Well, I'm an ocean chemist. I look at the chemistry of the ocean today. I look at the chemistry of the ocean in the past. The way I look back in the past is by using the fossilized remains of deepwater corals. You can see an image of one of these corals behind me. It was collected from close to Antarctica, thousands of meters below the sea, so, very different than the kinds of corals you may have been lucky enough to see if you've had a tropical holiday.

So I'm hoping that this talk will give you a four-dimensional view of the ocean. Two dimensions, such as this beautiful two-dimensional image of the sea surface temperature. This was taken using satellite, so it's got tremendous spatial resolution. The overall features are extremely easy to understand. The equatorial regions are warm because there's more sunlight. The polar regions are cold because there's less sunlight. And that allows big icecaps to build up on Antarctica and up in the Northern Hemisphere. If you plunge deep into the sea, or even put your toes in the sea, you know it gets colder as you go down, and that's mostly because the deep waters that fill the abyss of the ocean come from the cold polar regions where the waters are dense.

If we travel back in time 20,000 years ago, the earth looked very much different. And I've just given you a cartoon version of one of the major differences you would have seen if you went back that long. The icecaps were much bigger. They covered lots of the continent, and they extended out over the ocean. Sea level was 120 meters lower. Carbon dioxide [levels] were very much lower than they are today. So the earth was probably about three to five degrees colder overall, and much, much colder in the polar regions.

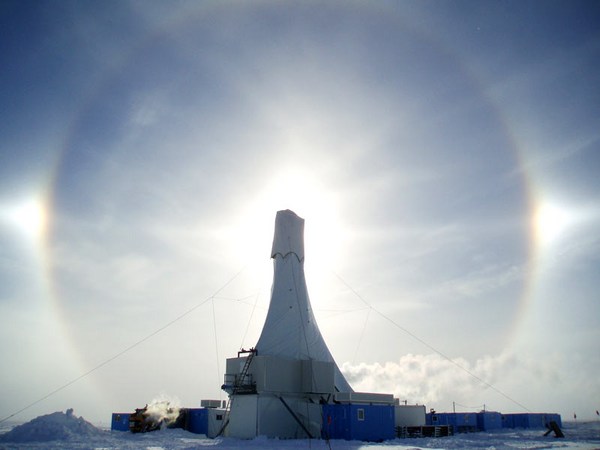

What I'm trying to understand, and what other colleagues of mine are trying to understand, is how we moved from that cold climate condition to the warm climate condition that we enjoy today. We know from ice core research that the transition from these cold conditions to warm conditions wasn't smooth, as you might predict from the slow increase in solar radiation. And we know this from ice cores, because if you drill down into ice, you find annual bands of ice, and you can see this in the iceberg. You can see those blue-white layers. Gases are trapped in the ice cores, so we can measure CO2 -- that's why we know CO2 was lower in the past -- and the chemistry of the ice also tells us about temperature in the polar regions. And if you move in time from 20,000 years ago to the modern day, you see that temperature increased. It didn't increase smoothly. Sometimes it increased very rapidly, then there was a plateau, then it increased rapidly. It was different in the two polar regions, and CO2 also increased in jumps.

So we're pretty sure the ocean has a lot to do with this. The ocean stores huge amounts of carbon, about 60 times more than is in the atmosphere. It also acts to transport heat across the equator, and the ocean is full of nutrients and it controls primary productivity.

So if we want to find out what's going on down in the deep sea, we really need to get down there, see what's there and start to explore. This is some spectacular footage coming from a seamount about a kilometer deep in international waters in the equatorial Atlantic, far from land. You're amongst the first people to see this bit of the seafloor, along with my research team. You're probably seeing new species. We don't know. You'd have to collect the samples and do some very intense taxonomy. You can see beautiful bubblegum corals. There are brittle stars growing on these corals. Those are things that look like tentacles coming out of corals. There are corals made of different forms of calcium carbonate growing off the basalt of this massive undersea mountain, and the dark sort of stuff, those are fossilized corals, and we're going to talk a little more about those as we travel back in time.

To do that, we need to charter a research boat. This is the James Cook, an ocean-class research vessel moored up in Tenerife. Looks beautiful, right? Great, if you're not a great mariner. Sometimes it looks a little more like this. This is us trying to make sure that we don't lose precious samples. Everyone's scurrying around, and I get terribly seasick, so it's not always a lot of fun, but overall it is.

So we've got to become a really good mapper to do this. You don't see that kind of spectacular coral abundance everywhere. It is global and it is deep, but we need to really find the right places. We just saw a global map, and overlaid was our cruise passage from last year. This was a seven-week cruise, and this is us, having made our own maps of about 75,000 square kilometers of the seafloor in seven weeks, but that's only a tiny fraction of the seafloor. We're traveling from west to east, over part of the ocean that would look featureless on a big-scale map, but actually some of these mountains are as big as Everest. So with the maps that we make on board, we get about 100-meter resolution, enough to pick out areas to deploy our equipment, but not enough to see very much. To do that, we need to fly remotely-operated vehicles about five meters off the seafloor. And if we do that, we can get maps that are one-meter resolution down thousands of meters. Here is a remotely-operated vehicle, a research-grade vehicle. You can see an array of big lights on the top. There are high-definition cameras, manipulator arms, and lots of little boxes and things to put your samples.

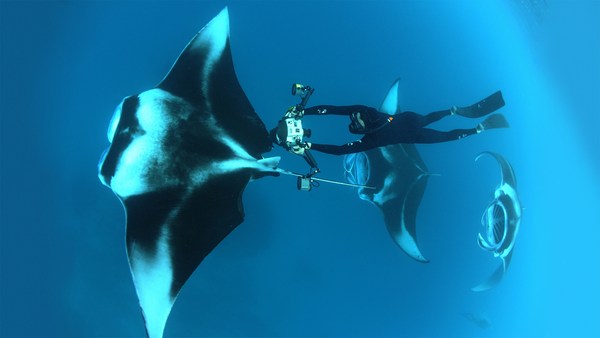

Here we are on our first dive of this particular cruise, plunging down into the ocean. We go pretty fast to make sure the remotely operated vehicles are not affected by any other ships. And we go down, and these are the kinds of things you see. These are deep sea sponges, meter scale. This is a swimming holothurian -- it's a small sea slug, basically. This is slowed down. Most of the footage I'm showing you is speeded up, because all of this takes a lot of time. This is a beautiful holothurian as well. And this animal you're going to see coming up was a big surprise. I've never seen anything like this and it took us all a bit surprised. This was after about 15 hours of work and we were all a bit trigger-happy, and suddenly this giant sea monster started rolling past. It's called a pyrosome or colonial tunicate, if you like. This wasn't what we were looking for. We were looking for corals, deep sea corals. You're going to see a picture of one in a moment. It's small, about five centimeters high. It's made of calcium carbonate, so you can see its tentacles there, moving in the ocean currents. An organism like this probably lives for about a hundred years. And as it grows, it takes in chemicals from the ocean. And the chemicals, or the amount of chemicals, depends on the temperature; it depends on the pH, it depends on the nutrients. And if we can understand how these chemicals get into the skeleton, we can then go back, collect fossil specimens, and reconstruct what the ocean used to look like in the past. And here you can see us collecting that coral with a vacuum system, and we put it into a sampling container. We can do this very carefully, I should add.

Some of these organisms live even longer. This is a black coral called Leiopathes, an image taken by my colleague, Brendan Roark, about 500 meters below Hawaii. Four thousand years is a long time. If you take a branch from one of these corals and polish it up, this is about 100 microns across. And Brendan took some analyses across this coral -- you can see the marks -- and he's been able to show that these are actual annual bands, so even at 500 meters deep in the ocean, corals can record seasonal changes, which is pretty spectacular.

But 4,000 years is not enough to get us back to our last glacial maximum. So what do we do? We go in for these fossil specimens. This is what makes me really unpopular with my research team. So going along, there's giant sharks everywhere, there are pyrosomes, there are swimming holothurians, there's giant sponges, but I make everyone go down to these dead fossil areas and spend ages kind of shoveling around on the seafloor. And we pick up all these corals, bring them back, we sort them out. But each one of these is a different age, and if we can find out how old they are and then we can measure those chemical signals, this helps us to find out what's been going on in the ocean in the past.

So on the left-hand image here, I've taken a slice through a coral, polished it very carefully and taken an optical image. On the right-hand side, we've taken that same piece of coral, put it in a nuclear reactor, induced fission, and every time there's some decay, you can see that marked out in the coral, so we can see the uranium distribution. Why are we doing this? Uranium is a very poorly regarded element, but I love it. The decay helps us find out about the rates and dates of what's going on in the ocean. And if you remember from the beginning, that's what we want to get at when we're thinking about climate. So we use a laser to analyze uranium and one of its daughter products, thorium, in these corals, and that tells us exactly how old the fossils are.

This beautiful animation of the Southern Ocean I'm just going to use illustrate how we're using these corals to get at some of the ancient ocean feedbacks. You can see the density of the surface water in this animation by Ryan Abernathey. It's just one year of data, but you can see how dynamic the Southern Ocean is. The intense mixing, particularly the Drake Passage, which is shown by the box, is really one of the strongest currents in the world coming through here, flowing from west to east. It's very turbulently mixed, because it's moving over those great big undersea mountains, and this allows CO2 and heat to exchange with the atmosphere in and out. And essentially, the oceans are breathing through the Southern Ocean. We've collected corals from back and forth across this Antarctic passage, and we've found quite a surprising thing from my uranium dating: the corals migrated from south to north during this transition from the glacial to the interglacial. We don't really know why, but we think it's something to do with the food source and maybe the oxygen in the water.

So here we are. I'm going to illustrate what I think we've found about climate from those corals in the Southern Ocean. We went up and down sea mountains. We collected little fossil corals. This is my illustration of that. We think back in the glacial, from the analysis we've made in the corals, that the deep part of the Southern Ocean was very rich in carbon, and there was a low-density layer sitting on top. That stops carbon dioxide coming out of the ocean. We then found corals that are of an intermediate age, and they show us that the ocean mixed partway through that climate transition. That allows carbon to come out of the deep ocean. And then if we analyze corals closer to the modern day, or indeed if we go down there today anyway and measure the chemistry of the corals, we see that we move to a position where carbon can exchange in and out. So this is the way we can use fossil corals to help us learn about the environment.

So I want to leave you with this last slide. It's just a still taken out of that first piece of footage that I showed you. This is a spectacular coral garden. We didn't even expect to find things this beautiful. It's thousands of meters deep. There are new species. It's just a beautiful place. There are fossils in amongst, and now I've trained you to appreciate the fossil corals that are down there.

So next time you're lucky enough to fly over the ocean or sail over the ocean, just think -- there are massive sea mountains down there that nobody's ever seen before, and there are beautiful corals.

Thank you.

(Applause)