You know, when I was a kid, dreaming about the amazing future that computers could bring, I never thought it would look like this. I snapped this photo in line at a Chipotle, thinking, "Man, what has the world come to?" You know, everyone's stuck in their phones all the time. And then I almost doubled over laughing at myself because there I am, stuck in my phone being judgy about these people, stuck in theirs.

The truth is that we could all benefit from a little less screen time. And so how do we push back and create a healthier relationship to our technology? I've been trying to figure out what comes next, what's the technology that we want to be using?

I spent three years funding deep tech at ARPA-E, and then I moved to Google X, Google's moonshot factory, before creating a spin out called iyo. The last 10 years, diligently, and some may say obsessively, trying to peek beyond the curve. What I think is next is that we need an entirely new kind of computer. One that speaks our language instead of forcing us to speak their language of swipes and clicks. A computer that we can talk to. And not in the way that you speak at Siri with loud, robotic voice commands, but in the way that we talk with each other. So genuine, engaging conversation. So a new kind of natural language computing built on a new kind of compute hardware.

So we've been building this new kind of computer in secret for six years now, and today is the first time that we're talking about it publicly. So this is a prototype “audio computer,” as we call them. And the first thing that you'll see is they don't have a screen. We've got perfectly good screens in our pockets, and we're hoping that we could leave them there or even at home a little bit more often.

So these are not just fancy-looking earbuds. They're an entire computer, and we think they're going to replace some of what we do with the visual computers that we're used to. We've created a new audio-based user interface, which relies on natural language as the input and what we call “auditory space” as the output. And we're hoping that these innovations will help us create a new kind of relationship with computers, where the iyo is more natural, more intuitive. So you can just talk, have a natural-language conversation with all kinds of different powerful audio apps.

So here's a really simple example. Hey, Q.

Voice: Hi, Jason. How are you doing?

Jason Rugolo: Hey, I'm good, I'm doing the TED talk right now.

Voice: You got this, Jason, how can I support you?

JR: I don't know, you know I'm nervous talking in front of this many people.

Voice: Yeah, I know you don't like public speaking. How can I help?

JR: I guess I could use a little bit of encouragement.

Voice: Do you want me to share a positive message from a loved one?

JR: Yeah, that'd be great. Maybe just one, I don't want to bore people.

Voice: Your dad texted, "Good luck today, Jason. I'm so proud of you."

JR: That's awesome, thanks, Q. Can you tell him I said thanks and tell him I'm up on stage right now? He'll get a kick out of that.

Voice: No problem.

JR: So any suggestions for how I could loosen up a little bit?

Voice: Do you want to hear a joke to lighten the mood?

JR: OK, yeah, maybe if it's on theme. Do you know any tech start-up jokes?

Voice: How many start-up founders does it take to change a light bulb?

JR: I don't know, tell me.

Voice: Only one. He just holds it in place, and the world revolves around him.

(Laughter)

JR: OK, sick burn. I'm going to get back to the talk here.

So do you see the difference between those robotic voice commands and just a conversation? Natural language is just more natural. It's intuitive, it's better. So what makes this kind of conversation possible? It's the single most revolutionary breakthrough in the history of information technology. And don't worry, I'm not talking about our devices, although they're pretty cool. And I don't mean LLMs either, which are obviously a building block here. What I'm talking about is something much older. It's the first uniquely human form of communication, the one that we naturally learn as children and has its structure built into our brain. It's the very thing I'm doing right now. Talking.

Spoken language emerged in tandem with the evolution of human consciousness, and to this day, it remains our most efficient and emotionally robust form of communication. Conversation is not just transmitting ideas from one person to another. It's more like thinking together. Modern neuroscientists have pioneered a whole new approach to the brain. It's called second-person neuroscience, and it’s built on the notion that how we think is not isolated. It’s collective, and it happens out loud. Not just through words, but through subtle signals of tone and prosody, your timbre and your pitch and intensity. And neuroscience is just not complete until you add a second person into this full social dynamic. So why can't we have a computer that we can talk with in that way? With that kind of natural language. A computer that has superhuman processing speed. And it has access to the internet. And it’s been trained on the entire written record of human thought. But engages with you like a person would, that understands your intention and that taps into the superpower of human natural language understanding. That's the promise of audio computing.

So think about not just how it can replace many of the things that you do on your phone but actually make them better. So take email, for example. We pull out our phones, we swipe, we scroll, we furiously type with our thumbs. Wouldn't it be better to just sit back with a cup of coffee and to be briefed in a conversation? Or search, search is a big one. It's an incredible technology that made the world a radically better place. But with these audio computers, you can just talk out loud about anything that you want to know. It just feels so normal.

So there's a big difference between giving a voice command to one of the big five voice assistants, which are these structured, predefined choose-your-own-adventure dialogue models that we all have to learn, and I'm sure have all felt that frustration, and just having a real conversation. These natural-language applications can get to know you in the same way that we get to know each other. They build context about our lives just through us talking over time. So later, take out your phone, look at all those apps, all those candy-colored icons, and think about how could you accomplish the same thing but through conversation? Or how could you make it better? You won't be able to do Instagram or TikTok, those apps whose content is mostly visual. But wouldn't it be better to spend a little bit less time in those apps, or just to need your screen a little bit less?

So our goal is to be heads-up and hands-free for a little bit more of the day. You know, just get back into the world. Of course, if the auditory user interface or the AUI, as we call it, is going to really integrate into your life, it has to feel private and convenient to use. So that's why we built it as an all-day wearable for the ear. But your ears are for hearing first and foremost. And so if you're going to wear a computer on them all day, we can't mess that up. In fact, we should probably make that better too.

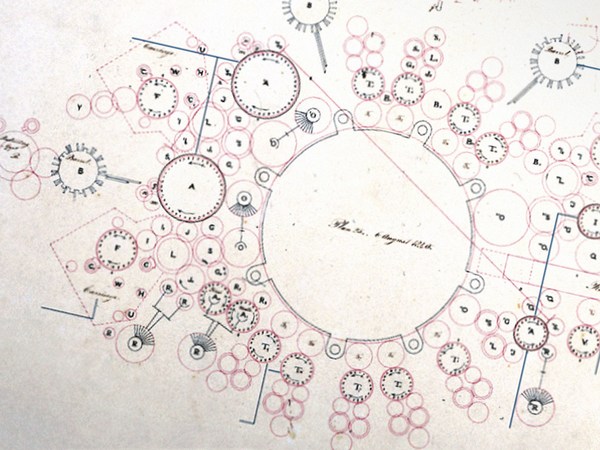

So these audio computers, over the last six grueling years of R and D, became a sort of mixed-reality device. It's like the Apple Vision Pro, but for audio, where we can pass through and we can modify your ambient acoustics, giving you an unprecedented control over your personal soundscape. In order to do mixed-audio reality, we sort of had to hack the auditory system to be able to display sound in ultra-high fidelity, spatially, as if it's all around you. So there's this whole field of research. It’s called psychoacoustics, which we’ve led on for years. We built this giant audio structure. It's a dome with 128 custom speakers coming from all directions, so we could create virtual soundscapes. It's sort of like the Star Trek holodeck, but for audio. And if you're standing in the middle of this and you close your eyes, we can transport you auditorily to anywhere that we want. So we can render a virtual football game, and you feel the energy. Or we can make it sound like you’re in the middle of a bustling city street. And if you’re me, you feel the anxiety. Or standing on a beach with the crashing waves, and you feel the peace. And so it's super cool. I wish everyone could be inside there. Then we ran countless experiments to figure out all the complicated ways that your brain positions sounds in space. Also, we could reverse-engineer those neural algorithms and code them into our software.

So our goal has been to create this experience but right here. Us psychoacousticians call this “virtual auditory space” to distinguish from our real auditory space, which is, you know, the sounds that are all around us. And this is what's necessary to create a compelling mixed audio-reality device.

So it's actually impossible to demonstrate this experience until you hear it with your ears yourself. But to give you an idea, we have tried to simulate it for you. So imagine that you’re sitting in a noisy restaurant, and you're having trouble hearing your friends across the table.

(Overlapping voices, music and noise)

Hey, can you enhance the sounds that are right in front of me?

(People speaking)

(Baby crying)

And can you turn that baby down?

(People talking)

That’s better. I'm still having a little trouble hearing Pedro.

Can you isolate Pedro for me?

Pedro: (Speaking in Spanish)

JR: That's perfect. And, you know, my Spanish is a little rusty. Can I hear Pedro but in English?

Pedro: And at the end of the trip, we came back to the city to visit the historic center.

JR: Hey Shell, close all programs.

(Noise enhances)

Ah, it’s so much worse.

That's pretty cool, right? It's pretty cool.

(Applause)

So what you just heard was a beamforming app, the computational auditory scene analysis app, a machine-learning denoising app, an AI transcription and translation and text-to-speech with style transfer app. The point is that all those audio transformations are done by software.

So we think the possibilities for these audio computers are pretty much endless, and we can't wait to see what the world's developers are going to do here. Like imagine an education app that knows your personal learning style and can teach you with the quality of a world-class professor, on-call anytime. Or like a fitness coach you can summon all day about your diet and exercise, who can also motivate you through conversation and even gamify your workout with some auditory cues. Or, hey, K?

Voice: Hi, Jason. What's up? Hey, if you were going to make an audio app that could be anything, what would it be?

Voice: How about a whoopee cushion that plays a fart sound whenever you sit down?

(Laughter)

JR: Hey, K, if you were going to make an audio app that didn't have anything to do with farts, what would it be?

Voice: Maybe an app that generates personalized soundscapes for relaxation and focus?

JR: That's much better. Alright, it looks like we still have a little fine-tuning to do here.

So the point is, imagination is the only limit to what you can do here. Our goal is not just to create the world's first audio computer, it's to create a truly intuitive computing experience where we're not monetizing your attention or making you captive to a new kind of device, but instead interfacing machines with us in the way that we were born to. So I think it's time for a computer that speaks our language.

Thank you.

(Applause)