So I'm going to talk to you about you about the political chemistry of oil spills and why this is an incredibly important, long, oily, hot summer, and why we need to keep ourselves from getting distracted. But before I talk about the political chemistry, I actually need to talk about the chemistry of oil.

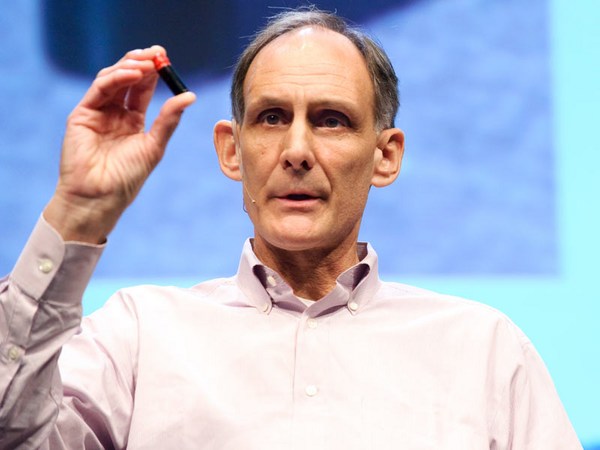

This is a photograph from when I visited Prudhoe Bay in Alaska in 2002 to watch the Minerals Management Service testing their ability to burn oil spills in ice. And what you see here is, you see a little bit of crude oil, you see some ice cubes, and you see two sandwich baggies of napalm. The napalm is burning there quite nicely. And the thing is, is that oil is really an abstraction for us as the American consumer. We're four percent of the world's population; we use 25 percent of the world's oil production. And we don't really understand what oil is, until you check out its molecules, And you don't really understand that until you see this stuff burn. So this is what happens as that burn gets going. It takes off. It's a big woosh. I highly recommend that you get a chance to see crude oil burn someday, because you will never need to hear another poli sci lecture on the geopolitics of oil again. It'll just bake your retinas. So there it is; the retinas are baking.

Let me tell you a little bit about this chemistry of oil. Oil is a stew of hydrocarbon molecules. It starts of with the very small ones, which are one carbon, four hydrogen -- that's methane -- it just floats off. Then there's all sorts of intermediate ones with middle amounts of carbon. You've probably heard of benzene rings; they're very carcinogenic. And it goes all the way over to these big, thick, galumphy ones that have hundreds of carbons, and they have thousands of hydrogens, and they have vanadium and heavy metals and sulfur and all kinds of craziness hanging off the sides of them. Those are called the asphaltenes; they're an ingredient in asphalt. They're very important in oil spills.

Let me tell you a little bit about the chemistry of oil in water. It is this chemistry that makes oil so disastrous. Oil doesn't sink, it floats. If it sank, it would be a whole different story as far as an oil spill. And the other thing it does is it spreads out the moment it hits the water. It spreads out to be really thin, so you have a hard time corralling it. The next thing that happens is the light ends evaporate, and some of the toxic things float into the water column and kill fish eggs and smaller fish and things like that, and shrimp. And then the asphaltenes -- and this is the crucial thing -- the asphaltenes get whipped by the waves into a frothy emulsion, something like mayonnaise. It triples the amount of oily, messy goo that you have in the water, and it makes it very hard to handle. It also makes it very viscous. When the Prestige sank off the coast of Spain, there were big, floating cushions the size of sofa cushions of emulsified oil, with the consistency, or the viscosity, of chewing gum. It's incredibly hard to clean up. And every single oil is different when it hits water.

When the chemistry of the oil and water also hits our politics, it's absolutely explosive. For the first time, American consumers will kind of see the oil supply chain in front of themselves. They have a "eureka!" moment, when we suddenly understand oil in a different context. So I'm going to talk just a little bit about the origin of these politics, because it's really crucial to understanding why this summer is so important, why we need to stay focused. Nobody gets up in the morning and thinks, "Wow! I'm going to go buy some three-carbon-to-12-carbon molecules to put in my tank and drive happily to work." No, they think, "Ugh. I have to go buy gas. I'm so angry about it. The oil companies are ripping me off. They set the prices, and I don't even know. I am helpless over this." And this is what happens to us at the gas pump -- and actually, gas pumps are specifically designed to diffuse that anger. You might notice that many gas pumps, including this one, are designed to look like ATMs. I've talked to engineers. That's specifically to diffuse our anger, because supposedly we feel good about ATMs. (Laughter) That shows you how bad it is.

But actually, I mean, this feeling of helplessness comes in because most Americans actually feel that oil prices are the result of a conspiracy, not of the vicissitudes of the world oil market. And the thing is, too, is that we also feel very helpless about the amount that we consume, which is somewhat reasonable, because in fact, we have designed this system where, if you want to get a job, it's much more important to have a car that runs, to have a job and keep a job, than to have a GED. And that's actually very perverse.

Now there's another perverse thing about the way we buy gas, which is that we'd rather be doing anything else. This is BP's gas station in downtown Los Angeles. It is green. It is a shrine to greenishness. "Now," you think, "why would something so lame work on people so smart?" Well, the reason is, is because, when we're buying gas, we're very invested in this sort of cognitive dissonance. I mean, we're angry at the one hand and we want to be somewhere else. We don't want to be buying oil; we want to be doing something green. And we get kind of in on our own con. I mean -- and this is funny, it looks funny here. But in fact, that's why the slogan "beyond petroleum" worked. But it's an inherent part of our energy policy, which is we don't talk about reducing the amount of oil that we use. We talk about energy independence. We talk about hydrogen cars. We talk about biofuels that haven't been invented yet. And so, cognitive dissonance is part and parcel of the way that we deal with oil, and it's really important to dealing with this oil spill.

Okay, so the politics of oil are very moral in the United States. The oil industry is like a huge, gigantic octopus of engineering and finance and everything else, but we actually see it in very moral terms. This is an early-on photograph -- you can see, we had these gushers. Early journalists looked at these spills, and they said, "This is a filthy industry." But they also saw in it that people were getting rich for doing nothing. They weren't farmers, they were just getting rich for stuff coming out of the ground. It's the "Beverly Hillbillies," basically. But in the beginning, this was seen as a very morally problematic thing, long before it became funny.

And then, of course, there was John D. Rockefeller. And the thing about John D. is that he went into this chaotic wild-east of oil industry, and he rationalized it into a vertically integrated company, a multinational. It was terrifying; you think Walmart is a terrifying business model now, imagine what this looked like in the 1860s or 1870s. And it also the kind of root of how we see oil as a conspiracy. But what's really amazing is that Ida Tarbell, the journalist, went in and did a big exposé of Rockefeller and actually got the whole antitrust laws put in place. But in many ways, that image of the conspiracy still sticks with us. And here's one of the things that Ida Tarbell said -- she said, "He has a thin nose like a thorn. There were no lips. There were puffs under the little colorless eyes with creases running from them." (Laughter) Okay, so that guy is actually still with us. (Laughter) I mean, this is a very pervasive -- this is part of our DNA. And then there's this guy, okay.

So, you might be wondering why it is that, every time we have high oil prices or an oil spill, we call these CEOs down to Washington, and we sort of pepper them with questions in public and we try to shame them. And this is something that we've been doing since 1974, when we first asked them, "Why are there these obscene profits?" And we've sort of personalized the whole oil industry into these CEOs. And we take it as, you know -- we look at it on a moral level, rather than looking at it on a legal and financial level. And so I'm not saying these guys aren't liable to answer questions -- I'm just saying that, when you focus on whether they are or are not a bunch of greedy bastards, you don't actually get around to the point of making laws that are either going to either change the way they operate, or you're going to get around to really reducing the amount of oil and reducing our dependence on oil. So I'm saying this is kind of a distraction. But it makes for good theater, and it's powerfully cathartic as you probably saw last week.

So the thing about water oil spills is that they are very politically galvanizing. I mean, these pictures -- this is from the Santa Barbara spill. You have these pictures of birds. They really influence people. When the Santa Barbara spill happened in 1969, it formed the environmental movement in its modern form. It started Earth Day. It also put in place the National Environmental Policy Act, the Clean Air Act, the Clean Water Act. Everything that we are really stemmed from this period. I think it's important to kind of look at these pictures of the birds and understand what happens to us. Here we are normally; we're standing at the gas pump, and we're feeling kind of helpless. We look at these pictures and we understand, for the first time, our role in this supply chain. We connect the dots in the supply chain. And we have this kind of -- as voters, we have kind of a "eureka!" moment. This is why these moments of these oil spills are so important. But it's also really important that we don't get distracted by the theater or the morals of it. We actually need to go in and work on the roots of the problem.

One of the things that happened with the two previous oil spills was that we really worked on some of the symptoms. We were very reactive, as opposed to being proactive about what happened. And so what we did was, actually, we made moratoriums on the east and west coasts on drilling. We stopped drilling in ANWR, but we didn't actually reduce the amount of oil that we consumed. In fact, it's continued to increase. The only thing that really reduces the amount of oil that we consume is much higher prices. As you can see, our own production has fallen off as our reservoirs have gotten old and expensive to drill out. We only have two percent of the world's oil reserves; 65 percent of them are in the Persian Gulf.

One of the things that's happened because of this is that, since 1969, the country of Nigeria, or the part of Nigeria that pumps oil, which is the delta -- which is two times the size of Maryland -- has had thousands of oil spills a year. I mean, we've essentially been exporting oil spills when we import oil from places without tight environmental regulations. That has been the equivalent of an Exxon Valdez spill every year since 1969. And we can wrap our heads around the spills, because that's what we see here, but in fact, these guys actually live in a war zone. There's a thousand battle-related deaths a year in this area twice the size of Maryland, and it's all related to the oil. And these guys, I mean, if they were in the U.S., they might be actually here in this room. They have degrees in political science, degrees in business -- they're entrepreneurs. They don't actually want to be doing what they're doing. And it's sort of one of the other groups of people who pay a price for us.

The other thing that we've done, as we've continued to increase demand, is that we kind of play a shell game with the costs. One of the places we put in a big oil project in Chad, with Exxon. So the U.S. taxpayer paid for it; the World Bank, Exxon paid for it. We put it in. There was a tremendous banditry problem. I was there in 2003. We were driving along this dark, dark road, and the guy in the green stepped out, and I was just like, "Ahhh! This is it." And then the guy in the Exxon uniform stepped out, and we realized it was okay. They have their own private sort of army around them at the oil fields. But at the same time, Chad has become much more unstable, and we are not paying for that price at the pump. We pay for it in our taxes on April 15th.

We do the same thing with the price of policing the Persian Gulf and keeping the shipping lanes open. This is 1988 -- we actually bombed two Iranian oil platforms that year. That was the beginning of an escalating U.S. involvement there that we do not pay for at the pump. We pay for it on April 15th, and we can't even calculate the cost of this involvement. The other place that is sort of supporting our dependence on oil and our increased consumption is the Gulf of Mexico, which was not part of the moratoriums. Now what's happened in the Gulf of Mexico -- as you can see, this is the Minerals Management diagram of wells for gas and oil. It's become this intense industrialized zone. It doesn't have the same resonance for us that the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge has, but it should, I mean, it's a bird sanctuary. Also, every time you buy gasoline in the United States, half of it is actually being refined along the coast, because the Gulf actually has about 50 percent of our refining capacity and a lot of our marine terminals as well. So the people of the Gulf have essentially been subsidizing the rest of us through a less-clean environment.

And finally, American families also pay a price for oil. Now on the one hand, the price at the pump is not really very high when you consider the actual cost of the oil, but on the other hand, the fact that people have no other transit options means that they pay a large amount of their income into just getting back and forth to work, generally in a fairly crummy car. If you look at people who make $50,000 a year, they have two kids, they might have three jobs or more, and then they have to really commute. They're actually spending more on their car and fuel than they are on taxes or on health care. And the same thing happens at the 50th percentile, around 80,000. Gasoline costs are a tremendous drain on the American economy, but they're also a drain on individual families and it's kind of terrifying to think about what happens when prices get higher.

So, what I'm going to talk to you about now is: what do we have to do this time? What are the laws? What do we have to do to keep ourselves focused? One thing is -- we need to stay away from the theater. We need to stay away from the moratoriums. We need to focus really back again on the molecules. The moratoriums are fine, but we do need to focus on the molecules on the oil. One of the things that we also need to do, is we need to try to not kind of fool ourselves into thinking that you can have a green world, before you reduce the amount of oil that we use. We need to focus on reducing the oil.

What you see in this top drawing is a schematic of how petroleum gets used in the U.S. economy. It comes in on the side -- the useful stuff is the dark gray, and the un-useful stuff, which is called the rejected energy -- the waste, goes up to the top. Now you can see that the waste far outweighs the actually useful amount. And one of the things that we need to do is, not only fix the fuel efficiency of our vehicles and make them much more efficient, but we also need to fix the economy in general.

We need to remove the perverse incentives to use more fuel. For example, we have an insurance system where the person who drives 20,000 miles a year pays the same insurance as somebody who drives 3,000. We actually encourage people to drive more. We have policies that reward sprawl -- we have all kinds of policies. We need to have more mobility choices. We need to make the gas price better reflect the real cost of oil. And we need to shift subsidies from the oil industry, which is at least 10 billion dollars a year, into something that allows middle-class people to find better ways to commute. Whether that's getting a much more efficient car and also kind of building markets for new cars and new fuels down the road, this is where we need to be. We need to kind of rationalize this whole thing, and you can find more about this policy. It's called STRONG, which is "Secure Transportation Reducing Oil Needs Gradually," and the idea is instead of being helpless, we need to be more strong. They're up at NewAmerica.net. What's important about these is that we try to move from feeling helpless at the pump, to actually being active and to really sort of thinking about who we are, having kind of that special moment, where we connect the dots actually at the pump.

Now supposedly, oil taxes are the third rail of American politics -- the no-fly zone. I actually -- I agree that a dollar a gallon on oil is probably too much, but I think that if we started this year with three cents a gallon on gasoline, and upped it to six cents next year, nine cents the following year, all the way up to 30 cents by 2020, that we could actually significantly reduce our gasoline consumption, and at the same time we would give people time to prepare, time to respond, and we would be raising money and raising consciousness at the same time. Let me give you a little sense of how this would work.

This is a gas receipt, hypothetically, for a year from now. The first thing that you have on the tax is -- you have a tax for a stronger America -- 33 cents. So you're not helpless at the pump. And the second thing that you have is a kind of warning sign, very similar to what you would find on a cigarette pack. And what it says is, "The National Academy of Sciences estimates that every gallon of gas you burn in your car creates 29 cents in health care costs." That's a lot. And so this -- you can see that you're paying considerably less than the health care costs on the tax. And also, the hope is that you start to be connected to the whole greater system. And at the same time, you have a number that you can call to get more information on commuting, or a low-interest loan on a different kind of car, or whatever it is you're going to need to actually reduce your gasoline dependence. With this whole sort of suite of policies, we could actually reduce our gasoline consumption -- or our oil consumption -- by 20 percent by 2020. So, three million barrels a day.

But in order to do this, one of the things we really need to do, is we need to remember we are people of the hydrocarbon. We need to keep or minds on the molecules and not get distracted by the theater, not get distracted by the cognitive dissonance of the green possibilities that are out there. We need to kind of get down and do the gritty work of reducing our dependence upon this fuel and these molecules.

Thank you.

(Applause)