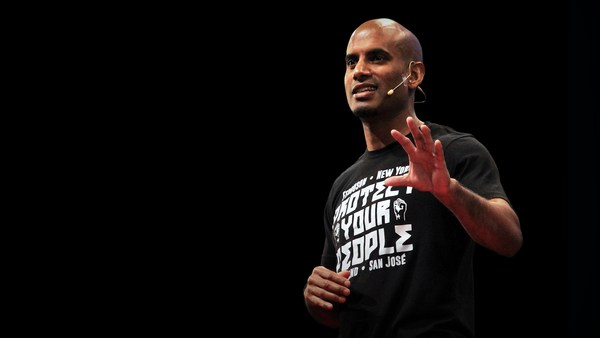

When I look in the mirror today, I see a justice and education scholar at Columbia University, a youth mentor, an activist and a future New York state senator.

(Cheering)

I see all of that and a man who spent a quarter of his life in state prison -- six years, to be exact, starting as a teenager on Rikers Island for an act that nearly cost a man his life. But what got me from there to here wasn't the punishment I faced as a teenager in adult prison or the harshness of our legal system. Instead, it was a learning environment of a classroom that introduced me to something I didn't think was possible for me or our justice system as a whole.

A few weeks before my release on parole, a counselor encouraged me to enroll in a new college course being offered in the prison. It was called Inside Criminal Justice. That seems pretty straightforward, though, right? Well, it turns out, the class would be made up of eight incarcerated men and eight assistant district attorneys. Columbia University psychology professor Geraldine Downey and Manhattan Assistant DA Lucy Lang co-taught the course, and it was the first of its kind.

I can honestly say this wasn't how I imagined starting college. My mind was blown from day one. I assumed all the prosecutors in the room would be white. But I remember walking into the room on the first day of class and seeing three black prosecutors and thinking to myself, "Wow, being a black prosecutor -- that's a thing!"

(Laughter)

By the end of the first session, I was all in. In fact, a few weeks after my release, I found myself doing something I prayed I wouldn't. I walked right back into prison. But thankfully, this time it was just as a student, to join my fellow classmates. And this time, I got to go home when class was over.

In the next session, we talked about what had brought each of us to this point of our lives and into the classroom together. I eventually got comfortable enough to reveal my truth to everyone in the room about where I came from. I talked about how my sisters and I watched our mother suffer years of abuse at the hands of our stepfather, escaping, only to find ourselves living in a shelter. I talked about how I swore an oath to my family to keep them safe. I even explained how I didn't feel like a teenager at 13, but more like a soldier on a mission. And like any soldier, this meant carrying an emotional burden on my shoulders, and I hate to say it, but a gun on my waist. And just a few days after my 17th birthday, that mission completely failed.

As my sister and I were walking to the laundromat, a crowd stopped in front of us. Two girls out of nowhere attacked my sister. Still confused about what was happening, I tried to pull one girl away, and just as I did, I felt something brush across my face. With my adrenaline rushing, I didn't realize a man had leaped out of the crowd and cut me. As I felt warm blood ooze down my face, and watching him raise his knife toward me again, I turned to defend myself and pulled that gun from my waistband and squeezed the trigger. Thankfully, he didn't lose his life that day. My hands shaking and heart racing, I was paralyzed in fear. From that moment, I felt regret that would never leave me.

I learned later on they attacked my sister in a case of mistaken identity, thinking she was someone else. It was terrifying, but clear that I wasn't trained, nor was I qualified, to be the soldier that I thought I needed to be. But in my neighborhood, I only felt safe carrying a weapon.

Now, back in the classroom, after hearing my story, the prosecutors could tell I never wanted to hurt anyone. I just wanted us to make it home. I could literally see the gradual change in each of their faces as they heard story after story from the other incarcerated men in the room. Stories that have trapped many of us within the vicious cycle of incarceration, that most haven't been able to break free of. And sure -- there are people who commit terrible crimes. But the stories of these individuals' lives before they commit those acts were the kinds of stories these prosecutors had never heard.

And when it was their turn to speak -- the prosecutors -- I was surprised, too. They weren't emotionless drones or robocops, preprogrammed to send people to prison. They were sons and daughters, brothers and sisters. But most of all, they were good students. They were ambitious and motivated. And they believed that they could use the power of law to protect people. They were on a mission that I could definitely understand.

Midway through the course, Nick, a fellow incarcerated student, poured out his concern that the prosecutors were tiptoeing around the racial bias and discrimination within our criminal justice system. Now, if you've ever been to prison, you would know it's impossible to talk about justice reform without talking about race. So we silently cheered for Nick and were eager to hear the prosecutors' response. And no, I don't remember who spoke first, but when Chauncey Parker, a senior prosecutor, agreed with Nick and said he was committed to ending the mass incarceration of people of color, I believed him. And I knew we were headed in the right direction. We now started to move as a team. We started exploring new possibilities and uncovering truths about our justice system and how real change happens for us.

For me, it wasn't the mandatory programs inside of the prison. Instead, it was listening to the advice of elders -- men who have been sentenced to spend the rest of their lives in prison. These men helped me reframe my mindset around manhood. And they instilled in me all of their aspirations and goals, in the hopes that I would never return to prison, and that I would serve as their ambassador to the free world. As I talked, I could see the lights turning on for one prosecutor, who said something I thought was obvious: that I had transformed despite my incarceration and not because of it.

It was clear these prosecutors hadn't thought much about what happens to us after they win a conviction. But through the simple process of sitting in a classroom, these lawyers started to see that keeping us locked up didn't benefit our community or us.

Toward the end of the course, the prosecutors were excited, as we talked about our plans for life after being released. But they hadn't realized how rough it was actually going to be. I can literally still see the shock on one of the junior ADA's face when it hit her: the temporary ID given to us with our freedom displayed that we were just released from prison. She hadn't imagined how many barriers this would create for us as we reenter society. But I could also see her genuine empathy for the choice we had to make between coming home to a bed in a shelter or a couch in a relative's overcrowded apartment.

What we learned in the class worked its way into concrete policy recommendations. We presented our proposals to the state Department of Corrections commissioner and to the Manhattan DA, at our graduation in a packed Columbia auditorium. As a team, I couldn't have imagined a more memorable way to conclude our eight weeks together.

And just 10 months after coming home from prison, I again found myself in a strange room, invited by the commissioner of NYPD to share my perspective at a policing summit. And while speaking, I recognized a familiar face in the audience. It was the attorney who prosecuted my case. Seeing him, I thought about our days in the courtroom seven years earlier, as I listened to him recommend a long prison sentence, as if my young life was meaningless and had no potential. But this time, the circumstances were different. I shook off my thoughts and walked over to shake his hand. He looked happy to see me. Surprised, but happy. He acknowledged how proud he was about being in that room with me, and we began a conversation about working together to improve the conditions of our community.

And so today, I carry all of these experiences with me, as I develop the Justice Ambassadors Youth Council at Columbia University, bringing young New Yorkers -- some who have already spent time locked up and others who are still enrolled in high school -- together with city officials. And in this classroom, everyone will brainstorm ideas about improving the lives of our city's most vulnerable youth before they get tried within the criminal justice system.

This is possible if we do the work. Our society and justice system has convinced us that we can lock up our problems and punish our way out of social challenges. But that's not real. Imagine with me for a second a future where no one can become a prosecutor, a judge, a cop or even a parole officer without first sitting in a classroom to learn from and connect with the very people whose lives will be in their hands.

I'm doing my part to promote the power of conversations and the need for collaborations. It is through education that we will arrive at a truth that is inclusive and unites us all in the pursuit of justice. For me, it was a brand-new conversation and a new kind of classroom that showed me how both my mindset and our criminal justice system could be transformed.

They say the truth shall set you free. But I believe it's education and communication.

Thank you.

(Applause)