So today I want to talk to you about something that has been at the core of my existence for the past years: freedom and democracy.

I was elected mayor of Caracas, the capital of Venezuela, in the year 2000. I was reelected in the year 2004. And then in the year 2008, when I was running for higher office, I was banned to run for office. Because we were going to win. At that time, we started a movement, a nonviolent civil resistance grassroots movement that went all over Venezuela and worked with people all around the country to build a network that could face off the dictatorship of Nicolás Maduro.

In the year 2013, Maduro was elected. He stole an election. And in January of 2014, we called for protest. Tens of thousands of people went to the streets. And that took me to prison. I spent the next seven years in imprisonment, four of them in solitary confinement in a military prison.

The history of my country, Venezuela, is one, like many other Latin American countries, African countries, one of military rule, exile, imprisonment and politics. So I had read a lot about what it meant to be in prison. I read the usual suspects, I read about Mandela, I read about Gandhi, I read about my [role] model, Martin Luther King. But I also read a lot about the experience of Venezuelans, including my great grandfather, who had been a political prisoner for years and died in exile. Everything that they had to say was relevant to their own condition, but they all spoke about the importance of having a routine. So I had my own routine since day one, February 18 of 2014.

My routine was simple. I would do three things every day. I would pray to take care of my soul. I would read, write, to do something with my mind. And I would do exercise. I did those three things with Spartan discipline every day. If I did them, I would feel that I was winning the day.

But there was one thing that I would think about every single day: why I was in prison. And in fact, this is something that I'm sure happens to all prisoners, political prisoners or not. That's what prison, in a way, is made for. So every day I thought about what freedom and democracy meant. And it was there in a cell, two by two, in solitary confinement that I really got to understand what freedom was. And it became clear to me that freedom is not about one thing. In fact, freedom is about the possibility of doing many things. So the possibility to speak out, to express your mind. It's the possibility to move around in your country. It's the possibility to assemble with whomever you want to assemble, to pray to whomever you want to pray, to own property. And all of those things were taken away from me and from millions of Venezuelans. And it also became very clear to me that freedom and democracy were two sides of a coin. Were interdependent. You cannot have freedom without democracy. You cannot have democracy if people are not free.

So that took me to think about the state of democracy. In fact, next month, in November, we're going to celebrate the 35th anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall, 35 years. Back then, I was in grad school. It was the '90s. And I remember the excitement that was everywhere about spreading democracy, spreading freedom, human rights, all over the place. I remember my teachers going to different countries with students. But when we look back 35 years ago and we fast forward, things didn't really come out the way it was expected. Only 10 years ago, 42 percent of the world's population was living under autocratic rule. That was 3.1 billion people. That's around the same time I was sent to prison. Today, 72 percent of the global population is living under some sort of autocratic rule.

So let's think about this. This is 5.7 billion people in the world that don't have the rights that most people in this room have. They can't speak freely, they can't move freely, they can't pray freely, they can't own property. 5.7 billion people in the world.

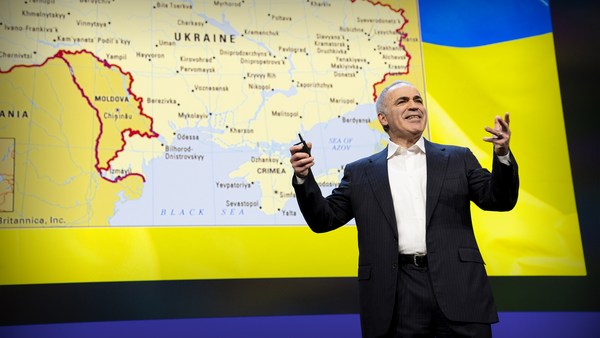

After seven years of imprisonment, I was able to escape prison and went into exile. Exile is another form of imprisonment. At the beginning, it was tough. But then I started to meet other people like myself, who had been leading protests in their countries, who had been political prisoners, who were in exile. And we were very different in any way we could think about: our skin color, our religion, our languages, the story of our families, the history of our countries. We were very different. But when we spoke about what it meant to fight for freedom and to confront autocracies, I was with my buddies. It was the same people, the same movement. So we decided to create an alliance of democracy defenders and freedom fighters. So alongside with Garry Kasparov, from Russia, and an incredible woman from Iran, Masih Alinejad, we decided to create an alliance of freedom fighters and democracy defenders. And that's how we created the World Liberty Congress, which is an alliance of hundreds of leaders, many of them you have seen their work in Hong Kong, in Russia, in Belarus, in Uganda, in Zimbabwe, in Afghanistan, in Cambodia, Nicaragua, Cuba, in many countries. And we decided to work together, to come together with a single purpose: to stop autocracy and to bring democracy to our countries. But it became very clear to us that we were not only facing our local autocrat, we were also facing a network of autocrats, an axis of autocrats. And this is something that might not be obvious to many people. But in fact, autocrats work together. They support each other. In many ways: diplomatically, financially, militarily, through their kleptocratic networks. And this is not an ideological alliance. It has nothing to do with ideology. Right, left, conservative, liberals, nothing to do with that. It has to do with power, money and a common enemy: democracy.

So that's why you have the nationalists from Russia, the theocrats from Iran, the communists from China, working together under a similar alliance.

So if autocrats are working together and the world is coming to a point where 72 percent of the world's population is under autocracy, it's time to think about why should you care about this? Why should everybody, anybody care about this? Why should someone who’s living in the United States or in Europe or in a functioning democracy care about this? Well, if you care about climate change, if you care about gender equality, if you care about women's rights, if you care about human rights, if you care about corruption, if you care about migration, you need to be concerned about the rise of autocracy and the need for democracy. 30 percent of the CO2 emissions come from China and Russia alone. 80 percent of the world’s poverty comes from autocratic countries. 90 percent of the forced migration, and we from Venezuela can speak about this, has at its root cause autocracy. So we need to care about this.

And what can be done? What can be done about this? Well, I believe that we are now at a moment where we need to make a tipping point of the engagement of people around the world to create a movement towards freedom and democracy. Think about the climate change movement 20, 30, 40 years ago. It was not mainstream. It was there, but it was not mainstream. But then what happened? Researchers, governments, policymakers, activists, artists, school teachers, students, children, everybody came together under the same cause. Because I remember during the 1980s, '90s, you would look up to the sky and you would think that there was an ozone hole in the sky that was going to destroy. So the threat was very clear. People came together, policy came together, and now it's mainstream. Things are being done. I believe we are at that point with respect to democracy and freedom. If that trend continues, today 72 percent, if that trend continues, maybe in the next 25 years, in 2050, the entire world would be autocratic. And that is less than a generation ago. So we must take action.

What can we do? Well, the first thing I believe is to assume that we need to take the offensive. Stop legitimizing autocrats. Autocrats today are comfortable. They do business with governments, with businesses. We need to think of smart sanctions, of ways to make them accountable for the violations of human rights.

Second, there needs to be a support for pro-democracy and freedom movements. In the United States, that is the most actively philanthropic society in the world, only two percent of philanthropy goes to democracy-related issues. Only two percent. And a fraction of a fraction of that two percent goes to promote democracy outside the US. It's not a priority. So supporting pro-democracy movements, supporting the people that want to be free, should be a priority for all. And I mean, let me give you some examples. Technology. Access to internet, to free and uncensored internet. Think of the potential transformational capacity to give people all over the world access to internet. Let me give you another example. Using new technologies like Bitcoin to promote and support the potential of these movements. We are doing this already. In the case of Venezuela, we supported more than 80,000 medical doctors and nurses using Stablecoins and Bitcoins because under autocracies you are under a financial apartheid. Give opportunities for training. Give opportunities for these movements to be part of a global conversation.

And finally, we need to build a global movement. There is not one person, one organization, one government, that can do this by themselves. Similar to climate change. We need to think of this challenge as a network. We need to create nodes of network, nodes of network that activate all over the place. We need to activate anyone with the things that they can do. Musicians should think about singing for freedom. Artists, intellectuals, researchers, activists, governments. Everybody can create their own node with a similar goal, which is freedom and democracy.

When I was in solitary confinement, I had a window, and I could see through the crack of that window that there was a tree, and in that tree there was a hawk. And I contemplated that animal for hours and hours and hours. I only think that you contemplate an animal that long if you're in biology or you're in prison. And one day, a guard told me, because I was always telling the guards about the hawk, he said, "You know, the hawk is injured, went through barbed wire, and he’s injured.” And I said, "Bring it to me." And to my surprise, they brought it to me. Maybe because they thought it was going to die. I fed that hawk. And that's the hawk in my cell. That's a drawing I made of the prison I was [in], of that tree and of the hawk. And then one day, after a couple of months, they came to my cell, they threw a blanket on the hawk, they took it away. Of course it affected me. But less than a day after, that hawk was in the same tree. And it reassured me that it doesn't matter how low you are, how low percentage possibilities you have to succeed, there is always possibility to do so. So I came out and being in exile, I met a tattoo artist, that put me a tattoo of Venezuela on my leg, so I now have that eagle here, and I have it always with me.

(Applause)

As a reminder, as a reminder that we can always rise up to all of the challenges. So I ask all of you to stand up, to speak out, to do something about our freedom. This is our time. Think of 25 years, and let's give our children a free world with human rights, democracy and respect for all. Thank you very much, thank you very much.

(Cheers and applause)

Thank you.

(Cheers and applause continue)

Helen Walters: Thank you, thank you, Leo.

Audience: Venezuela libre!

Leopoldo Lopez: Venezuela libre, hermano, Venezuela libre.

HW: OK, Leo, I wanted to ask you a few questions, and actually Venezuela is one of them. So there were elections in July, Maduro says he won the election, observers says he did not. But what are you hearing? What is the situation in Venezuela right now?

LL: Well, so let me explain this very briefly. The case of Venezuela has been an electoral autocracy. So we've gone to elections for years. And we've been developing the ways in which we can know exactly the results. On July 28, there was an election, we had a candidate, Maria Corina Machado, she was disqualified the same way I was disqualified years ago. So we had another candidate, Edmundo González. He was unknown three months before the election, but he became known by everybody. And on the 28th of July, he won with 70 percent of the vote. The decision of Maduro was to steal the election. But we were able to prove with elements of every single voting machine, that we actually won. Maduro decided to have a repression all over the country. We went to the election with 300 political prisoners. Now there are maybe 2,500 political prisoners. I wake up every day to get a message from someone from my movement who has been taken to prison, That's the situation now. But I can assure you that we will be free. Because one thing is to think that you are a majority, and a very different one is to know. Everybody knows that we are a huge majority, and that will not be sustainable for Maduro because we will never surrender. And we will be free.

(Cheers and applause)

HW: OK, so we were just chatting backstage and you mentioned that today is a very special day, and I want to bring up a photo. And I wonder if you can tell us what today is for you.

LL: Well, today is the fourth anniversary of me meeting my family. This is my family, that’s my wife, Lilian, more than my half. You know, people say "my second half." No, no, it's just three quarters of who I am, my beautiful wife, Lilian. And these are my three kids, Manuela, who is now 15, Leo, who is 11 and Federica, who is one. And I had not seen them for almost two years. I had not seen my kids and my wife. And that’s the day, exactly four years ago, after I escaped, I met them back in Spain. So it's an important day for us. And I’m very grateful that Lilian is the woman who’s the mother of my kids. Because she was an incredible mother while I was away, and she was an incredible advocate for the freedom of all political prisoners when I was in prison.

HW: Leo, you’re an icon.

Thank you, Leo Lopez.

LL: Thank you very much.