June 2010. I landed for the first time in Rome, Italy. I wasn't there to sightsee. I was there to solve world hunger.

(Laughter)

That's right. I was a 25-year-old PhD student armed with a prototype tool developed back at my university, and I was going to help the World Food Programme fix hunger. So I strode into the headquarters building and my eyes scanned the row of UN flags, and I smiled as I thought to myself, "The engineer is here."

(Laughter)

Give me your data. I'm going to optimize everything.

(Laughter)

Tell me the food that you've purchased, tell me where it's going and when it needs to be there, and I'm going to tell you the shortest, fastest, cheapest, best set of routes to take for the food. We're going to save money, we're going to avoid delays and disruptions, and bottom line, we're going to save lives. You're welcome.

(Laughter)

I thought it was going to take 12 months, OK, maybe even 13. This is not quite how it panned out. Just a couple of months into the project, my French boss, he told me, "You know, Mallory, it's a good idea, but the data you need for your algorithms is not there. It's the right idea but at the wrong time, and the right idea at the wrong time is the wrong idea."

(Laughter)

Project over. I was crushed.

When I look back now on that first summer in Rome and I see how much has changed over the past six years, it is an absolute transformation. It's a coming of age for bringing data into the humanitarian world. It's exciting. It's inspiring. But we're not there yet. And brace yourself, executives, because I'm going to be putting companies on the hot seat to step up and play the role that I know they can.

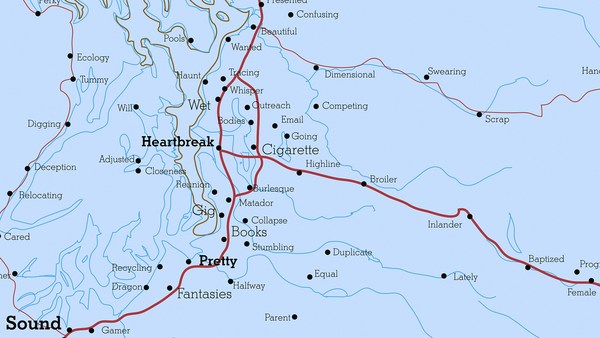

My experiences back in Rome prove using data you can save lives. OK, not that first attempt, but eventually we got there. Let me paint the picture for you. Imagine that you have to plan breakfast, lunch and dinner for 500,000 people, and you only have a certain budget to do it, say 6.5 million dollars per month. Well, what should you do? What's the best way to handle it? Should you buy rice, wheat, chickpea, oil? How much? It sounds simple. It's not. You have 30 possible foods, and you have to pick five of them. That's already over 140,000 different combinations. Then for each food that you pick, you need to decide how much you'll buy, where you're going to get it from, where you're going to store it, how long it's going to take to get there. You need to look at all of the different transportation routes as well. And that's already over 900 million options. If you considered each option for a single second, that would take you over 28 years to get through. 900 million options.

So we created a tool that allowed decisionmakers to weed through all 900 million options in just a matter of days. It turned out to be incredibly successful. In an operation in Iraq, we saved 17 percent of the costs, and this meant that you had the ability to feed an additional 80,000 people. It's all thanks to the use of data and modeling complex systems.

But we didn't do it alone. The unit that I worked with in Rome, they were unique. They believed in collaboration. They brought in the academic world. They brought in companies. And if we really want to make big changes in big problems like world hunger, we need everybody to the table. We need the data people from humanitarian organizations leading the way, and orchestrating just the right types of engagements with academics, with governments. And there's one group that's not being leveraged in the way that it should be. Did you guess it? Companies.

Companies have a major role to play in fixing the big problems in our world. I've been in the private sector for two years now. I've seen what companies can do, and I've seen what companies aren't doing, and I think there's three main ways that we can fill that gap: by donating data, by donating decision scientists and by donating technology to gather new sources of data. This is data philanthropy, and it's the future of corporate social responsibility. Bonus, it also makes good business sense.

Companies today, they collect mountains of data, so the first thing they can do is start donating that data. Some companies are already doing it. Take, for example, a major telecom company. They opened up their data in Senegal and the Ivory Coast and researchers discovered that if you look at the patterns in the pings to the cell phone towers, you can see where people are traveling. And that can tell you things like where malaria might spread, and you can make predictions with it. Or take for example an innovative satellite company. They opened up their data and donated it, and with that data you could track how droughts are impacting food production. With that you can actually trigger aid funding before a crisis can happen.

This is a great start. There's important insights just locked away in company data. And yes, you need to be very careful. You need to respect privacy concerns, for example by anonymizing the data.

But even if the floodgates opened up, and even if all companies donated their data to academics, to NGOs, to humanitarian organizations, it wouldn't be enough to harness that full impact of data for humanitarian goals. Why? To unlock insights in data, you need decision scientists. Decision scientists are people like me. They take the data, they clean it up, transform it and put it into a useful algorithm that's the best choice to address the business need at hand. In the world of humanitarian aid, there are very few decision scientists. Most of them work for companies. So that's the second thing that companies need to do. In addition to donating their data, they need to donate their decision scientists.

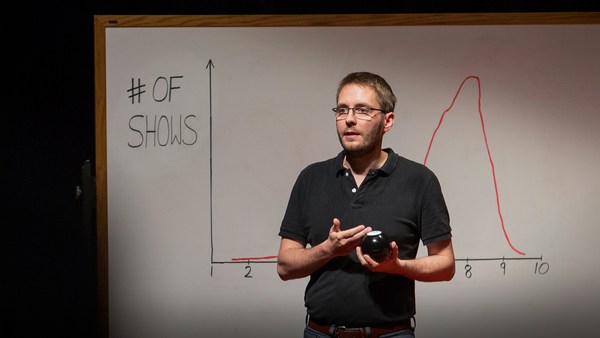

Now, companies will say, "Ah! Don't take our decision scientists from us. We need every spare second of their time." But there's a way. If a company was going to donate a block of a decision scientist's time, it would actually make more sense to spread out that block of time over a long period, say for example five years. This might only amount to a couple of hours per month, which a company would hardly miss, but what it enables is really important: long-term partnerships. Long-term partnerships allow you to build relationships, to get to know the data, to really understand it and to start to understand the needs and challenges that the humanitarian organization is facing. In Rome, at the World Food Programme, this took us five years to do, five years. That first three years, OK, that was just what we couldn't solve for. Then there was two years after that of refining and implementing the tool, like in the operations in Iraq and other countries. I don't think that's an unrealistic timeline when it comes to using data to make operational changes. It's an investment. It requires patience. But the types of results that can be produced are undeniable. In our case, it was the ability to feed tens of thousands more people.

So we have donating data, we have donating decision scientists, and there's actually a third way that companies can help: donating technology to capture new sources of data. You see, there's a lot of things we just don't have data on. Right now, Syrian refugees are flooding into Greece, and the UN refugee agency, they have their hands full. The current system for tracking people is paper and pencil, and what that means is that when a mother and her five children walk into the camp, headquarters is essentially blind to this moment. That's all going to change in the next few weeks, thanks to private sector collaboration. There's going to be a new system based on donated package tracking technology from the logistics company that I work for. With this new system, there will be a data trail, so you know exactly the moment when that mother and her children walk into the camp. And even more, you know if she's going to have supplies this month and the next. Information visibility drives efficiency. For companies, using technology to gather important data, it's like bread and butter. They've been doing it for years, and it's led to major operational efficiency improvements. Just try to imagine your favorite beverage company trying to plan their inventory and not knowing how many bottles were on the shelves. It's absurd. Data drives better decisions.

Now, if you're representing a company, and you're pragmatic and not just idealistic, you might be saying to yourself, "OK, this is all great, Mallory, but why should I want to be involved?" Well for one thing, beyond the good PR, humanitarian aid is a 24-billion-dollar sector, and there's over five billion people, maybe your next customers, that live in the developing world. Further, companies that are engaging in data philanthropy, they're finding new insights locked away in their data. Take, for example, a credit card company that's opened up a center that functions as a hub for academics, for NGOs and governments, all working together. They're looking at information in credit card swipes and using that to find insights about how households in India live, work, earn and spend. For the humanitarian world, this provides information about how you might bring people out of poverty. But for companies, it's providing insights about your customers and potential customers in India. It's a win all around. Now, for me, what I find exciting about data philanthropy -- donating data, donating decision scientists and donating technology -- it's what it means for young professionals like me who are choosing to work at companies. Studies show that the next generation of the workforce care about having their work make a bigger impact. We want to make a difference, and so through data philanthropy, companies can actually help engage and retain their decision scientists. And that's a big deal for a profession that's in high demand.

Data philanthropy makes good business sense, and it also can help revolutionize the humanitarian world. If we coordinated the planning and logistics across all of the major facets of a humanitarian operation, we could feed, clothe and shelter hundreds of thousands more people, and companies need to step up and play the role that I know they can in bringing about this revolution.

You've probably heard of the saying "food for thought." Well, this is literally thought for food. It finally is the right idea at the right time.

(Laughter)

Très magnifique.

Thank you.

(Applause)