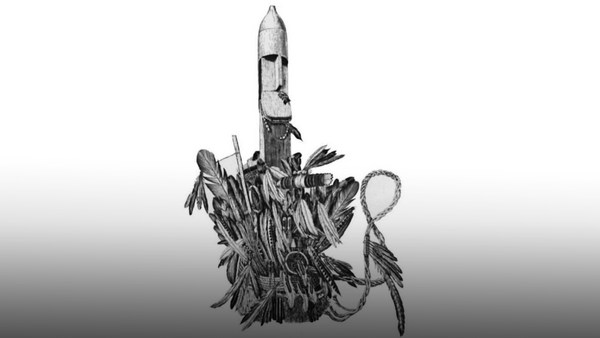

If you live in New York or London or some other so-called cultural capital, it’s likely that you visited an art museum that features a collection of African art. These collections usually consist of masks and sculptures, but also include weapons and ceremonial dress, cutlery, jewelry, and even toys. These objects are markers of traditions and cultural beliefs, but also of adaptation and ingenuity, science and spirituality. Cultural objects are the way that human beings say, “We were here.”

Have you ever wondered how these African objects ended up in museums? Some were bought by traders and tourists, some gifts exchanged in acts of friendship and some were excavated in archaeological digs. But then there are many others that were looted during raids, confiscated by colonial forces and stolen at gunpoint.

I’m an artist and I tell stories for a living. To tell stories you need imagination and memory. And in Kenya, we have a gap in our memory. So much of what happened in between the late 1800s until our independence in 1963 is missing because too many of the objects that tell the stories from that period are gone. According to a 2018 report on African cultural heritage, 90 percent of sub-Saharan Africa’s material cultural legacy is housed outside the African continent.

What does it mean for a society to lose so many objects? It means that we forget our religions and our spiritual practices. It means that we forget the names of our kingdoms and heroes. It means that we forget our music, our crafts and our languages. We forget our stories. And as a result, we adopt other people’s religions and call our own religions witchcraft. We start to eat burgers and pasta and look down on our indigenous foods and our children begin to believe in their hearts that other societies have richer cultures.

Where do you begin to fix something like this? One place to start is to find out exactly which objects are missing and where they are.

In 2018, as a member of The Nest Collective and together the coalition of Kenyan and European museums, artists and researchers, we co-founded the International Inventories Programme, which began creating a database of Kenyan cultural objects that are held outside our country. We called and e-mailed museums across North America and Europe, asking them if they had any Kenyan cultural objects in their collections. We hosted public debates about object restitution and created exhibitions to bring the debate into the public sphere. And that was the easy part. The more difficult part for us Kenyans was having to read through the most troubling historical texts and records from a time in history when Africans were on the receiving end of colonial force, violence and discrimination. Those texts are still difficult to read even today.

In two years, we collected data on more than 32,000 objects held by these institutions, and that might seem like a huge number, but there are many other institutions that haven’t yet replied to our requests. And that’s just Kenya. They are 46 other countries in sub-Saharan Africa that have experienced a similar extraction of objects.

Our next step is to publish this database online, so the data is accessible to community leaders who have been campaigning for the return of sacred objects, but also for every teacher, researcher and citizen who wants to find out what we are missing and where it can be found.

We are not the only initiative of our kind. Across Africa and Asia, there are other projects asking similar questions about their cultural heritage. Our hope is that we can provoke institutions in North America and Europe to rethink the morality of their collections. We are asking them to account for the violent histories of some of the objects in their collections by labeling their collections more truthfully. We are asking them to return objects that were improperly acquired back to the communities that need them. We are asking them to trust African museums to store objects on behalf of the people of Africa. There can be no collective identity without collective memory. So we are asking for our objects to help us remember who we are.

Thank you.