There was a day, about 10 years ago, when I asked a friend to hold a baby dinosaur robot upside down. It was this toy called a Pleo that I had ordered, and I was really excited about it because I've always loved robots. And this one has really cool technical features. It had motors and touch sensors and it had an infrared camera. And one of the things it had was a tilt sensor, so it knew what direction it was facing. And when you held it upside down, it would start to cry. And I thought this was super cool, so I was showing it off to my friend, and I said, "Oh, hold it up by the tail. See what it does." So we're watching the theatrics of this robot struggle and cry out. And after a few seconds, it starts to bother me a little, and I said, "OK, that's enough now. Let's put him back down." And then I pet the robot to make it stop crying.

And that was kind of a weird experience for me. For one thing, I wasn't the most maternal person at the time. Although since then I've become a mother, nine months ago, and I've learned that babies also squirm when you hold them upside down.

(Laughter)

But my response to this robot was also interesting because I knew exactly how this machine worked, and yet I still felt compelled to be kind to it. And that observation sparked a curiosity that I've spent the past decade pursuing. Why did I comfort this robot? And one of the things I discovered was that my treatment of this machine was more than just an awkward moment in my living room, that in a world where we're increasingly integrating robots into our lives, an instinct like that might actually have consequences, because the first thing that I discovered is that it's not just me.

In 2007, the Washington Post reported that the United States military was testing this robot that defused land mines. And the way it worked was it was shaped like a stick insect and it would walk around a minefield on its legs, and every time it stepped on a mine, one of the legs would blow up, and it would continue on the other legs to blow up more mines. And the colonel who was in charge of this testing exercise ends up calling it off, because, he says, it's too inhumane to watch this damaged robot drag itself along the minefield. Now, what would cause a hardened military officer and someone like myself to have this response to robots?

Well, of course, we're primed by science fiction and pop culture to really want to personify these things, but it goes a little bit deeper than that. It turns out that we're biologically hardwired to project intent and life onto any movement in our physical space that seems autonomous to us. So people will treat all sorts of robots like they're alive. These bomb-disposal units get names. They get medals of honor. They've had funerals for them with gun salutes. And research shows that we do this even with very simple household robots, like the Roomba vacuum cleaner.

(Laughter)

It's just a disc that roams around your floor to clean it, but just the fact it's moving around on its own will cause people to name the Roomba and feel bad for the Roomba when it gets stuck under the couch.

(Laughter)

And we can design robots specifically to evoke this response, using eyes and faces or movements that people automatically, subconsciously associate with states of mind. And there's an entire body of research called human-robot interaction that really shows how well this works. So for example, researchers at Stanford University found out that it makes people really uncomfortable when you ask them to touch a robot's private parts.

(Laughter)

So from this, but from many other studies, we know, we know that people respond to the cues given to them by these lifelike machines, even if they know that they're not real.

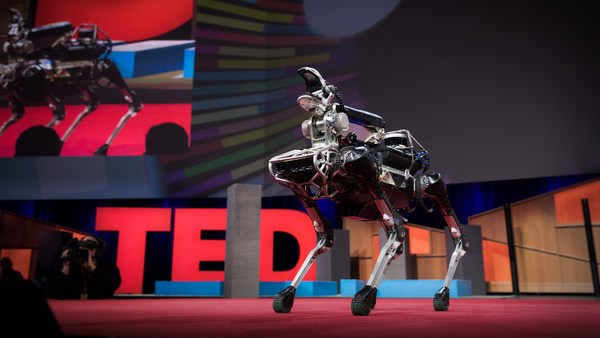

Now, we're headed towards a world where robots are everywhere. Robotic technology is moving out from behind factory walls. It's entering workplaces, households. And as these machines that can sense and make autonomous decisions and learn enter into these shared spaces, I think that maybe the best analogy we have for this is our relationship with animals. Thousands of years ago, we started to domesticate animals, and we trained them for work and weaponry and companionship. And throughout history, we've treated some animals like tools or like products, and other animals, we've treated with kindness and we've given a place in society as our companions. I think it's plausible we might start to integrate robots in similar ways.

And sure, animals are alive. Robots are not. And I can tell you, from working with roboticists, that we're pretty far away from developing robots that can feel anything. But we feel for them, and that matters, because if we're trying to integrate robots into these shared spaces, we need to understand that people will treat them differently than other devices, and that in some cases, for example, the case of a soldier who becomes emotionally attached to the robot that they work with, that can be anything from inefficient to dangerous. But in other cases, it can actually be useful to foster this emotional connection to robots. We're already seeing some great use cases, for example, robots working with autistic children to engage them in ways that we haven't seen previously, or robots working with teachers to engage kids in learning with new results. And it's not just for kids. Early studies show that robots can help doctors and patients in health care settings.

This is the PARO baby seal robot. It's used in nursing homes and with dementia patients. It's been around for a while. And I remember, years ago, being at a party and telling someone about this robot, and her response was, "Oh my gosh. That's horrible. I can't believe we're giving people robots instead of human care." And this is a really common response, and I think it's absolutely correct, because that would be terrible. But in this case, it's not what this robot replaces. What this robot replaces is animal therapy in contexts where we can't use real animals but we can use robots, because people will consistently treat them more like an animal than a device.

Acknowledging this emotional connection to robots can also help us anticipate challenges as these devices move into more intimate areas of people's lives. For example, is it OK if your child's teddy bear robot records private conversations? Is it OK if your sex robot has compelling in-app purchases?

(Laughter)

Because robots plus capitalism equals questions around consumer protection and privacy.

And those aren't the only reasons that our behavior around these machines could matter. A few years after that first initial experience I had with this baby dinosaur robot, I did a workshop with my friend Hannes Gassert. And we took five of these baby dinosaur robots and we gave them to five teams of people. And we had them name them and play with them and interact with them for about an hour. And then we unveiled a hammer and a hatchet and we told them to torture and kill the robots.

(Laughter)

And this turned out to be a little more dramatic than we expected it to be, because none of the participants would even so much as strike these baby dinosaur robots, so we had to improvise a little, and at some point, we said, "OK, you can save your team's robot if you destroy another team's robot."

(Laughter)

And even that didn't work. They couldn't do it. So finally, we said, "We're going to destroy all of the robots unless someone takes a hatchet to one of them." And this guy stood up, and he took the hatchet, and the whole room winced as he brought the hatchet down on the robot's neck, and there was this half-joking, half-serious moment of silence in the room for this fallen robot.

(Laughter)

So that was a really interesting experience. Now, it wasn't a controlled study, obviously, but it did lead to some later research that I did at MIT with Palash Nandy and Cynthia Breazeal, where we had people come into the lab and smash these HEXBUGs that move around in a really lifelike way, like insects. So instead of choosing something cute that people are drawn to, we chose something more basic, and what we found was that high-empathy people would hesitate more to hit the HEXBUGS.

Now this is just a little study, but it's part of a larger body of research that is starting to indicate that there may be a connection between people's tendencies for empathy and their behavior around robots. But my question for the coming era of human-robot interaction is not: "Do we empathize with robots?" It's: "Can robots change people's empathy?" Is there reason to, for example, prevent your child from kicking a robotic dog, not just out of respect for property, but because the child might be more likely to kick a real dog?

And again, it's not just kids. This is the violent video games question, but it's on a completely new level because of this visceral physicality that we respond more intensely to than to images on a screen. When we behave violently towards robots, specifically robots that are designed to mimic life, is that a healthy outlet for violent behavior or is that training our cruelty muscles? We don't know ... But the answer to this question has the potential to impact human behavior, it has the potential to impact social norms, it has the potential to inspire rules around what we can and can't do with certain robots, similar to our animal cruelty laws. Because even if robots can't feel, our behavior towards them might matter for us. And regardless of whether we end up changing our rules, robots might be able to help us come to a new understanding of ourselves.

Most of what I've learned over the past 10 years has not been about technology at all. It's been about human psychology and empathy and how we relate to others. Because when a child is kind to a Roomba, when a soldier tries to save a robot on the battlefield, or when a group of people refuses to harm a robotic baby dinosaur, those robots aren't just motors and gears and algorithms. They're reflections of our own humanity.

Thank you.

(Applause)