I'm kind of tired of talking about simplicity, actually, so I thought I'd make my life more complex, as a serious play. So, I'm going to, like, go through some slides from way back when, and walk through them to give you a sense of how I end up here.

So, basically it all began with this whole idea of a computer. Who has a computer? Yeah. O.K., so, everyone has a computer. Even a mobile phone, it's a computer. And -- anyone remember this workbook, "Instant Activities for Your Apple" -- free poster in each book? This was how computing began. Don't forget: a computer came out; it had no software. You'd buy that thing, you'd bring it home, you'd plug it in, and it would do absolutely nothing at all. So, you had to program it, and there were great programming, like, tutorials, like this. I mean, this was great. It's, like, you know, Herbie the Apple II. It's such a great way to -- I mean, they should make Java books like this, and we've have no problem learning a program. But this was a great, grand time of the computer, when it was just a raw, raw, what is it? kind of an era. And, you see, this era coincided with my own childhood.

I grew up in a tofu factory in Seattle. Who of you grew up in a family business, suffered the torture? Yes, yes. The torture was good. Wasn't it good torture? It was just life-changing, you know. And so, in my life, you know, I was in the tofu; it was a family business. And my mother was a kind of a designer, also. She'd make this kind of, like, wall of tofu cooking, and it would confuse the customers, because they all thought it was a restaurant. A bad sort of branding thing, or whatever. But, anyway, that's where I grew up, in this little tofu factory in Seattle, and it was kind of like this: a small room where I kind of grew up. I'm big there in that picture.

That's my dad. My dad was kind of like MacGyver, really: he would invent, like, ways to make things heavy. Like back here, there's like, concrete block technology here, and he would need the concrete blocks to press the tofu, because tofu is actually kind of a liquidy type of thing, and so you have to have heavy stuff to push out the liquid and make it hard. Tofu comes out in these big batches, and my father would sort of cut them by hand. I can't tell you -- family business story: you'd understand this -- my father was the most sincere man possible. He walked into a Safeway once on a rainy day, slipped, broke his arm, rushed out: he didn't want to inconvenience Safeway. So, instead, you know, my father's, like, arm's broken for two weeks in the store, and that week -- now, those two weeks were when my older brother and I had to do everything. And that was torture, real torture. Because, you see, we'd seen my father taking the big block of tofu and cutting it, like, knife in, zap, zap, zap. We thought, wow. So, the first time I did that, I went, like, whoa! Like this. Bad blocks. But anyways, the tofu to me was kind of my origin, basically. And because working in a store was so hard, I liked going to school; it was like heaven. And I was really good at school.

So, when I got to MIT, you know, as most of you who are creatives, your parents all told you not to be creative, right? So, same way, you know, I was good at art and good at math, and my father says, he's -- John's good at math. I went to MIT, did my math, but I had this wonderful opportunity, because computers had just become visual. The Apple -- Macintosh just came out; I had a Mac in hand when I went to MIT. And it was a time when a guy who, kind of, could cross the two sides -- it was a good time.

And so, I remember that my first major piece of software was on a direct copy of then-Aldus PageMaker. I made a desktop publishing system way back when, and that was, kind of, my first step into figuring out how to -- oh, these two sides are kind of fun to mix. And the problem when you're younger -- for all you students out there -- is, your head gets kind of big really easy. And when I was making icons, I was, like, the icon master, and I was, like, yeah, I'm really good at this, you know. And then luckily, you know, I had the fortune of going to something called a library, and in the library I came upon this very book. I found this book. It's called, "Thoughts on Design," by a man named Paul Rand. It's a little slim volume; I'm not sure if you've seen this. It's a very nice little book. It's about this guy, Paul Rand, who was one of the greatest graphic designers, and also a great writer as well. And when I saw this man's work, I realized how bad I was at design, or whatever I called it back then, and I suddenly had a kind of career goal, kind of in hot pursuit.

So I kind of switched. I went to MIT, finished. I got my masters, and then went to art school after that. And just began to design stuff, like chopstick wrappers, napkins, menus -- whatever I could get a handle on: sort of wheel-and-deal, move up in the design world, whatever. And isn't it that strange moment when you publish your design? Remember that moment -- publishing your designs? Remember that moment? It felt so good, didn't it? So, I was published, you know, so, wow, my design's in a book, you know? After that, things kind of got strange, and I got thinking about the computer, because the computer to me always, kind of, bothered me. I didn't quite get it. And Paul Rand was a kind of crusty designer, you know, a crusty designer, like a good -- kind of like a good French bread? You know, he wrote in one of his books: "A Yale student once said, 'I came here to learn how to design, not how to use a computer.' Design schools take heed." This is in the '80s, in the great clash of computer/non-computer people. A very difficult time, actually. And this to me was an important message from Rand.

And so I began to sort of mess with the computer at the time. This is the first sort of play thing I did, my own serious play. I built a working version of an Adobe Illustrator-ish thing. It looks like Illustrator; it can, like, draw. It was very hard to make this, actually. It took a month to make this part. And then I thought, what if I added this feature, where I can say, this point, you can fly like a bird. You're free, kind of thing. So I could, sort of, change the kind of stability with a little control there on the dial, and I can sort of watch it flip around. And this is in 1993. And when my professors saw this, they were very upset at me. They were saying, Why's it moving? They were saying, Make it stop now. Now, I was saying, Well, that's the whole point: it's moving. And he says, Well, when's it going to stop? And I said, Never. And he said, Even worse. Stop it now. I started studying this whole idea, of like, what is this computer? It's a strange medium. It's not like print. It's not like video. It lasts forever. It's a very strange medium. So, I went off with this, and began to look for things even more.

And so in Japan, I began to experiment with people. This is actually bad: human experiments. I would do these things where I'd have students become pens: there's blue pen, red pen, green pen, black pen. And someone sits down and draws a picture. They're laughing because he said, draw from the middle-right to the middle, and he kind of messed up. See, humans don't know how to take orders; the computer's so good at it. This guy figured out how to get the computer to draw with two pens at once: you know, you, pen, do this, and you, pen, do this. And so began to have multiple pens on the page -- again, hard to do with our hands. And then someone discovered this "a-ha moment" where you could use coordinate systems. We thought, ah, this is when it's going to happen. In the end, he drew a house. It was the most boring thing. It became computerish; we began to think computerish -- the X, Y system -- and so that was kind of a revelation.

And after this I wanted to build a computer out of people, called a human-powered computer. So, this happened in 1993. Sound down, please. It's a computer where the people are the parts. I have behind this wall a disk drive, a CPU, a graphics card, a memory system. They're picking up a giant floppy disk made of cardboard. It's put inside the computer. And that little program's on that cardboard disk. So, she wears the disk, and reads the data off the sectors of the disk, and the computer starts up; it sort of boots up, really. And it's a sort of a working computer. And when I built this computer, I had a moment of -- what is it called? -- the epiphany where I realized that the computer's just so fast. This computer appears to be fast - she's working pretty hard, and people are running around, and we think, wow, this is happening at a fast rate. And this computer's programmed to do only one thing, which is, if you move your mouse, the mouse changes on the screen. On the computer, when you move your mouse, that arrow moves around. On this computer, if you move the mouse, it takes half an hour for the mouse cursor to change. To give you a sense of the speed, the scale: the computer is just so amazingly fast, O.K.?

And so, after this I began to do experiments for different companies. This is something I did for Sony in 1996. It was three Sony "H" devices that responded to sound. So, if you talk into the mike, you'll hear some music in your headphones; if you talk in the phone, then video would happen. So, I began to experiment with industry in different ways with this kind of mixture of skills. I did this ad. I don't believe in this kind of alcohol, but I do drink sometimes. And Chanel. So, getting to do different projects.

And also, one thing I realized is that I like to make things. We like to make things. It's fun to make things. And so I never developed the ability to have a staff. I have no staff; it's all kind of made by hand -- these sort of broken hands. And these hands were influenced by this man, Mr. Inami Naomi. This guy was my kind of like mentor. He was the first digital media producer in Tokyo. He's the guy that kind of discovered me, and kind of got me going in digital media. He was such an inspirational guy. I remember, like, we'd be in his studio, like, at 2 a.m., and then he'd show up from some client meeting. He'd come in and say, you know, If I am here, everything is okay. And you'd feel so much better, you know. And I'll never forget how, like, but -- I'll never forget how, like, he had a sudden situation with his -- he had an aneurysm. He went into a coma. And so, for three years he was out, and he could only blink, and so I realized at this moment, I thought, wow -- how fragile is this thing we're wearing, this body and mind we're wearing, and so I thought, How do you go for it more? How do you take that time you have left and go after it? So, Naomi was pivotal in that.

And so, I began to think more carefully about the computer. This was a moment where I was thinking about, so, you have a computer program, it responds to motion -- X and Y -- and I realized that each computer program has all these images inside the program. So, if you can see here, you know, that program you're seeing in the corner, if you spread it out, it's all these things all at once. It's real simultaneity. It's nothing we're used to working with. We're so used to working in one vector. This is all at the same time. The computer lives in so many dimensions. And also, at the same time I was frustrated, because I would go to all these art and design schools everywhere, and there were these, like, "the computer lab," you know, and this is, like, in the late 1990s, and this is in Basel, a great graphic design school. And here's this, like, dirty, kind of, shoddy, kind of, dark computer room. And I began to wonder, Is this the goal? Is this what we want, you know?

And also, I began to be fascinated by machines -- you know, like copy machines -- and so this is actually in Basel. I noticed how we spent so much time on making it interactive -- this is, like, a touch screen -- and I noticed how you can only touch five places, and so, "why are we wasting so much interactivity everywhere?" became a question. And also, the sound: I discovered I can make my ThinkPad pretend it's a telephone. You get it? No? O.K. And also, I discovered in Logan airport, this was, like, calling out to me. Do you hear that? It's like cows. This is at 4 a.m. at Logan.

So, I was wondering, like, what is this thing in front of me, this computer thing? It didn't make any sense. So, I began to make things again. This is another series of objects made of old computers from my basement. I made -- I took my old Macintoshes and made different objects out of them from Tokyo. I began to be very disinterested in computers themselves, so I began to make paintings out of PalmPilots. I made this series of works. They're paintings I made and put a PalmPilot in the middle as a kind of display that's sort of thinking, I'm abstract art. What am I? I'm abstract. And so it keeps thinking out loud of its own abstraction.

I began to be fascinated by plastic, so I spent four months making eight plastic blocks perfectly optically transparent, as a kind of release of stress. Because of that, I became interested in blue tape, so in San Francisco, at C.C., I had a whole exhibition on blue tape. I made a whole installation out of blue tape -- blue painters' tape. And at this point my wife kind of got worried about me, so I stopped doing blue tape and began to think, Well, what else is there in life? And so computers, as you know, these big computers, there are now tiny computers. They're littler computers, so the one-chip computers, I began to program one-chip computers and make objects out of P.C. boards, LEDs. I began to make LED sculptures that would live inside little boxes out of MDF. This is a series of light boxes I made for a show in Italy. Very simple boxes: you just press one button and some LED interaction occurs. This is a series of lamps I made. This is a Bento box lamp: it's sort of a plastic rice lamp; it's very friendly. I did a show in London last year made out of iPods -- I used iPods as a material. So I took 16 iPod Nanos and made a kind of a Nano fish, basically. Recently, this is for Reebok. I've done shoes for Reebok as well, as a kind of a hobby for apparel.

So anyways, there are all these things you can do, but the thing I love the most is to experience, taste the world. The world is just so tasty. We think we'll go to a museum; that's where all the tastes are. No, they're all out there. So, this is, like, in front of the Eiffel Tower, really, actually, around the Louvre area. This I found, where nature had made a picture for me. This is a perfect 90-degree angle by nature. In this strange moment where, like, these things kind of appeared. We all are creative people. We have this gene defect in our mind. We can't help but stop, right? This feeling's a wonderful thing. It's the forever-always-on museum. This is from the Cape last year. I discovered that I had to find the equation of art and design, which we know as circle-triangle-square. It's everywhere on the beach, I discovered. I began to collect every instance of circle-triangle-square. I put these all back, by the way. And I also discovered how . some rocks are twins separated at birth. This is also out there, you know. I'm, like, how did this happen, kind of thing? I brought you guys together again.

So, three years ago I discovered, the letters M-I-T occurring in simplicity and complexity. My alma mater, MIT, and I had this moment -- a kind of M. Night Shayamalan moment -- where I thought, Whoa! I have to do this. And I went after it with passion. However, recently this RISD opportunity kind of arose -- going to RISD -- and I couldn't reconcile this real easy, because the letters had told me, MIT forever. But I discovered in the French word raison d'être. I was, like, aha, wait a second. And there RISD appeared. And so I realized it was O.K. to go.

So, I'm going to RISD, actually. Who's a RISD alum out there? RISD alums? Yeah, RISD. There we go, RISD. Woo, RISD. I'm sorry, I'm sorry, Art Center -- Art Center is good, too. RISD is kind of my new kind of passion, and I'll tell you a little bit about that. So, RISD is -- I was outside RISD, and some student wrote this on some block, and I thought, Wow, RISD wants to know what itself is. And I have no idea what RISD should be, actually, or what it wants to be, but one thing I have to tell you is that although I'm a technologist, I don't like technology very much. It's a, kind of, the qi thing, or whatever. People say, Are you going to bring RISD into the future? And I say, well, I'm going to bring the future back to RISD.

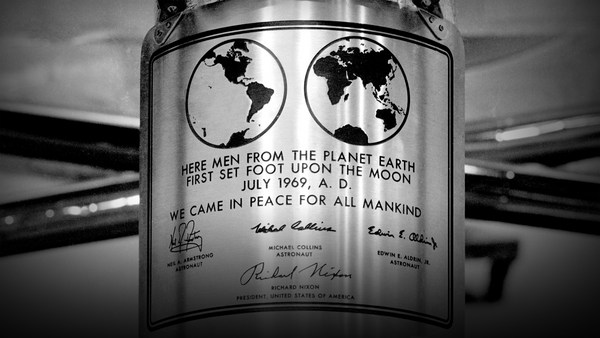

There's my perspective. Because in reality, the problem isn't how to make the world more technological. It's about how to make it more humane again. And if anything, I think RISD has a strange DNA. It's a strange exuberance about materials, about the world: a fascination that I think the world needs quite very much right now. So, thank you everyone.