I want you to imagine that you are a Child Protective Services worker. And you have to respond to a report of child abuse. You walk into a home, unannounced, unexpected, certainly uninvited. The first thing you see is a mattress in the middle of the room, on the floor. Three kids lying on it, asleep. There's a small table nearby with a couple of ashtrays, empty beer cans. Large rat traps are set in the corner, not too far from where the kids lie asleep. So you make a note. A part of your job is walking through the entire home. So you start with the kitchen, where there's very little food. You notice another mattress in the bedroom, on the floor, that the mother shares with her infant child.

Now, generally, at this point, two things may happen. The children are deemed unsafe and removed from the home, and placed in state custody for a specified period of time. Or the children remain with their family and the child welfare system provides help and support.

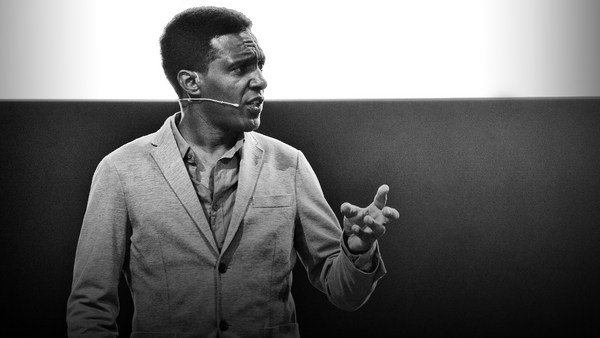

When I was a Child Protective Services worker, I saw things like this all the time. Some far better, some far worse. I asked you to imagine yourself in that home, because I wonder what crossed your mind. What guides your decisions? What's going to impact your opinion of that family? What race, ethnicity, did you think the family was?

I want you to realize that if those children were white, it is more likely that their family stays together after that visit. Research done at the University of Pennsylvania found that white families, on average, have access to more help and more support from the child welfare system. And their cases are less likely to go through a full investigation. But on the other hand, if those kids are black, they are four times more likely to be removed, they spend longer periods of time in foster care, and it's harder to find them a stable foster placement.

Foster care is meant to be an immediate shelter of protection for kids who are at high risk. But it's also a confusing and traumatic exit from the family. Research done at the University of Minnesota found that kids who went through foster care had more behavioral problems and internalized issues than kids who remain with their families while receiving help and support.

The scenario I mentioned earlier is not uncommon. A single mother, living in low-income housing with her four children. And the rats make it almost impossible to keep food, let alone fresh food in the home. Does that mother deserve to have her children taken from her?

Emma Ketteringham, a family court attorney, says that if you live in a poor neighborhood, then you better be a perfect parent. She says that we place unfair, often unreachable standards on parents who are raising their kids with very little money. And their neighborhood and ethnicity impact whether or not their kids are removed. In the two years I spent on the front lines of child welfare, I made high-stakes decisions. And I saw firsthand how my personal values impacted my work.

Now, as social work faculty at Florida State University, I lead an institute that curates the most innovative and effective child welfare research. And research tells us that there are twice as many black kids in foster care, twenty-eight percent, than there are in the general population, 14 percent. And although there are several reasons why, I want to discuss one reason today: implicit bias.

Let's start with "implicit." It's subconscious, something you're not aware of. Bias -- those stereotypes and attitudes that we all have about certain groups of people. So, implicit bias is what lurks in the background of every decision that we make. So how can we fix it?

I have a promising solution that I want to share. Now, in almost every state, there are high numbers of black kids going into foster care. But data revealed that Nassau County, a community in New York, had managed to decrease the number of black kids being removed. And in 2016, I went into that community with my team and led a research study, discovering the use of blind removal meetings.

This is how it works. A case worker responds to a report of child abuse. They go out to the home, but before the children are removed, the case worker must come back to the office and present what they found. But here's the distinction: When they present to the committee, they delete names, ethnicity, neighborhood, race, all identifiable information. They focus on what happened, family strength, relevant history and the parents' ability to protect the child. With that information, the committee makes a recommendation, never knowing the race of the family. Blind removals have made a drastic impact in that community. In 2011, 57 percent of the kids going into foster care were black. But after five years of blind removals, that is down to 21 percent.

(Applause)

Here's what we learned from talking to some of the case workers. "When a family has a history with the department, many of us hold that history against them, even if they're trying to do things differently." "When I see a case from a certain apartment building, neighborhood or zip code, I just automatically think the worst." "Child welfare is very subjective, because it's an emotional field. There's no one who doesn't have emotions around this work. And it's very hard to leave all of your stuff at the door when you do this work. So let's take the subjectivity of race and neighborhood out of it, and you might get different outcomes."

Blind removals seem to be bringing us closer to solving the problem of implicit bias in foster-care decisions. My next step is figuring out how to use artificial intelligence and machine learning to bring this project to scale and make it more accessible to other states. I know we can transform child welfare. We can hold organizations accountable to developing the social consciousness of their employees. We can hold ourselves accountable to making sure our decisions are driven by ethics and safety. Let's imagine a child welfare system that focuses on partnering with parents, empowering families, and no longer see poverty as failure. Let's work together to build a system that wants to make families stronger instead of pulling them apart.

Thank you.

(Applause) (Cheering)