In a 1973 study, 20 volunteers got drunk once a week for 8 consecutive weeks, each time on a different alcoholic beverage, and each time with precisely the same dosage— this was science, after all.

The goal of this experiment was to find out which alcoholic drinks cause worse hangovers. Of course, it takes much more than one small study to answer such a question. Since then, science has learned a lot about hangovers— though some mysteries remain.

The molecule responsible for hangovers is ethanol, which we colloquially refer to as alcohol. Ethanol is present in all alcoholic beverages, and generally speaking, the more ethanol, the greater the potential for a hangover. The symptoms and severity can vary depending on weight, age, genetics, and other factors. But still, hangovers generally share some common— and unpleasant— features. So how exactly does alcohol cause a hangover? And is there any way to reliably prevent one?

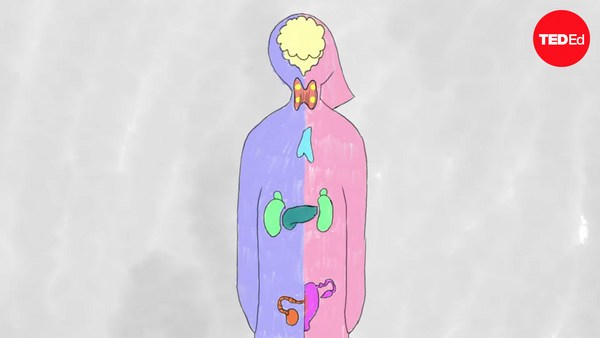

Alcohol slows down the communication between neural cells. After someone has had their last drink, as the concentration of alcohol in the blood drops back to zero, the brain rebounds from sedation and swings in the other direction, entering a hyperactive state. This may lead to the tremors or rapid heartbeat associated with hangovers. It also makes sleep shorter and less restful than normal. But these effects are just the beginning— alcohol impacts so many of the body’s processes, throwing delicate balances off-kilter. And even the most familiar hangover symptoms have surprising contributors.

For example, alcohol disrupts levels of many hormones. One of those hormones is cortisol. Normally, fluctuating cortisol levels help regulate wakefulness throughout the day and night. So the disruption in cortisol during a hangover may cause people to feel groggy or disoriented. Another hormone alcohol interferes with is vasopressin, which normally decreases the volume of urine made by the kidneys. By decreasing levels of vasopressin, alcohol causes people to pee more and become dehydrated. Dehydration can lead to thirst, dry mouth, weakness, lightheadedness, and headache, one of the most common hangover symptoms. In addition to dehydration, hangover headaches can result from alcohol’s influence on chemical signaling in the brain, especially on neurotransmitters involved in pain signaling.

Alcohol can also damage mitochondria, which are responsible for producing the ATP that gives us energy. This may contribute to the fatigue, weakness, and mood disturbances experienced during a hangover. Meanwhile, alcohol stimulates the immune system, leading to inflammation that can damage cells within the brain, affect mood, and impair memory. And it can irritate the gastrointestinal tract and inflame the lining of the stomach and intestines. Alcohol may also slow down stomach emptying, which could lead to increased production of gastric acid. This is why alcohol can cause stomach pain, nausea, and vomiting.

Alcoholic drinks also contain other substances that are produced during the fermentation process that give the drink its specific flavor. Some evidence suggests that one of these, methanol, is particularly bad for hangovers. The body doesn’t start metabolizing methanol until it’s done processing ethanol. And when it does, the toxic metabolites of methanol may potentially worsen the hangover symptoms. Beverages that are closer to pure ethanol, such as gin and vodka, may cause fewer hangover effects. Meanwhile, the presence of flavoring ingredients in beverages like whiskey, brandy, and red wine, may make these kinds of alcohol cause more hangover symptoms. So, the choice of alcoholic beverage matters, but any of them can cause hangovers, simply because they all contain alcohol.

So, do common hangover remedies actually work? Drinking water and electrolyte beverages can help reduce symptoms related to dehydration. And eating— especially carbs— can help replenish the glucose levels alcohol reduces. But ultimately, the only sure way to prevent a hangover is to drink alcohol in moderation or not at all.