Women are works of art. On the outside as on the inside. I am a neuroscientist, and I focus on the inside, especially on women's brains.

There are many theories on how women's brains differ from men's brains, and I've been looking at brains for 20 years and can guarantee that there is no such thing as a gendered brain. Pink and blue, Barbie and Lego, those are all inventions that have nothing to do with the way our brains are built.

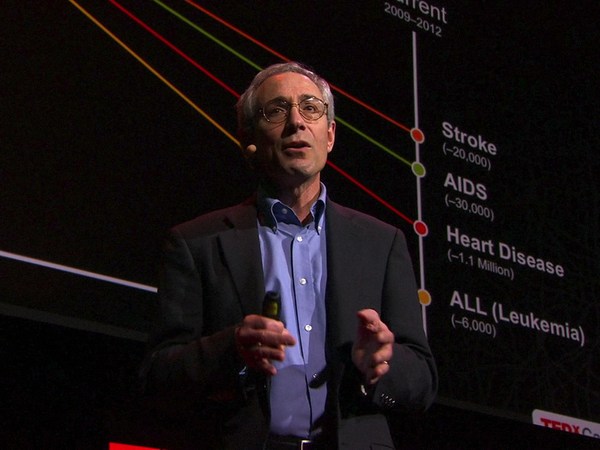

That said, women's brains differ from men's brains in some respects. And I'm here to talk about these differences, because they actually matter for our health. For example, women are more likely than men to be diagnosed with an anxiety disorder or depression, not to mention headaches and migraines. But also, at the core of my research, women are more likely than men to have Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimer's disease is the most common cause of dementia on the planet, affecting close to six million people in the United States alone. But almost two thirds of all those people are actually women. So for every man suffering from Alzheimer's there are two women. So why is that overall? Is it age? Is it lifespan? What else could it be?

A few years ago, I launched the Women's Brain Initiative at Weill Cornell Medicine in New York City, exactly to answer those questions. And tonight, I'm here with some answers.

So it turns out our brains age differently, and menopause plays a key role here for women. Now most people think of the brain as a kind of black box, isolated from the rest of the body. But in reality, our brains are in constant interaction with the rest of us. And perhaps surprisingly, the interactions with the reproductive system are crucial for brain aging in women. These interactions are mediated by our hormones. And we know that hormones differ between the genders.

Men have more testosterone, women have more estrogens. But what really matters here is that these hormones differ in their longevity. Men's testosterone doesn't run out until late in life, which is a slow and pretty much symptom-free process, of course.

(Laughter)

Women's estrogens, on the other hand, start fading in midlife, during menopause, which is anything but symptom-free. We associate menopause with the ovaries, but when women say that they're having hot flashes, night sweats, insomnia, memory lapses, depression, anxiety, those symptoms don't start in the ovaries. They start in the brain. Those are neurological symptoms. We're just not used to thinking about them as such. So why is that? Why are our brains impacted by menopause?

Well, first of all, our brains and ovaries are part of the neuroendocrine system. As part of the system, the brain talks to the ovaries and the ovaries talk back to the brain, every day of our lives as women. So the health of the ovaries is linked to the health of the brain. And the other way around. At the same time, hormones like estrogen are not only involved in reproduction, but also in brain function. And estrogen in particular, or estradiol, is really key for energy production in the brain.

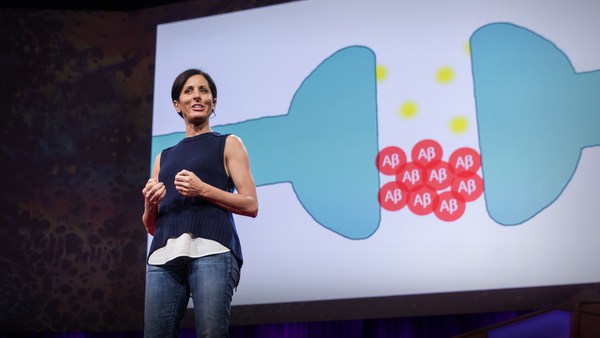

At the cellular level, estrogen literally pushes neurons to burn glucose to make energy. If your estrogen is high, your brain energy is high. When your estrogen declines though, your neurons start slowing down and age faster. And studies have shown that this process can even lead to the formation of amyloid plaques, or Alzheimer's plaques, which are a hallmark of Alzheimer's disease.

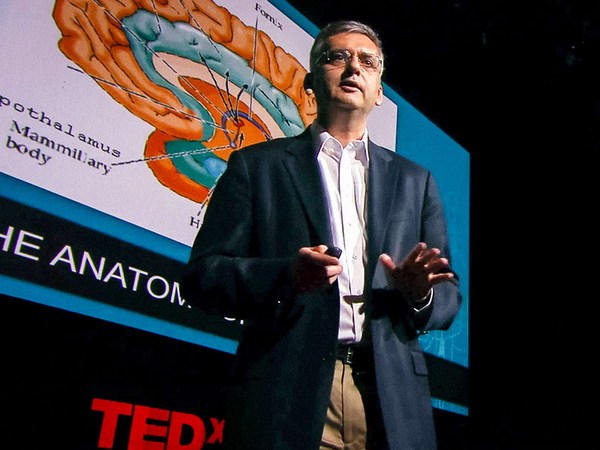

These effects are stronger in specific brain regions, starting with the hypothalamus, which is in charge of regulating body temperature. When estrogen doesn't activate the hypothalamus correctly, the brain cannot regulate body temperature correctly. So those hot flashes that women get, that's the hypothalamus. Then there's the brain stem, in charge of sleep and wake. When estrogen doesn't activate the brain stem correctly, we have trouble sleeping. Or it's the amygdala, the emotional center of the brain, close to the hippocampus, the memory center of the brain. When estrogen levels ebb in these regions, we start getting mood swings perhaps and forget things. So this is the brain anatomy of menopause, if you will.

But let me show you what an actual woman's brain can look like. So this is a kind of brain scan called positron emission tomography or PET. It looks at brain energy levels. And this is what you want your brain to look like when you're in your 40s. Really nice and bright. Now this brain belongs to a woman who was 43 years old when she was first scanned, before menopause. And this is the same brain just eight years later, after menopause. If we put them side by side, I think you can easily see how the bright yellow turned orange, almost purple. That's a 30 percent drop in brain energy levels.

Now in general, this just doesn't seem to happen to a man of the same age. In our studies with hundreds of people, we show that middle-aged men usually have high brain energy levels. For women, brain energy is usually fine before menopause, but then it gradually declines during the transition. And this was found independent of age. It didn't matter if the women were 40, 50 or 60. What mattered most was that they were in menopause.

So of course we need more research to confirm this, but it looks like women's brains in midlife are more sensitive to hormonal aging than just straight up chronological aging. And this is important information to have, because so many women can feel these changes. So many of our patients have said to me that they feel like their minds are playing tricks on them, to put it mildly. So I really want to validate this, because it's real. And so just to clarify, if this is you, you are not crazy.

(Laughter)

(Applause)

Thank you.

It's important. So many women have worried that they might be losing their minds. But the truth is that your brain might be going through a transition, or is going through a transition and needs time and support to adjust. Also, if anyone is concerned that middle-aged women might be underperformers, I'll just quickly add that we looked at cognitive performance, God forbid, right?

(Laughter)

Let's not do that. But we looked at cognitive performance, and we found absolutely no differences between men and women before and after menopause. And other studies confirm this. So basically, we may be tired, but we are just as sharp.

(Laughter)

Get that out of the way.

That all said, there is something else more serious that deserves our attention. If you remember, I mentioned that estrogen declines could potentially promote the formation of amyloid plaques, or Alzheimer's plaques. But there's another kind of brain scan that looks exactly at those plaques. And we used it to show that middle-aged men hardly have any, which is great. But for women, there's quite a bit of an increase during the transition to menopause. And I want to be really, really clear here that not all women develop the plaques, and not all women with the plaques develop dementia. Having the plaques is a risk factor, it is not in any way a diagnosis, especially at this stage.

But still, it's quite an insight to associate Alzheimer's with menopause. We think of menopause as belonging to middle age and Alzheimer's as belonging to old age. But in reality, many studies, including my own work, had shown that Alzheimer's disease starts with negative changes in the brain years, if not decades, prior to clinical symptoms. So for women, it looks like this process starts in midlife, during menopause. Which is important information to have, because it gives us a time line to start looking for those changes.

So in terms of a time line, most women go through menopause in their early 50s. But it can be earlier, often because of medical interventions. And the common example is a hysterectomy and/or an oophorectomy, which is the surgical removal of the uterus and/or the ovaries. And unfortunately, there is evidence that having the uterus and, more so, the ovaries removed prior to menopause correlates with the higher risk of dementia in women. And I know that this is upsetting news, and it's definitely depressing news, but we need to talk about it because most women are not aware of this correlation, and it seems like very important information to have.

Also, no one is suggesting that women decline these procedures if they need them. The point here is that we really need to better understand what happens to our brains as we go through menopause, natural or medical, and how to protect our brains in the process.

So how do we do that? How do we protect our brains? Should we take hormones? That's a fair question, it's a good question. And the shortest possible answer right now is that hormonal therapy can be helpful to alleviate a number of symptoms, like hot flashes, but it's not currently recommended for dementia prevention. And many of us are working on testing different formulations and different dosages and different time lines, and hopefully, all this work will lead to a change in recommendations in the future.

Meanwhile, there are other things that we can do today to support our hormones and their effects on the brain that do not require medications but do require taking a good look at our lifestyle. That's because the foods we eat, how much exercise we get, how much sleep we get or don't get, how much stress we have in our lives, those are all things that can actually impact our hormones -- for better and for worse.

Food, for example. There are many diets out there, but studies have shown that the Mediterranean diet in particular is supportive of women's health. Women on this diet have a much lower risk of cognitive decline, of depression, of heart disease, of stroke and of cancer, and they also have fewer hot flashes. What's interesting about this diet is that it's quite rich in foods that contain estrogens in the form of phytoestrogens or estrogens from plants that act like mild estrogens in our bodies. Some phytoestrogens have been linked to a possible risk of cancer, but not the ones in this diet, which are safe. Especially from flax seeds, sesame seeds, dried apricots, legumes and a number of fruits. And for some good news, dark chocolate contains phytoestrogens, too.

So diet is one way to gain estrogens, but it's just as important to avoid things that suppress our estrogens instead, especially stress. Stress can literally steal your estrogens, and that's because cortisol, which is the main stress hormone, works in balance with our estrogens. So if cortisol goes up, your estrogens go down. If cortisol goes down, your estrogens go back up. So reducing stress is really important. It doesn't just help your day, it also helps your brain.

So these are just a few things that we can do to support our brains and there are more. But the important thing here is that changing the way we understand the female brain really changes the way that we care for it, and the way that we frame women's health. And the more women demand this information, the sooner we'll be able to break the taboos around menopause, and also come up with solutions that actually work, not just for Alzheimer's disease, but for women's brain health as a whole. Brain health is women's health.

Thank you.

(Applause)

Thank you. Oh, thank you.