Helen Walters: So, Chris, who's up first?

Chris Anderson: Well, we have a man who's worried about pandemics pretty much his whole life. He played an absolutely key role, more than 40 years ago, in helping the world get rid of the scourge of smallpox. And in 2006, he came to TED to warn the world of the dire risk of a global pandemic, and what we might do about it. So please welcome here Dr. Larry Brilliant. Larry, so good to see you.

Larry Brilliant: Thank you, nice to see you.

CA: Larry, in that talk, you showed a video clip that was a simulation of what a pandemic might look like. I would like to play it -- this gave me chills.

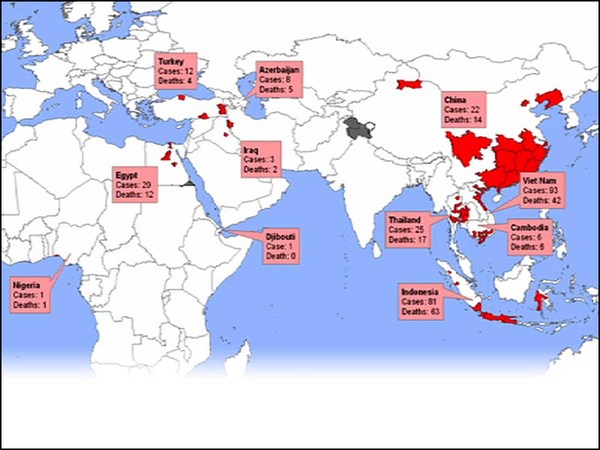

Larry Brilliant (TED2006): Let me show you a simulation of what a pandemic looks like, so we know what we're talking about. Let's assume, for example, that the first case occurs in South Asia. It initially goes quite slowly, you get two or three discrete locations. Then there will be secondary outbreaks. And the disease will spread from country to country so fast that you won't know what hit you. Within three weeks, it will be everywhere in the world. Now if we had an undo button, and we could go back and isolate it and grab it when it first started, if we could find it early and we had early detection and early response, and we could put each one of those viruses in jail, that's the only way to deal with something like a pandemic.

CA: Larry, that phrase you mentioned there, "early detection," "early response," that was a key theme of that talk, you made us all repeat it several times. Is that still the key to preventing a pandemic?

LB: Oh, surely. You know, when you have a pandemic, something moving at exponential speed, if you miss the first two weeks, if you're late the first two weeks, it's not the deaths and the illness from the first two weeks you lose, it's the two weeks at the peak. Those are prevented if you act early. Early response is critical, early detection is a condition precedent.

CA: And how would you grade the world on its early detection, early response to COVID-19?

LB: Of course, you gave me this question earlier, so I've been thinking a lot about it. I think I would go through the countries, and I've actually made a list. I think the island republics of Taiwan, Iceland and certainly New Zealand would get an A. The island republic of the UK and the United States -- which is not an island, no matter how much we may think we are -- would get a failing grade. I'd give a B to South Korea and to Germany. And in between ... So it's a very heterogeneous response, I think. The world as a whole is faltering. We shouldn't be proud of what's happening right now.

CA: I mean, we got the detection pretty early, or at least some doctors in China got the detection pretty early.

LB: Earlier than the 2002 SARS, which took six months. This took about six weeks. And detection means not only finding it, but knowing what it is. So I would give us a pretty good score on that. The transparency, the communication -- those are other issues.

CA: So what was the key mistake that you think the countries you gave an F to made?

LB: I think fear, political incompetence, interference, not taking it seriously soon enough -- it's pretty human. I think throughout history, pretty much every pandemic is first viewed with denial and doubt. But those countries that acted quickly, and even those who started slow, like South Korea, they could still make up for it, and they did really well. We've had two months that we've lost. We've given a virus that moves exponentially a two-month head start. That's not a good idea, Chris.

CA: No, indeed. I mean, there's so much puzzling information still out there about this virus. What do you think the scientific consensus is going to likely end up being on, like, the two key numbers of its infectiousness and its fatality rate?

LB: So I think the kind of equation to keep in mind is that the virus moves dependent on three major issues. One is the R0, the first number of secondary cases that there are when the virus emerges. In this case, people talk about it being 2.2, 2.4. But a really important paper three weeks ago, in the "Emerging Infectious Diseases" journal came out, suggesting that looking back on the Wuhan data, it's really 5.7. So for argument's sake, let's say that the virus is moving at exponential speed and the exponent is somewhere between 2.2 and 5.7. The other two factors that matter are the incubation period or the generation time. The longer that is, the slower the pandemic appears to us. When it's really short, like six days, it moves like lightning. And then the last, and the most important -- and it's often overlooked -- is the density of susceptibles. This is a novel virus, so we want to know how many customers could it potentially have. And as it's novel, that's eight billion of us. The world is facing a virus that looks at all of us like equally susceptible. Doesn't matter our color, our race, or how wealthy we are.

CA: I mean, none of the numbers that you've mentioned so far are in themselves different from any other infections in recent years. What is the combination that has made this so deadly?

LB: Well, it is exactly the combination of the short incubation period and the high transmissibility. But you know, everybody on this call has known somebody who has the disease. Sadly, many have lost a loved one. This is a terrible disease when it is serious. And I get calls from doctors in emergency rooms and treating people in ICUs all over the world, and they all say the same thing: "How do I choose who is going to live and who is going to die? I have so few tools to deal with." It's a terrifying disease, to die alone with a ventilator in your lungs, and it's a disease that affects all of our organs. It's a respiratory disease -- perhaps misleading. Makes you think of a flu. But so many of the patients have blood in their urine from kidney disease, they have gastroenteritis, they certainly have heart failure very often, we know that it affects taste and smell, the olfactory nerves, we know, of course, about the lung. The question I have: is there any organ that it does not affect? And in that sense, it reminds me all too much of smallpox.

CA: So we're in a mess. What's the way forward from here?

LB: Well, the way forward is still the same. Rapid detection, rapid response. Finding every case, and then figuring out all the contacts. We've got great new technology for contact tracing, we've got amazing scientists working at the speed of light to give us test kits and antivirals and vaccines. We need to slow down, the Buddhists say slow down time so that you can put your heart, your soul, into that space. We need to slow down the speed of this virus, which is why we do social distancing. Just to be clear -- flattening the curve, social distancing, it doesn't change the absolute number of cases, but it changes what could be a Mount Fuji-like peak into a pulse, and then we won't also lose people because of competition for hospital beds, people who have heart attacks, need chemotherapy, difficult births, can get into the hospital, and we can use the scarce resources we have, especially in the developing world, to treat people. So slow down, slow down the speed of the epidemic, and then in the troughs, in between waves, jump on, double down, step on it, and find every case, trace every contact, test every case, and then only quarantine the ones who need to be quarantined, and do that until we have a vaccine.

CA: So it sounds like we have to get past the stage of just mitigation, where we're just trying to take a general shutdown, to the point where we can start identifying individual cases again and contact-trace for them and treat them separately. I mean, to do that, that seems like it's going to take a step up of coordination, ambition, organization, investment, that we're not really seeing the signs of yet in some countries. Can we do this, how can we do this?

LB: Oh, of course we can do this. I mean, Taiwan did it so beautifully, Iceland did it so beautifully, Germany, all with different strategies, South Korea. It really requires competent governance, a sense of seriousness, and listening to the scientists, not the politicians following the virus. Of course we can do this. Let me remind everybody -- this is not the zombie apocalypse, it's not a mass extinction event. You know, 98, 99 percent of us are going to get out of this alive. We need to deal with it the way we know we can, and we need to be the best version of ourselves. Both sitting at home as well as in science, and certainly in leadership.

CA: And might there be even worse pathogens out there in the future? Like, can you picture or describe an even worse combination of those numbers that we should start to get ready for?

LB: Well, smallpox had an R0 of 3.5 to 4.5, so that's probably about what I think this COVID will be. But it killed a third of the people. But we had a vaccine. So those are the different sets that you have. But what I'm mostly worried about, and the reason that we made "Contagion" and that was a fictional virus -- I repeat, for those of you watching, that's fiction. We created a virus that killed a lot more than this one did.

CA: You're talking about the movie "Contagion" that's been trending on Netflix. And you were an advisor for.

LB: Absolutely, that's right. But we made that movie deliberately to show what a real pandemic looked like, but we did choose a pretty awful virus. And the reason we showed it like that, going from a bat to an apple, to a pig, to a cook, to Gwyneth Paltrow, was because that is in nature what we call spillover, as zoonotic diseases, diseases of animals, spill over to human beings. And if I look backwards three decades or forward three decades -- looking backward three decades, Ebola, SARS, Zika, swine flu, bird flu, West Nile, we can begin almost a catechism and listen to all the cacophony of these names. But there were 30 to 50 novel viruses that jumped into human beings. And I'm afraid, looking forward, we are in the age of pandemics, we have to behave like that, we need to practice One Health, we need to understand that we're living in the same world as animals, the environment, and us, and we get rid of this fiction that we are some kind of special species. To the virus, we're not.

CA: Mmm. You mentioned vaccines, though. Do you see any accelerated path to a vaccine?

LB: I do. I'm actually excited to see that we're doing something that we only get to think of in computer science, which is we're changing what should have always been, or has always been, rather, multiple sequential processes. Do safety testing, then you test for effectiveness, then for efficiency. And then you manufacture. We're doing all three or four of those steps, instead of doing it in sequence, we're doing in parallel. Bill Gates has said he's going to build seven vaccine production lines in the United States, and start preparing for production, not knowing what the end vaccine is going to be. We're simultaneously doing safety tests and efficacy tests. I think the NIH has jumped up. I'm very thrilled to see that.

CA: And how does that translate into a likely time line, do you think? A year, 18 months, is that possible?

LB: You know, Tony Fauci is our guru in this, and he said 12 to 18 months. I think that we will do faster than that in the initial vaccine. But you may have heard that this virus may not give us the long-term immunity -- that something like smallpox would do. So we're trying to make vaccines where we add adjuvants that actually make the vaccine create better immunity than the disease, so that we can confer immunity for many years. That's going to take a little longer.

CA: Last question, Larry. Back in 2006, as a winner of the TED Prize, we granted you a wish, and you wished the world would create this pandemic preparedness system that would prevent something like this happening. I feel like we, the world, let you down. If you were to make another wish now, what would it be?

LB: Well, I don't think we're let down in terms of speed of detection. I'm actually pretty pleased. When we met in 2006, the average one of these viruses leaping from an animal to a human, it took us six months to find that -- like the first Ebola, for example. We're now finding the first cases in two weeks. I'm not unhappy about that, I'd like to push it down to a single incubation period. It's a bigger issue for me. What I found is that in the Smallpox Eradication Programme people of all colors, all religions, all races, so many countries, came together. And it took working as a global community to conquer a global pandemic. Now, I feel that we have become victims of centrifugal forces. We're in our nationalistic kind of barricades. We will not be able to conquer a pandemic unless we believe we're all in it together. This is not some Age of Aquarius, or Kumbaya statement, this is what a pandemic forces us to realize. We are all in it together, we need a global solution to a global problem. Anything less than that is unthinkable.

CA: Larry Brilliant, thank you so very much.

LB: Thank you, Chris.