[The Universe in Verse]

[Prelude]

In 1908, Henrietta Swan Leavitt, one of the women known as the Harvard Computers, who changed our understanding of the universe long before they could vote, was cataloging photographic plates at the Harvard College Observatory, single-handedly analyzing 2,000 variable stars -- stars with fluctuating brightness, kind of like a lighthouse beacon -- when she began noticing a distinct correlation between their brightness and their blinking pattern. That correlation made it possible to measure the distance of stars for the very first time, furnishing the yardstick of the universe.

Meanwhile, a dutiful teenage boy in the Midwest was repressing his childhood love of astronomy and beginning his legal studies to fulfill his dying father's demand for an ordinary, reputable life. When his father died, Edwin Hubble turned that passion for the stars into formal study and discovered two revolutionary facts about the universe: that it is tremendously bigger than we thought and that it's getting bigger and bigger by the blink.

One October evening in 1923, perched at the foot of the largest telescope in the world, at Mount Wilson Observatory, not far from here, Hubble took a 45-minute exposure of Andromeda, which was then thought to be one of many spiral nebulae in our Milky Way. The notion of a galaxy, a gravitationally bound cluster of stars and dust and dark matter, didn't exist at the time. The Milky Way, which, by the way, was coined as a term by Chaucer in the 14th century, was thought to be what was called an "island universe" beyond the edge of which lay cold, dark nothingness. But when Hubble looked at the photograph the next morning and compared it to previous ones, he furrowed his brow and with a gasp of revelation scribbled right on top of the plate "VAR" and then drew an exclamation point because he had realized that a tiny fleck in Andromeda previously thought to be a nova could not possibly be a nova, given its blinking pattern across these different photographs. And it was, in fact, a variable star. Which meant, given Henrietta Leavitt's data, that it was very, very far away, farther than the edge of the Milky Way. Which meant that Andromeda was not a nebula in our own galaxy, but a whole other galaxy, out there, in the cold, dark nothingness.

Suddenly, the universe was a garden, blooming with galaxies, with ours but a single bloom.

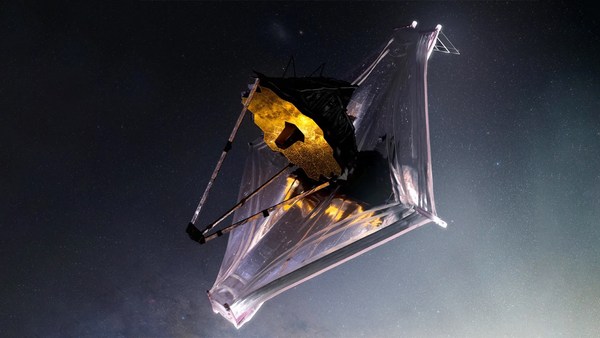

That same year, in another country, suspended between two World Wars, another young scientist came up with the radical idea of using rocket technology, this deadly military technology, to mount an enormous telescope and launch it into Earth's orbit. Not only closer to the stars, but bypassing the atmosphere that occludes our terrestrial instruments. It would take another two generations of scientists to make that telescope a reality: a shimmering poem of metal, physics and perseverance bearing Hubble's name.

But when the Hubble Space Telescope launched in 1990, our human fallibility had slipped into the precision of the instrument, and it turned out that its primary mirror was ground into the wrong spherical shape, warping these long-awaited images of the unfathomed universe. Up the coast from Mount Wilson Observatory, a teenage girl watched her father, who had worked on the Hubble, one of NASA's first Black engineers, come home brokenhearted. He didn't know that his observant daughter would become poet laureate of his country and would commemorate him in the tenderest tribute that an artist's daughter has ever composed for a scientist father, which would win her the Pulitzer Prize the year the Hubble's corrected optics captured that revolutionary, ultra-deep field image of the observable universe, revealing what neither Hubble nor Henrietta Leavitt could have imagined. That ours is not just one of several galaxies, but that there are 100 billion galaxies out there, each containing 100 billion stars.

Narrator: From “My God, It’s Full of Stars.”

When my father worked on the Hubble Telescope, he said

They operated like surgeons: scrubbed and sheathed

In papery green, the room a clean, cold and bright white.

He’d read Larry Niven at home, and drink scotch on the rocks,

His eyes exhausted and pink. These were the Reagan years,

When we lived with our finger on The Button and struggled

To view our enemies as children. My father spent whole seasons

Bowing before the oracle-eye, hungry for what it would find.

His face lit-up whenever anyone asked, and his arms would rise

As if he were weightless, perfectly at ease in the never-ending

Night of space. On the ground, we tied postcards to balloons

For peace. Prince Charles married Lady Di. Rock Hudson died.

We learned new words for things. The decade changed.

The first few pictures came back blurred, and I felt ashamed

For all the cheerful engineers, my father and his tribe. The second time,

The optics jibed. We saw to the edge of all there is --

So brutal and alive it seemed to comprehend us back.