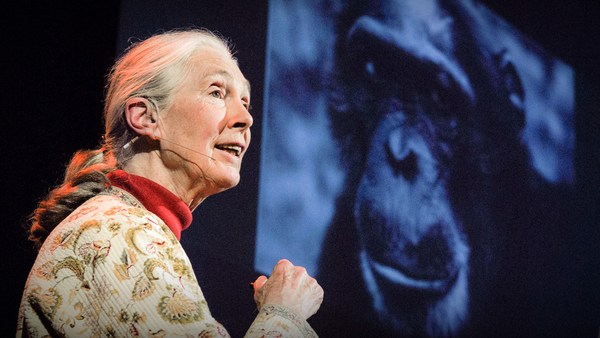

Who are we? That is the big question. And essentially we are just an upright-walking, big-brained, super-intelligent ape. This could be us. We belong to the family called the Hominidae. We are the species called Homo sapiens sapiens, and it's important to remember that, in terms of our place in the world today and our future on planet Earth.

We are one species of about five and a half thousand mammalian species that exist on planet Earth today. And that's just a tiny fraction of all species that have ever lived on the planet in past times. We're one species out of approximately, or let's say, at least 16 upright-walking apes that have existed over the past six to eight million years. But as far as we know, we're the only upright-walking ape that exists on planet Earth today, except for the bonobos.

And it's important to remember that, because the bonobos are so human, and they share 99 percent of their genes with us. And we share our origins with a handful of the living great apes. It's important to remember that we evolved. Now, I know that's a dirty word for some people, but we evolved from common ancestors with the gorillas, the chimpanzee and also the bonobos. We have a common past, and we have a common future. And it is important to remember that all of these great apes have come on as long and as interesting evolutionary journey as we ourselves have today. And it's this journey that is of such interest to humanity, and it's this journey that has been the focus of the past three generations of my family, as we've been in East Africa looking for the fossil remains of our ancestors to try and piece together our evolutionary past.

And this is how we look for them. A group of dedicated young men and women walk very slowly out across vast areas of Africa, looking for small fragments of bone, fossil bone, that may be on the surface. And that's an example of what we may do as we walk across the landscape in Northern Kenya, looking for fossils. I doubt many of you in the audience can see the fossil that's in this picture, but if you look very carefully, there is a jaw, a lower jaw, of a 4.1-million-year-old upright-walking ape as it was found at Lake Turkana on the west side. (Laughter) It's extremely time-consuming, labor-intensive and it is something that is going to involve a lot more people, to begin to piece together our past. We still really haven't got a very complete picture of it.

When we find a fossil, we mark it. Today, we've got great technology: we have GPS. We mark it with a GPS fix, and we also take a digital photograph of the specimen, so we could essentially put it back on the surface, exactly where we found it. And we can bring all this information into big GIS packages, today. When we then find something very important, like the bones of a human ancestor, we begin to excavate it extremely carefully and slowly, using dental picks and fine paintbrushes. And all the sediment is then put through these screens, and where we go again through it very carefully, looking for small bone fragments, and it's then washed.

And these things are so exciting. They are so often the only, or the very first time that anybody has ever seen the remains. And here's a very special moment, when my mother and myself were digging up some remains of human ancestors. And it is one of the most special things to ever do with your mother. (Laughter) Not many people can say that.

But now, let me take you back to Africa, two million years ago. I'd just like to point out, if you look at the map of Africa, it does actually look like a hominid skull in its shape. Now we're going to go to the East African and the Rift Valley. It essentially runs up from the Gulf of Aden, or runs down to Lake Malawi. And the Rift Valley is a depression. It's a basin, and rivers flow down from the highlands into the basin, carrying sediment, preserving the bones of animals that lived there.

If you want to become a fossil, you actually need to die somewhere where your bones will be rapidly buried. You then hope that the earth moves in such a way as to bring the bones back up to the surface. And then you hope that one of us lot will walk around and find small pieces of you. (Laughter) OK, so it is absolutely surprising that we know as much as we do know today about our ancestors, because it's incredibly difficult, A, for these things to become -- to be -- preserved, and secondly, for them to have been brought back up to the surface. And we really have only spent 50 years looking for these remains, and begin to actually piece together our evolutionary story.

So, let's go to Lake Turkana, which is one such lake basin in the very north of our country, Kenya. And if you look north here, there's a big river that flows into the lake that's been carrying sediment and preserving the remains of the animals that lived there. Fossil sites run up and down both lengths of that lake basin, which represents some 20,000 square miles. That's a huge job that we've got on our hands. Two million years ago at Lake Turkana, Homo erectus, one of our human ancestors, actually lived in this region. You can see some of the major fossil sites that we've been working in the north. But, essentially, two million years ago, Homo erectus, up in the far right corner, lived alongside three other species of human ancestor. And here is a skull of a Homo erectus, which I just pulled off the shelf there. (Laughter)

But it is not to say that being a single species on planet Earth is the norm. In fact, if you go back in time, it is the norm that there are multiple species of hominids or of human ancestors that coexist at any one time. Where did these things come from? That's what we're still trying to find answers to, and it is important to realize that there is diversity in all different species, and our ancestors are no exception. Here's some reconstructions of some of the fossils that have been found from Lake Turkana.

But I was very lucky to have been brought up in Kenya, essentially accompanying my parents to Lake Turkana in search of human remains. And we were able to dig up, when we got old enough, fossils such as this, a slender-snouted crocodile. And we dug up giant tortoises, and elephants and things like that. But when I was 12, as I was in this picture, a very exciting expedition was in place on the west side, when they found essentially the skeleton of this Homo erectus.

I could relate to this Homo erectus skeleton very well, because I was the same age that he was when he died. And I imagined him to be tall, dark-skinned. His brothers certainly were able to run long distances chasing prey, probably sweating heavily as they did so. He was very able to use stones effectively as tools. And this individual himself, this one that I'm holding up here, actually had a bad back. He'd probably had an injury as a child. He had a scoliosis and therefore must have been looked after quite carefully by other female, and probably much smaller, members of his family group, to have got to where he did in life, age 12. Unfortunately for him, he fell into a swamp and couldn't get out. Essentially, his bones were rapidly buried and beautifully preserved.

And he remained there until 1.6 million years later, when this very famous fossil hunter, Kamoya Kimeu, walked along a small hillside and found that small piece of his skull lying on the surface amongst the pebbles, recognized it as being hominid. It's actually this little piece up here on the top. Well, an excavation was begun immediately, and more and more little bits of skull started to be extracted from the sediment. And what was so fun about it was this: the skull pieces got closer and closer to the roots of the tree, and fairly recently the tree had grown up, but it had found that the skull had captured nice water in the hillside, and so it had decided to grow its roots in and around this, holding it in place and preventing it from washing away down the slope. We began to find limb bones; we found finger bones, the bones of the pelvis, vertebrae, ribs, the collar bones, things that had never, ever been seen before in Homo erectus. It was truly exciting. He had a body very similar to our own, and he was on the threshold of becoming human.

Well, shortly afterwards, members of his species started to move northwards out of Africa, and you start to see fossils of Homo erectus in Georgia, China and also in parts of Indonesia. So, Homo erectus was the first human ancestor to leave Africa and begin its spread across the globe. Some exciting finds, again, as I mentioned, from Dmanisi, in the Republic of Georgia. But also, surprising finds recently announced from the Island of Flores in Indonesia, where a group of these human ancestors have been isolated, and have become dwarfed, and they're only about a meter in height. But they lived only 18,000 years ago, and that is truly extraordinary to think about.

Just to put this in terms of generations, because people do find it hard to think of time, Homo erectus left Africa 90,000 generations ago. We evolved essentially from an African stock. Again, at about 200,000 years as a fully-fledged us. And we only left Africa about 70,000 years ago. And until 30,000 years ago, at least three upright-walking apes shared the planet Earth.

The question now is, well, who are we? We're certainly a polluting, wasteful, aggressive species, with a few nice things thrown in, perhaps. (Laughter) For the most part, we're not particularly pleasant at all. We have a much larger brain than our ape ancestors. Is this a good evolutionary adaptation, or is it going to lead us to being the shortest-lived hominid species on planet Earth?

And what is it that really makes us us? I think it's our collective intelligence. It's our ability to write things down, our language and our consciousness. From very primitive beginnings, with a very crude tool kit of stones, we now have a very advanced tool kit, and our tool use has really reached unprecedented levels: we've got buggies to Mars; we've mapped the human genome; and recently even created synthetic life, thanks to Craig Venter.

And we've also managed to communicate with people all over the world, from extraordinary places. Even from within an excavation in northern Kenya, we can talk to people about what we're doing. As Al Gore so clearly has reminded us, we have reached extraordinary numbers of people on this planet. Human ancestors really only survive on planet Earth, if you look at the fossil record, for about, on average, a million years at a time. We've only been around for the past 200,000 years as a species, yet we've reached a population of more than six and a half billion people.

And last year, our population grew by 80 million. I mean, these are extraordinary numbers. You can see here, again, taken from Al Gore's book. But what's happened is our technology has removed the checks and balances on our population growth. We have to control our numbers, and I think this is as important as anything else that's being done in the world today. But we have to control our numbers, because we can't really hold it together as a species.

My father so appropriately put it, that "We are certainly the only animal that makes conscious choices that are bad for our survival as a species." Can we hold it together? It's important to remember that we all evolved in Africa. We all have an African origin. We have a common past and we share a common future. Evolutionarily speaking, we're just a blip. We're sitting on the edge of a precipice, and we have the tools and the technology at our hands to communicate what needs to be done to hold it together today. We could tell every single human being out there, if we really wanted to. But will we do that, or will we just let nature take its course?

Well, to end on a very positive note, I think evolutionarily speaking, this is probably a fairly good thing, in the end. I'll leave it at that, thank you very much. (Applause)