I'm a very lucky person. I've been privileged to see so much of our beautiful Earth and the people and creatures that live on it. And my passion was inspired at the age of seven, when my parents first took me to Morocco, at the edge of the Sahara Desert. Now imagine a little Brit somewhere that wasn't cold and damp like home. What an amazing experience. And it made me want to explore more.

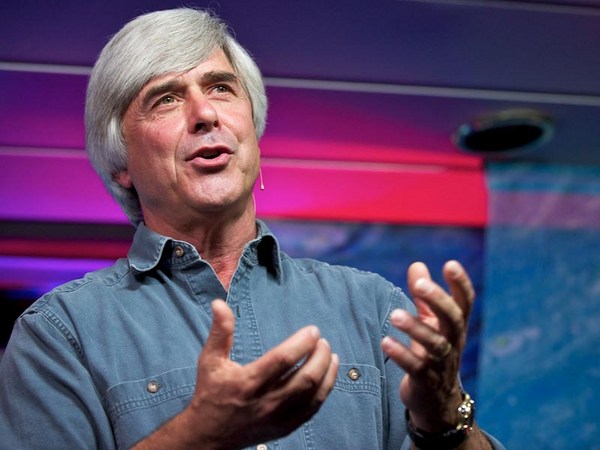

So as a filmmaker, I've been from one end of the Earth to the other trying to get the perfect shot and to capture animal behavior never seen before. And what's more, I'm really lucky, because I get to share that with millions of people worldwide. Now the idea of having new perspectives of our planet and actually being able to get that message out gets me out of bed every day with a spring in my step.

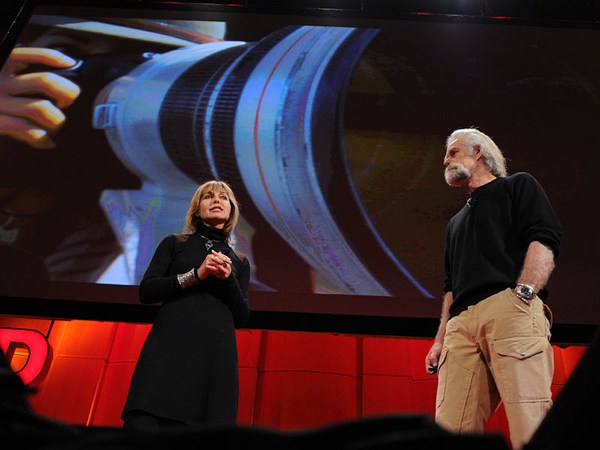

You might think that it's quite hard to find new stories and new subjects, but new technology is changing the way we can film. It's enabling us to get fresh, new images and tell brand new stories. In Nature's Great Events, a series for the BBC that I did with David Attenborough, we wanted to do just that.

Images of grizzly bears are pretty familiar. You see them all the time, you think. But there's a whole side to their lives that we hardly ever see and had never been filmed. So what we did, we went to Alaska, which is where the grizzlies rely on really high, almost inaccessible, mountain slopes for their denning. And the only way to film that is a shoot from the air.

(Video) David Attenborough: Throughout Alaska and British Columbia, thousands of bear families are emerging from their winter sleep. There is nothing to eat up here, but the conditions were ideal for hibernation. Lots of snow in which to dig a den. To find food, mothers must lead their cubs down to the coast, where the snow will already be melting. But getting down can be a challenge for small cubs. These mountains are dangerous places, but ultimately the fate of these bear families, and indeed that of all bears around the North Pacific, depends on the salmon.

KB: I love that shot. I always get goosebumps every time I see it. That was filmed from a helicopter using a gyro-stabilized camera. And it's a wonderful bit of gear, because it's like having a flying tripod, crane and dolly all rolled into one. But technology alone isn't enough. To really get the money shots, it's down to being in the right place at the right time. And that sequence was especially difficult.

The first year we got nothing. We had to go back the following year, all the way back to the remote parts of Alaska. And we hung around with a helicopter for two whole weeks. And eventually we got lucky. The cloud lifted, the wind was still, and even the bear showed up. And we managed to get that magic moment.

For a filmmaker, new technology is an amazing tool, but the other thing that really, really excites me is when new species are discovered. Now, when I heard about one animal, I knew we had to get it for my next series, Untamed Americas, for National Geographic. In 2005, a new species of bat was discovered in the cloud forests of Ecuador. And what was amazing about that discovery is that it also solved the mystery of what pollinated a unique flower. It depends solely on the bat.

Now, the series hasn't even aired yet, so you're the very first to see this. See what you think. (Video) Narrator: The tube-lipped nectar bat. A pool of delicious nectar lies at the bottom of each flower's long flute. But how to reach it? Necessity is the mother of evolution. (Music) This two-and-a-half-inch bat has a three-and-a-half-inch tongue, the longest relative to body length of any mammal in the world. If human, he'd have a nine-foot tongue. (Applause) KB: What a tongue. We filmed it by cutting a tiny little hole in the base of the flower and using a camera that could slow the action by 40 times. So imagine how quick that thing is in real life.

Now people often ask me, "Where's your favorite place on the planet?" And the truth is I just don't have one. There are so many wonderful places. But some locations draw you back time and time again. And one remote location -- I first went there as a backpacker; I've been back several times for filming, most recently for Untamed Americas -- it's the Altiplano in the high Andes of South America, and it's the most otherworldly place I know. But at 15,000 feet, it's tough. It's freezing cold, and that thin air really gets you. Sometimes it's hard to breathe, especially carrying all the heavy filming equipment. And that pounding head just feels like a constant hangover. But the advantage of that wonderful thin atmosphere is that it enables you to see the stars in the heavens with amazing clarity. Have a look.

(Video) Narrator: Some 1,500 miles south of the tropics, between Chile and Bolivia, the Andes completely change. It's called the Altiplano, or "high plains" -- a place of extremes and extreme contrasts. Where deserts freeze and waters boil. More like Mars than Earth, it seems just as hostile to life. The stars themselves -- at 12,000 feet, the dry, thin air makes for perfect stargazing. Some of the world's astronomers have telescopes nearby. But just looking up with the naked eye, you really don't need one. (Music) (Applause)

KB: Thank you so much for letting me share some images of our magnificent, wonderful Earth. Thank you for letting me share that with you. (Applause)