- the bees and wasps and ants -- the individuals that you see every day -- the ants going back and forth to your sugar bowl, the honey bees that are flitting from flower to flower -- all of those are always female. People have had a hard time getting their head around that idea for millennia. The ancient Greeks knew that there was a class of bees, the drones, that are larger than the workers, although they disapproved of the drones' laziness because they could see that the drones just hang around the hive until the mating flight -- they're the males. They hang around until the mating flight, but they don't participate in gathering nectar or pollen. The Greeks couldn't figure out the drones' sex, and part of the confusion was that they were aware of the stinging ability of bees but they found it difficult to believe that any animals that bore such a weapon could possibly be a female. Aristotle tried to get involved as well. He suggested, "OK, if the stinging individuals are going to be the males ..." Then he got confused, because that would have meant the males were also taking care of the young in a colony, and he seemed to think that would be completely impossible. He then concluded that maybe bees had the organs of both sexes in the same individual, which is not that far-fetched, some animals do that, but he never really did get it figured out. And you know, even today, my students, for instance, call every animal they see, including insects, a male. And when I tell them that the ferocious army-ant soldiers with their giant jaws, used to defend the colony, are all always female, they seem to not quite believe me. (Laughter) And certainly all of the movies -- Antz, Bee Movie -- portray the main character in the social insects as being male. Well, what difference does this make? These are movies. They're fiction. They have talking animals in them. What difference does it make if they talk like Jerry Seinfeld? I think it does matter, and it's a problem that actually is part of a much deeper one that has implications for medicine and health and a lot of other aspects of our lives. You all know that scientists use what we call model systems, which are creatures -- white rats or fruit flies -- that are kind of stand-ins for all other animals, including people. And the idea is that what's true for a person will also be true for the white rat. And by and large, that turns out to be the case. But you can take the idea of a model system too far. And what I think we've done, is use males, in any species, as though they are the model system. The norm. The way things are supposed to be. And females as a kind of variant -- something special that you only study after you get the basics down. And so, back to the insects. I think what that means is that people just couldn't see what was in front of them. Because they assumed that the world's stage was largely occupied by male players and females would only have minor, walk-on roles. But when we do that, we really miss out on a lot of what nature is like. And we can also miss out on the way natural, living things, including people, can vary. And I think that's why we've used males as models in a lot of medical research, something that we know now to be a problem if we want the results to apply to both men and women. Well, the last thing I really love about insects is something that a lot of people find unnerving about them. They have little, tiny brains with very little cognitive ability, the way we normally think of it. They have complicated behavior, but they lack complicated brains. And so, we can't just think of them as though they're little people because they don't do things the way that we do. I really love that it's difficult to anthropomorphize insects, to look at them and just think of them like they're little people in exoskeletons, with six legs. (Laughter) Instead, you really have to accept them on their own terms, because insects make us question what's normal and what's natural. Now, you know, people write fiction and talk about parallel universes. They speculate about the supernatural, maybe the spirits of the departed walking among us. The allure of another world is something that people say is part of why they want to dabble in the paranormal. But as far as I'm concerned, who needs to be able to see dead people, when you can see live insects? Thank you. (Applause)