What do these animals have in common? More than you might think. Along with over 5,000 other species, they're mammals, or members of class mammalia. All mammals are vertebrates, meaning they have backbones. But mammals are distinguished from other vertebrates by a number of shared features. That includes warm blood, body hair or fur, the ability to breathe using lungs, and nourishing their young with milk. But despite these similarities, these creatures also have many biological differences, and one of the most remarkable is how they give birth. Let's start with the most familiar, placental mammals. This group includes humans, cats, dogs, giraffes, and even the blue whale, the biggest animal on Earth. Its placenta, a solid disk of blood-rich tissue, attaches to the wall of the uterus to support the developing embryo. The placenta is what keeps the calf alive during pregnancy. Directly connected to the mother's blood supply, it funnels nutrients and oxygen straight into the calf's body via the umbilical cord, and also exports its waste. Placental mammals can spend far longer inside the womb than other mammals. Baby blue whales, for instance, spend almost a full year inside their mother. The placenta keeps the calf alive right up until its birth, when the umbilical cord breaks and the newborn's own respiratory, circulatory, and waste disposal systems take over. Measuring about 23 feet, a newborn calf is already able to swim. It will spend the next six months drinking 225 liters of its mothers thick, fatty milk per day. Meanwhile, in Australia, you can find a second type of mammal - marsupials. Marsupial babies are so tiny and delicate when they're born that they must continue developing in the mother's pouch. Take the quoll, one of the world's smallest marsupials, which weighs only 18 milligrams at birth, the equivalent of about 30 sugar grains. The kangaroo, another marsupial, gives birth to a single jelly bean-sized baby at a time. The baby crawls down the middle of the mother's three vaginas, then must climb up to the pouch, where she spends the next 6-11 months suckling. Even after the baby kangaroo leaves this warm haven, she'll return to suckle milk. Sometimes, she's just one of three babies her mother is caring for. A female kangaroo can often simultaneously support one inside her uterus and another in her pouch. In unfavorable conditions, female kangaroos can pause their pregnancies. When that happens, she's able to produce two different kinds of milk, one for her newborn, and one for her older joey. The word mammalia means of the breast, which is a bit of a misnomer because while kangaroos do produce milk from nipples in their pouches, they don't actually have breasts. Nor do monotremes, the third and arguably strangest example of mammalian birth. There were once hundreds of monotreme species, but there are only five left: four species of echidnas and the duck-billed platypus. The name monotreme means one hole referring to the single orifice they use for reproduction, excretion, and egg-laying. Like birds, reptiles, fish, dinosaurs, and others, these species lay eggs instead of giving birth to live young. Their eggs are soft-shelled, and when their babies hatch, they suckle milk from pores on their mother's body until they're large enough to feed themselves. Despite laying eggs and other adaptations that we associate more with non-mammals, like the duck-bill platypus's webbed feet, bill, and the venomous spur males have on their feet, they are, in fact, mammals. That's because they share the defining characteristics of mammalia and are evolutionarily linked to the rest of the class. Whether placental, marsupial, or monotreme, each of these creatures and its unique birthing methods, however bizarre, have succeeded for many millennia in bringing new life and diversity into the mammal kingdom.

Related talks

Nassim Assefi and Brian A. Levine: How in vitro fertilization (IVF) works

Alex Gendler: Myths and misconceptions about evolution

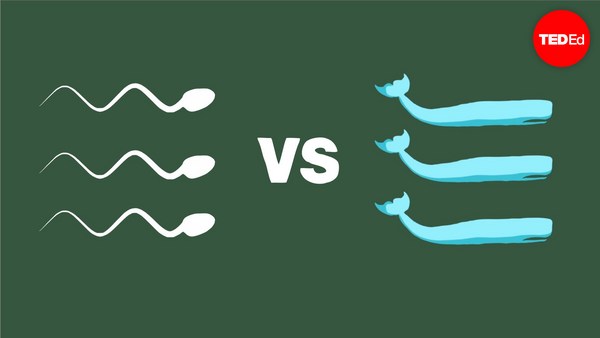

Aatish Bhatia: The physics of human sperm vs. the physics of the sperm whale

Katie Hinde: What we don't know about mother's milk

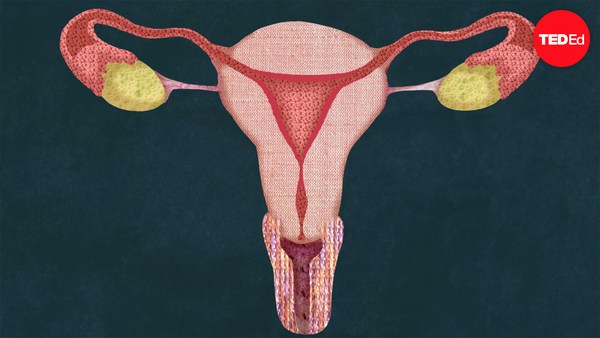

TED-Ed: Why do women have periods?