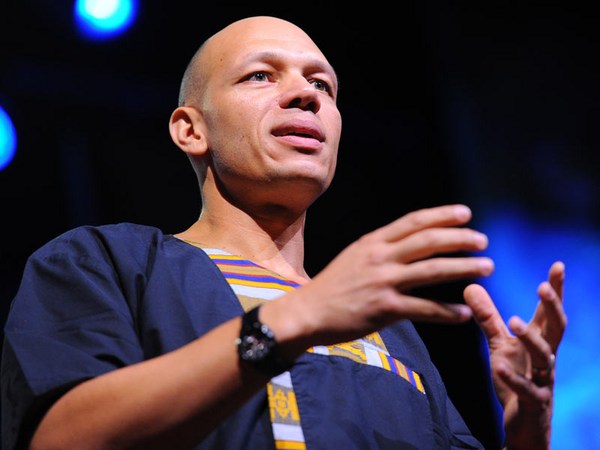

I was 14 years old in 1994 when my country, South Africa, held its historic first democratic elections. I can vividly remember my mother taking me with her to the voting station, which was near the clinic where she worked, and where she would cast her vote for the very first time in a general election at the age of 45 years old. That's two years older than I am today, standing in front of you.

By then, my mother was a taxpayer and a home owner, and she was a mother of four children. She was a university graduate who had a long and storied career behind her in South Africa's public health service. She had raised us and educated us and imbued in all of us the religious and cultural traditions of our ancestors. In other words, she was a fully-fledged adult woman of 45 years old. But she had never been allowed to vote in an election before because she was also Black.

Take a moment to think about what that day and that election must have meant for her and for the millions of Black South Africans who were voting for the very first time. People who were previously not even considered legitimate citizens in the country of their birth.

It took five long years of negotiations for the multiracial, multiparty Convention for a Democratic South Africa, and later for the first democratic parliament, to negotiate, draft and pass one of the world’s most respected and celebrated constitutions. For years, that negotiation process was marred by sabotage, assassinations, boycotts and bloodshed. And yet, despite these many challenges, it also delivered a functioning electoral process and a visionary blueprint for a transformed society in South Africa. This blueprint contained not just a bill of rights, but a bill of public goods, a promissory note and a commitment to deliver a demonstrably better life for all of South Africa's people.

In the decades since, however, that promise has not adequately been kept, largely because of the failure of our political leaders to live up to the promise of the country's hard-won transition. These failures have led many young people today to express their preference for an authoritarian path, believing that gaining access to their most basic needs is worth sacrificing the right to vote and to participate in democratic governance. But history and research have shown us that democracy is still worth fighting for despite the inadequacies of its leaders. And so, to get South Africa to a place where democracy can thrive, we need a revolution in political leadership. This has become my life's work.

South Africa's constitution is widely considered to be one of the most unique constitutions around the world. This is primarily because we have a bill of rights, which both declares our freedoms and guarantees our right to access things such as health care, water, education, housing, a protected and sustainable environment, and nutrition and shelter for children. Not many states have codified the right to access specific government services into their supreme law. Some of these rights are absolute, including the rights to basic education, while others, such as the right to housing, water, food, health care and social security, are considered progressively realizable rights. This means that the constitution places an obligation on all governments, regardless of political affiliation and regardless of the promises contained in their political manifestos, to implement measures that will lead to the full realization of these rights. This is why I say our bill of rights is also a bill of public goods.

But the South Africa that young people live in today is also one of the most unequal societies on Earth. The South Africa of young people today is one of prolonged energy and water shortages that render life undignified and intolerable. It is a country mired in institutionalized corruption at the very highest levels. It is a country whose education outcomes are so poor that our fourth-grade learners have the worst reading ability in the world: 81 percent are incapable of reading for meaning. Our constitution may guarantee our rights, but poor leadership has hindered our ability to access those rights. And as a result, the country’s most vulnerable citizens have lost faith in the promise of South African democracy. So much so that in a 2021 study by the Pan-African, non-partisan research network Afrobarometer, two-thirds of South Africans said that they would be willing to give up elections if a non-elected government could provide them with guaranteed security, housing and jobs. 46 percent of the survey respondents said that they would be very willing to do so. That’s nearly half. And the highest levels of support for this proposal were amongst younger and more educated respondents.

The disillusionment with democracy in South Africa is also borne out by statistics from our electoral commission, which point to a sustained decline in voter participation numbers, particularly amongst young people in South Africa. Part of that may be because anybody under the age of 35 in South Africa has only ever experienced life in a democratic society. And to them, that society is simply not that visionary nation of ethical leaders delivering a society based on social justice and fundamental human rights. And so they feel no motivation to fight for a democracy that doesn't actually deliver on its promises. I desperately want that to change before South Africa slips into an authoritarian trap.

I first ran for elected political office in 2008, at the age of 28, hoping to right these very wrongs. I wanted to contribute to the high-minded and constitutionally enshrined idea of South Africa. A country of triumph over diversity, a place which had put the injustices of the past so far behind it, that education, health care, water and safety were considered basic human rights. In 2009, I was elected into a national assembly and to which I was one of the youngest members of parliament. But by then the contagion of corruption had already begun to infiltrate the political class, and its consequences -- the declining quality of service delivery, the rapid decay of public infrastructure, the communities neglected and the tensions inflamed -- were increasingly visible in daily life. I resigned from active politics at the beginning of my second term, burned out, frustrated and disillusioned by how easily hubris, corruption and incompetence could stifle the country's socioeconomic progress. But even at my most jaded, I understood that the challenge lay with the quality of leaders in political office, not with the system in which they were duty bound to serve.

And so today, my work is focused on building capacity in the right leaders, people of integrity, community mindedness, skill, self awareness, and to help them to make the transition into political and government leadership roles in South Africa and also throughout the African continent. I started an organization called Futurelect to do just this, with a special emphasis on programs that support women to run for elected political office and occupy senior, influential and impactful roles in our democracies. We do this not only because it's fair and just for women to have equal representation in political life, but also because countless studies about diversity and leadership have shown that when more women are around the decision-making table, progress towards objectives improves dramatically. The very same is true of political leadership. So at Futurelect, we bring together classes of young people and women leaders who come from a range of political and ideological traditions, some having no political affiliation at all, to help shape the quality of leadership on the continent for the future.

My experience in politics strengthened my belief that values, character and purpose in our leaders matter far more than the ideology and political persuasion. So the values that we amplify at Futurelect, the ones we expect our fellows to embody, include a commitment to democratic governance, a belief in the equality and legitimacy of all people, the pursuit of policy based on evidence, not prejudice, and a keen awareness that political leadership is, first and foremost, about people, not prestige or position. We're building a community of ethical leaders from around the country, the region and the continent. Young people and women who can hold each other accountable based on shared values, and who can model a different kind of leadership in a world which is drunk with polarization and hopelessly entrenched political views. The time that our fellows spend developing their leadership abilities also enables them to stress-test their positions amongst people who share their values but may not share their politics. And also to articulate a vision for their leadership in government and the public sector. Our graduates have run for office in elections, some successfully and some not. Those who have been unsuccessful are retooling their strategies and preparing to contest again. Their resilience inspires me. Our graduates are also political appointees in local, state-level and national-level administrations. They work with cabinet ministers, mayors, governors and one in their country's presidency.

At the same time, I'm also committed to fortifying young South Africans' belief in democracy's power and potential. So we are also investing in active citizenship by creating freely available online learning tools to support new generations of young citizens and young voters to show up in between elections, demand accountability from their public representatives, participate robustly in the governance of their country, and ultimately to see themselves as part of the fabric of our democratic system.

Autocratic political entrepreneurs are very fond of claiming that you cannot eat a constitution or that democracy does not put food on the table. This has been proven time and time again to be untrue. But our ability to demonstrate that is tragically diminished when we elect leaders who lack the commitment, the integrity and the ability to deliver on the massive potential of democratic government. When we recognize that no political leader or party in any democracy has a monopoly on good governance, we can hold all leaders accountable for the values-based fundamentals that ensure all governments truly represent the interests of the people who elected them. And when leaders of integrity and purpose come together across political lines, even in the most heightened and dangerous of circumstances, we know that they are capable of crafting laws and building systems that reflect and reinforce our very highest aspirations.

Constitutions can feed us. Democracies can provide us with shelter and safety, but only if we take active responsibility for them and elect leaders who can deliver on democracy's extraordinary potential.

Thank you.

(Applause)