I want to start my talk today with two observations about the human species. The first observation is something that you might think is quite obvious, and that's that our species, Homo sapiens, is actually really, really smart -- like, ridiculously smart -- like you're all doing things that no other species on the planet does right now. And this is, of course, not the first time you've probably recognized this. Of course, in addition to being smart, we're also an extremely vain species. So we like pointing out the fact that we're smart. You know, so I could turn to pretty much any sage from Shakespeare to Stephen Colbert to point out things like the fact that we're noble in reason and infinite in faculties and just kind of awesome-er than anything else on the planet when it comes to all things cerebral.

But of course, there's a second observation about the human species that I want to focus on a little bit more, and that's the fact that even though we're actually really smart, sometimes uniquely smart, we can also be incredibly, incredibly dumb when it comes to some aspects of our decision making. Now I'm seeing lots of smirks out there. Don't worry, I'm not going to call anyone in particular out on any aspects of your own mistakes. But of course, just in the last two years we see these unprecedented examples of human ineptitude. And we've watched as the tools we uniquely make to pull the resources out of our environment kind of just blow up in our face. We've watched the financial markets that we uniquely create -- these markets that were supposed to be foolproof -- we've watched them kind of collapse before our eyes.

But both of these two embarrassing examples, I think, don't highlight what I think is most embarrassing about the mistakes that humans make, which is that we'd like to think that the mistakes we make are really just the result of a couple bad apples or a couple really sort of FAIL Blog-worthy decisions. But it turns out, what social scientists are actually learning is that most of us, when put in certain contexts, will actually make very specific mistakes. The errors we make are actually predictable. We make them again and again. And they're actually immune to lots of evidence. When we get negative feedback, we still, the next time we're face with a certain context, tend to make the same errors. And so this has been a real puzzle to me as a sort of scholar of human nature. What I'm most curious about is, how is a species that's as smart as we are capable of such bad and such consistent errors all the time?

You know, we're the smartest thing out there, why can't we figure this out? In some sense, where do our mistakes really come from? And having thought about this a little bit, I see a couple different possibilities. One possibility is, in some sense, it's not really our fault. Because we're a smart species, we can actually create all kinds of environments that are super, super complicated, sometimes too complicated for us to even actually understand, even though we've actually created them. We create financial markets that are super complex. We create mortgage terms that we can't actually deal with. And of course, if we are put in environments where we can't deal with it, in some sense makes sense that we actually might mess certain things up. If this was the case, we'd have a really easy solution to the problem of human error. We'd actually just say, okay, let's figure out the kinds of technologies we can't deal with, the kinds of environments that are bad -- get rid of those, design things better, and we should be the noble species that we expect ourselves to be.

But there's another possibility that I find a little bit more worrying, which is, maybe it's not our environments that are messed up. Maybe it's actually us that's designed badly. This is a hint that I've gotten from watching the ways that social scientists have learned about human errors. And what we see is that people tend to keep making errors exactly the same way, over and over again. It feels like we might almost just be built to make errors in certain ways. This is a possibility that I worry a little bit more about, because, if it's us that's messed up, it's not actually clear how we go about dealing with it. We might just have to accept the fact that we're error prone and try to design things around it.

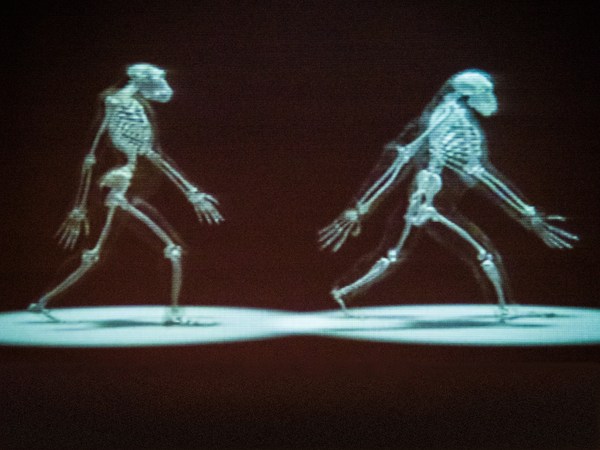

So this is the question my students and I wanted to get at. How can we tell the difference between possibility one and possibility two? What we need is a population that's basically smart, can make lots of decisions, but doesn't have access to any of the systems we have, any of the things that might mess us up -- no human technology, human culture, maybe even not human language. And so this is why we turned to these guys here. These are one of the guys I work with. This is a brown capuchin monkey. These guys are New World primates, which means they broke off from the human branch about 35 million years ago. This means that your great, great, great great, great, great -- with about five million "greats" in there -- grandmother was probably the same great, great, great, great grandmother with five million "greats" in there as Holly up here. You know, so you can take comfort in the fact that this guy up here is a really really distant, but albeit evolutionary, relative. The good news about Holly though is that she doesn't actually have the same kinds of technologies we do. You know, she's a smart, very cut creature, a primate as well, but she lacks all the stuff we think might be messing us up. So she's the perfect test case.

What if we put Holly into the same context as humans? Does she make the same mistakes as us? Does she not learn from them? And so on. And so this is the kind of thing we decided to do. My students and I got very excited about this a few years ago. We said, all right, let's, you know, throw so problems at Holly, see if she messes these things up. First problem is just, well, where should we start? Because, you know, it's great for us, but bad for humans. We make a lot of mistakes in a lot of different contexts. You know, where are we actually going to start with this? And because we started this work around the time of the financial collapse, around the time when foreclosures were hitting the news, we said, hhmm, maybe we should actually start in the financial domain. Maybe we should look at monkey's economic decisions and try to see if they do the same kinds of dumb things that we do.

Of course, that's when we hit a sort second problem -- a little bit more methodological -- which is that, maybe you guys don't know, but monkeys don't actually use money. I know, you haven't met them. But this is why, you know, they're not in the queue behind you at the grocery store or the ATM -- you know, they don't do this stuff. So now we faced, you know, a little bit of a problem here. How are we actually going to ask monkeys about money if they don't actually use it? So we said, well, maybe we should just, actually just suck it up and teach monkeys how to use money. So that's just what we did. What you're looking at over here is actually the first unit that I know of of non-human currency. We weren't very creative at the time we started these studies, so we just called it a token. But this is the unit of currency that we've taught our monkeys at Yale to actually use with humans, to actually buy different pieces of food. It doesn't look like much -- in fact, it isn't like much.

Like most of our money, it's just a piece of metal. As those of you who've taken currencies home from your trip know, once you get home, it's actually pretty useless. It was useless to the monkeys at first before they realized what they could do with it. When we first gave it to them in their enclosures, they actually kind of picked them up, looked at them. They were these kind of weird things. But very quickly, the monkeys realized that they could actually hand these tokens over to different humans in the lab for some food. And so you see one of our monkeys, Mayday, up here doing this. This is A and B are kind of the points where she's sort of a little bit curious about these things -- doesn't know. There's this waiting hand from a human experimenter, and Mayday quickly figures out, apparently the human wants this. Hands it over, and then gets some food. It turns out not just Mayday, all of our monkeys get good at trading tokens with human salesman. So here's just a quick video of what this looks like. Here's Mayday. She's going to be trading a token for some food and waiting happily and getting her food. Here's Felix, I think. He's our alpha male; he's a kind of big guy. But he too waits patiently, gets his food and goes on.

So the monkeys get really good at this. They're surprisingly good at this with very little training. We just allowed them to pick this up on their own. The question is: is this anything like human money? Is this a market at all, or did we just do a weird psychologist's trick by getting monkeys to do something, looking smart, but not really being smart. And so we said, well, what would the monkeys spontaneously do if this was really their currency, if they were really using it like money? Well, you might actually imagine them to do all the kinds of smart things that humans do when they start exchanging money with each other. You might have them start paying attention to price, paying attention to how much they buy -- sort of keeping track of their monkey token, as it were. Do the monkeys do anything like this?

And so our monkey marketplace was born. The way this works is that our monkeys normally live in a kind of big zoo social enclosure. When they get a hankering for some treats, we actually allowed them a way out into a little smaller enclosure where they could enter the market. Upon entering the market -- it was actually a much more fun market for the monkeys than most human markets because, as the monkeys entered the door of the market, a human would give them a big wallet full of tokens so they could actually trade the tokens with one of these two guys here -- two different possible human salesmen that they could actually buy stuff from. The salesmen were students from my lab. They dressed differently; they were different people. And over time, they did basically the same thing so the monkeys could learn, you know, who sold what at what price -- you know, who was reliable, who wasn't, and so on. And you can see that each of the experimenters is actually holding up a little, yellow food dish. and that's what the monkey can for a single token. So everything costs one token, but as you can see, sometimes tokens buy more than others, sometimes more grapes than others.

So I'll show you a quick video of what this marketplace actually looks like. Here's a monkey-eye-view. Monkeys are shorter, so it's a little short. But here's Honey. She's waiting for the market to open a little impatiently. All of a sudden the market opens. Here's her choice: one grapes or two grapes. You can see Honey, very good market economist, goes with the guy who gives more. She could teach our financial advisers a few things or two. So not just Honey, most of the monkeys went with guys who had more. Most of the monkeys went with guys who had better food. When we introduced sales, we saw the monkeys paid attention to that. They really cared about their monkey token dollar. The more surprising thing was that when we collaborated with economists to actually look at the monkeys' data using economic tools, they basically matched, not just qualitatively, but quantitatively with what we saw humans doing in a real market. So much so that, if you saw the monkeys' numbers, you couldn't tell whether they came from a monkey or a human in the same market.

And what we'd really thought we'd done is like we'd actually introduced something that, at least for the monkeys and us, works like a real financial currency. Question is: do the monkeys start messing up in the same ways we do? Well, we already saw anecdotally a couple of signs that they might. One thing we never saw in the monkey marketplace was any evidence of saving -- you know, just like our own species. The monkeys entered the market, spent their entire budget and then went back to everyone else. The other thing we also spontaneously saw, embarrassingly enough, is spontaneous evidence of larceny. The monkeys would rip-off the tokens at every available opportunity -- from each other, often from us -- you know, things we didn't necessarily think we were introducing, but things we spontaneously saw.

So we said, this looks bad. Can we actually see if the monkeys are doing exactly the same dumb things as humans do? One possibility is just kind of let the monkey financial system play out, you know, see if they start calling us for bailouts in a few years. We were a little impatient so we wanted to sort of speed things up a bit. So we said, let's actually give the monkeys the same kinds of problems that humans tend to get wrong in certain kinds of economic challenges, or certain kinds of economic experiments. And so, since the best way to see how people go wrong is to actually do it yourself, I'm going to give you guys a quick experiment to sort of watch your own financial intuitions in action.

So imagine that right now I handed each and every one of you a thousand U.S. dollars -- so 10 crisp hundred dollar bills. Take these, put it in your wallet and spend a second thinking about what you're going to do with it. Because it's yours now; you can buy whatever you want. Donate it, take it, and so on. Sounds great, but you get one more choice to earn a little bit more money. And here's your choice: you can either be risky, in which case I'm going to flip one of these monkey tokens. If it comes up heads, you're going to get a thousand dollars more. If it comes up tails, you get nothing. So it's a chance to get more, but it's pretty risky. Your other option is a bit safe. Your just going to get some money for sure. I'm just going to give you 500 bucks. You can stick it in your wallet and use it immediately. So see what your intuition is here. Most people actually go with the play-it-safe option. Most people say, why should I be risky when I can get 1,500 dollars for sure? This seems like a good bet. I'm going to go with that. You might say, eh, that's not really irrational. People are a little risk-averse. So what?

Well, the "so what?" comes when start thinking about the same problem set up just a little bit differently. So now imagine that I give each and every one of you 2,000 dollars -- 20 crisp hundred dollar bills. Now you can buy double to stuff you were going to get before. Think about how you'd feel sticking it in your wallet. And now imagine that I have you make another choice But this time, it's a little bit worse. Now, you're going to be deciding how you're going to lose money, but you're going to get the same choice. You can either take a risky loss -- so I'll flip a coin. If it comes up heads, you're going to actually lose a lot. If it comes up tails, you lose nothing, you're fine, get to keep the whole thing -- or you could play it safe, which means you have to reach back into your wallet and give me five of those $100 bills, for certain.

And I'm seeing a lot of furrowed brows out there. So maybe you're having the same intuitions as the subjects that were actually tested in this, which is when presented with these options, people don't choose to play it safe. They actually tend to go a little risky. The reason this is irrational is that we've given people in both situations the same choice. It's a 50/50 shot of a thousand or 2,000, or just 1,500 dollars with certainty. But people's intuitions about how much risk to take varies depending on where they started with.

So what's going on? Well, it turns out that this seems to be the result of at least two biases that we have at the psychological level. One is that we have a really hard time thinking in absolute terms. You really have to do work to figure out, well, one option's a thousand, 2,000; one is 1,500. Instead, we find it very easy to think in very relative terms as options change from one time to another. So we think of things as, "Oh, I'm going to get more," or "Oh, I'm going to get less." This is all well and good, except that changes in different directions actually effect whether or not we think options are good or not. And this leads to the second bias, which economists have called loss aversion.

The idea is that we really hate it when things go into the red. We really hate it when we have to lose out on some money. And this means that sometimes we'll actually switch our preferences to avoid this. What you saw in that last scenario is that subjects get risky because they want the small shot that there won't be any loss. That means when we're in a risk mindset -- excuse me, when we're in a loss mindset, we actually become more risky, which can actually be really worrying. These kinds of things play out in lots of bad ways in humans. They're why stock investors hold onto losing stocks longer -- because they're evaluating them in relative terms. They're why people in the housing market refused to sell their house -- because they don't want to sell at a loss.

The question we were interested in is whether the monkeys show the same biases. If we set up those same scenarios in our little monkey market, would they do the same thing as people? And so this is what we did, we gave the monkeys choices between guys who were safe -- they did the same thing every time -- or guys who were risky -- they did things differently half the time. And then we gave them options that were bonuses -- like you guys did in the first scenario -- so they actually have a chance more, or pieces where they were experiencing losses -- they actually thought they were going to get more than they really got.

And so this is what this looks like. We introduced the monkeys to two new monkey salesmen. The guy on the left and right both start with one piece of grape, so it looks pretty good. But they're going to give the monkeys bonuses. The guy on the left is a safe bonus. All the time, he adds one, to give the monkeys two. The guy on the right is actually a risky bonus. Sometimes the monkeys get no bonus -- so this is a bonus of zero. Sometimes the monkeys get two extra. For a big bonus, now they get three. But this is the same choice you guys just faced. Do the monkeys actually want to play it safe and then go with the guy who's going to do the same thing on every trial, or do they want to be risky and try to get a risky, but big, bonus, but risk the possibility of getting no bonus. People here played it safe. Turns out, the monkeys play it safe too. Qualitatively and quantitatively, they choose exactly the same way as people, when tested in the same thing.

You might say, well, maybe the monkeys just don't like risk. Maybe we should see how they do with losses. And so we ran a second version of this. Now, the monkeys meet two guys who aren't giving them bonuses; they're actually giving them less than they expect. So they look like they're starting out with a big amount. These are three grapes; the monkey's really psyched for this. But now they learn these guys are going to give them less than they expect. They guy on the left is a safe loss. Every single time, he's going to take one of these away and give the monkeys just two. the guy on the right is the risky loss. Sometimes he gives no loss, so the monkeys are really psyched, but sometimes he actually gives a big loss, taking away two to give the monkeys only one.

And so what do the monkeys do? Again, same choice; they can play it safe for always getting two grapes every single time, or they can take a risky bet and choose between one and three. The remarkable thing to us is that, when you give monkeys this choice, they do the same irrational thing that people do. They actually become more risky depending on how the experimenters started. This is crazy because it suggests that the monkeys too are evaluating things in relative terms and actually treating losses differently than they treat gains.

So what does all of this mean? Well, what we've shown is that, first of all, we can actually give the monkeys a financial currency, and they do very similar things with it. They do some of the smart things we do, some of the kind of not so nice things we do, like steal it and so on. But they also do some of the irrational things we do. They systematically get things wrong and in the same ways that we do. This is the first take-home message of the Talk, which is that if you saw the beginning of this and you thought, oh, I'm totally going to go home and hire a capuchin monkey financial adviser. They're way cuter than the one at ... you know -- Don't do that; they're probably going to be just as dumb as the human one you already have. So, you know, a little bad -- Sorry, sorry, sorry. A little bad for monkey investors.

But of course, you know, the reason you're laughing is bad for humans too. Because we've answered the question we started out with. We wanted to know where these kinds of errors came from. And we started with the hope that maybe we can sort of tweak our financial institutions, tweak our technologies to make ourselves better. But what we've learn is that these biases might be a deeper part of us than that. In fact, they might be due to the very nature of our evolutionary history. You know, maybe it's not just humans at the right side of this chain that's duncey. Maybe it's sort of duncey all the way back. And this, if we believe the capuchin monkey results, means that these duncey strategies might be 35 million years old. That's a long time for a strategy to potentially get changed around -- really, really old.

What do we know about other old strategies like this? Well, one thing we know is that they tend to be really hard to overcome. You know, think of our evolutionary predilection for eating sweet things, fatty things like cheesecake. You can't just shut that off. You can't just look at the dessert cart as say, "No, no, no. That looks disgusting to me." We're just built differently. We're going to perceive it as a good thing to go after. My guess is that the same thing is going to be true when humans are perceiving different financial decisions. When you're watching your stocks plummet into the red, when you're watching your house price go down, you're not going to be able to see that in anything but old evolutionary terms. This means that the biases that lead investors to do badly, that lead to the foreclosure crisis are going to be really hard to overcome.

So that's the bad news. The question is: is there any good news? I'm supposed to be up here telling you the good news. Well, the good news, I think, is what I started with at the beginning of the Talk, which is that humans are not only smart; we're really inspirationally smart to the rest of the animals in the biological kingdom. We're so good at overcoming our biological limitations -- you know, I flew over here in an airplane. I didn't have to try to flap my wings. I'm wearing contact lenses now so that I can see all of you. I don't have to rely on my own near-sightedness. We actually have all of these cases where we overcome our biological limitations through technology and other means, seemingly pretty easily. But we have to recognize that we have those limitations.

And here's the rub. It was Camus who once said that, "Man is the only species who refuses to be what he really is." But the irony is that it might only be in recognizing our limitations that we can really actually overcome them. The hope is that you all will think about your limitations, not necessarily as unovercomable, but to recognize them, accept them and then use the world of design to actually figure them out. That might be the only way that we will really be able to achieve our own human potential and really be the noble species we hope to all be.

Thank you.

(Applause)