When you're working on a big problem like climate change, it's almost inevitable that there will be moments where you feel disappointed. What's more of a problem is when those occasional disappointments turn into a feeling of being stuck all of the time. When you go, "Oh my gosh, it doesn't matter, whatever I'm trying, it just doesn't seem to be making enough of a difference." How do we avoid getting stuck like that? Is there an antidote?

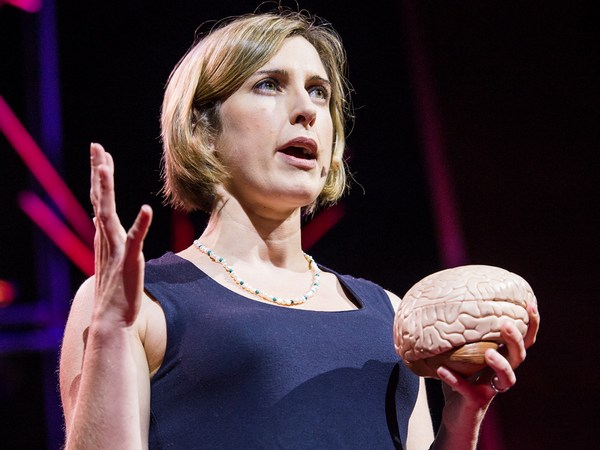

I'm a neuroscientist, and about 20 years ago, I became interested in the neuroscience of polarization. In the work I did, I learned something really unexpected about how people change. When you become deeply engaged with an issue, it's usually because you've taken some action first, without having any strong views at that particular moment. This can happen on personal decisions, like when you start to think about whether you're going to be changing jobs. It can also apply to questions like how you'll be voting in the next election, or what climate movement organization you're going to join.

For a while, you may be wrestling with the question "What's the right choice for me?" But then, at some point, your brain will make a first, tentative decision. It will say, "You know, based on all the thinking that I've done so far, I'm going to be doing this." Sending that job application, vote for this candidate, go to a meeting of this organization. You know, just to check out how they are.

Within a few seconds of making that decision, there's a burst of activity in your brain. It gives yourself a pat on the back for the decision that you just made. And then, through a process of self-justification and self-persuasion, you gradually make yourself more certain of the correctness and the importance of your actions. We call this process "actions drive beliefs." The things you do change the stuff that's inside your head.

Here's the good news. Actions drive beliefs is the key to stop feeling stuck. Here's why.

As a neuroscientist, I used to go mostly to neuroscience conferences, but from 2015, I was invited more and more to climate communication events. And I noticed something very strange in those events. The actions drive beliefs insight was completely missing from the conversations. Instead, I heard the same idea over and over again. "How do we raise awareness about climate change such that politicians, corporate leaders, citizens will take urgent action?" This idea is still so common that we call this the conventional wisdom, the popular view about climate action. Raise awareness first, then translate that into action.

So there is a lot less agreement, however, on how exactly to do this. And the arguments about this are so persistent that you can almost play bingo on a number of statements that are guaranteed to come up. So to help you spot those statements, I made a bingo card. The conventional wisdom climate comms bingo card.

(Laughter)

So someone will say we need to provide clear facts and information to people.

Others will say, "No, we need to do more than that. It's about educating people. It's about making them climate-literate."

“No, no facts don’t work,” someone else will say. “It’s all about emotional responses.”

And that then splits into: “We need to scare people into action.”

"No, we need to give them hope."

"Hold on, not so fast. We need to find the right balance of fear and hope."

"Yeah, but you know what? Above all, it's very important that we tell the truth about climate change." And bingo, back to facts and information.

(Laughter)

So, out of these -- facts, truth, fear or hope -- what works best?

None of them do. None of these flavors of the conventional wisdom are very good at driving action across society.

Let's start with fear. You've probably already heard someone say that you shouldn't be using fear. But others disagree. They will say, “You know the problem is that people aren’t scared enough yet. We need to scare them more. We need to terrify them, and then, they will do something about it. That's what worked for me," they will often say.

Now the science on this is pretty clear, though. For every person that is motivated by the scariness of climate change, there’s some other people who become hopeless and others who will switch off from the issue altogether. But what's really counterintuitive is that some people will also become climate deniers. "Why are these people trying to scare me like that?" they will say. "Isn't that a little bit suspicious?" And that question may kick off for them a self-persuasion process that takes them in the direction of full-blown denial.

What these different responses are telling us is that we can't rely on the fear factor of climate change to drive action across society. Instead, it creates the polarization and the messy divisions we see happening right now.

By the way, there is no right level of scariness. There is no right mixture of fear and hope that gets you out of this mess. Emotions are simply not predictable drivers of action. Thinking that you can pull some emotional strings and some action will pop out, that's really not how people work.

What if, instead of emotions, you think it's about explaining facts and telling the truth? Enter Ginger the dog. Ginger stands for all those situations in life where what you think you are saying to other people is not what they hear. We call this the Ginger dog effect because of a Far Side cartoon of a man berating his dog, in very long sentences, for doing something naughty, and all the dog hears is "Blah, blah, blah, Ginger, blah, blah blah."

(Laughter)

This Ginger effect is so common that we see this happening on words that we’re using all the time. But often, it goes undetected. Take climate risk. The word "risk" has such different meanings for climate scientists and economists that when they talk about climate risk, they're like ships sailing past each other in the night without any real understanding flowing between them.

And in those situations, it can also lead to frustration. Take climate action. To some people, they understand it as a personal action, and they then think of calls for more action as letting politicians and corporations off the hook. To other people, it means protest activism, but some people feel very positive about this, and other people feel very negative about this. And you're setting yourself up for a lot of frustration when you start to talk across those Ginger divides.

And that brings us to the next insight. "Ignorant, stupid, crazy, evil" thinking. Once self-persuasion has made you certain of something, you need to have an explanation for people who disagree with you. You actually have a lot of areas in your brain that become involved in this. Neuroscientists call this the social brain. Now the more you disagree with someone, the more your social brain will automatically fill in the reasons for that disagreement. "They're ignorant. They don't know the things that I know. They're too stupid or crazy to ever understand the things that I know." And the final one is where your social brain tells you, "You know, they do know the things that I know, but for their own hidden motives, they're saying something different. They're bad-faith actors. They're villains. They're evil people."

So how do we use all this knowledge about your brain to help you to get unstuck? A first useful step is to let go of judgment. When your social brain is whispering in your ear that someone who disagrees with you is stupid, crazy or evil, you don't have to believe that. Instead, ask yourself the question "What if they went through their own process of self-persuasion, just like me?" I know this may be difficult, but give it a try. It can really help you to get unstuck.

A second step is to manage Ginger better. When you feel frustration at someone responding with indifference or opposition, it’s likely that they understood some keywords differently from you. Try to surface that difference in understanding, and asking a question like, "What do you mean when you say X is a good way to start doing that?"

A third step is to let go of the idea that you need to persuade other people of the facts of climate change before you can start working with them. Instead of trying to persuade, create the conditions for self-persuasion, create opportunities for action and invite people into those.

Now paradoxically, you can also apply this to yourself. If you're stuck and you don't know how to overcome a barrier, try to identify a next concrete action that you can do. This can be an improving action, which is a small step in the direction of trying to solve a problem. But far more often, you'll actually need an exploratory action. This is when you realize that you're just making far too many assumptions about why those other people are opposing your views, and you need to find out more about their concerns.

To get the ball rolling on that, ask the question: “What keeps you awake at night?” And you will learn a lot about your next potential actions from the things that people tell you in that situation. And once you've activated your own process of doing, once you're in your own cycle of actions drive beliefs, tell your stories of doing, not as a tool to persuade other people that they should be doing the same, but simply because the story of how you overcame a barrier might inspire someone else to solve their own problem of feeling stuck.

We see that one person's action inspires action in someone else every single day. We see it in schools, in community energy projects, in journalists and newsrooms, in financial investors, in lawyers, and even in how countries are acting on climate change. It's early days, but if we keep on doing this, these actions will start to grow exponentially and will ripple through the whole of society. When we start seeing this, we will feel no longer stuck.

Thank you.

(Cheers and applause)