To give me an idea of how many of you here may find what I'm about to tell you of practical value, let me ask you please to raise your hands: Who here is either over 65 years old or hopes to live past age 65 or has parents or grandparents who did live or have lived past 65, raise your hands please. (Laughter)

Okay. You are the people to whom my talk will be of practical value. (Laughter) The rest of you won't find my talk personally relevant, but I think that you will still find the subject fascinating.

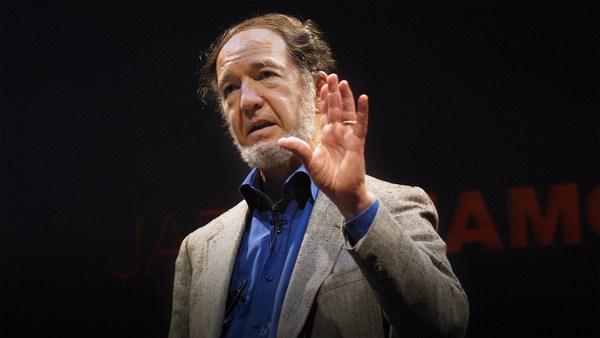

I'm going to talk about growing older in traditional societies. This subject constitutes just one chapter of my latest book, which compares traditional, small, tribal societies with our large, modern societies, with respect to many topics such as bringing up children, growing older, health, dealing with danger, settling disputes, religion and speaking more than one language.

Those tribal societies, which constituted all human societies for most of human history, are far more diverse than are our modern, recent, big societies. All big societies that have governments, and where most people are strangers to each other, are inevitably similar to each other and different from tribal societies. Tribes constitute thousands of natural experiments in how to run a human society. They constitute experiments from which we ourselves may be able to learn. Tribal societies shouldn't be scorned as primitive and miserable, but also they shouldn't be romanticized as happy and peaceful. When we learn of tribal practices, some of them will horrify us, but there are other tribal practices which, when we hear about them, we may admire and envy and wonder whether we could adopt those practices ourselves.

Most old people in the U.S. end up living separately from their children and from most of their friends of their earlier years, and often they live in separate retirements homes for the elderly, whereas in traditional societies, older people instead live out their lives among their children, their other relatives, and their lifelong friends. Nevertheless, the treatment of the elderly varies enormously among traditional societies, from much worse to much better than in our modern societies.

At the worst extreme, many traditional societies get rid of their elderly in one of four increasingly direct ways: by neglecting their elderly and not feeding or cleaning them until they die, or by abandoning them when the group moves, or by encouraging older people to commit suicide, or by killing older people. In which tribal societies do children abandon or kill their parents? It happens mainly under two conditions. One is in nomadic, hunter-gather societies that often shift camp and that are physically incapable of transporting old people who can't walk when the able-bodied younger people already have to carry their young children and all their physical possessions. The other condition is in societies living in marginal or fluctuating environments, such as the Arctic or deserts, where there are periodic food shortages, and occasionally there just isn't enough food to keep everyone alive. Whatever food is available has to be reserved for able-bodied adults and for children. To us Americans, it sounds horrible to think of abandoning or killing your own sick wife or husband or elderly mother or father, but what could those traditional societies do differently? They face a cruel situation of no choice. Their old people had to do it to their own parents, and the old people know what now is going to happen to them.

At the opposite extreme in treatment of the elderly, the happy extreme, are the New Guinea farming societies where I've been doing my fieldwork for the past 50 years, and most other sedentary traditional societies around the world. In those societies, older people are cared for. They are fed. They remain valuable. And they continue to live in the same hut or else in a nearby hut near their children, relatives and lifelong friends.

There are two main sets of reasons for this variation among societies in their treatment of old people. The variation depends especially on the usefulness of old people and on the society's values.

First, as regards usefulness, older people continue to perform useful services. One use of older people in traditional societies is that they often are still effective at producing food. Another traditional usefulness of older people is that they are capable of babysitting their grandchildren, thereby freeing up their own adult children, the parents of those grandchildren, to go hunting and gathering food for the grandchildren. Still another traditional value of older people is in making tools, weapons, baskets, pots and textiles. In fact, they're usually the people who are best at it. Older people usually are the leaders of traditional societies, and the people most knowledgeable about politics, medicine, religion, songs and dances.

Finally, older people in traditional societies have a huge significance that would never occur to us in our modern, literate societies, where our sources of information are books and the Internet. In contrast, in traditional societies without writing, older people are the repositories of information. It's their knowledge that spells the difference between survival and death for their whole society in a time of crisis caused by rare events for which only the oldest people alive have had experience. Those, then, are the ways in which older people are useful in traditional societies. Their usefulness varies and contributes to variation in the society's treatment of the elderly.

The other set of reasons for variation in the treatment of the elderly is the society's cultural values. For example, there's particular emphasis on respect for the elderly in East Asia, associated with Confucius' doctrine of filial piety, which means obedience, respect and support for elderly parents. Cultural values that emphasize respect for older people contrast with the low status of the elderly in the U.S. Older Americans are at a big disadvantage in job applications. They're at a big disadvantage in hospitals. Our hospitals have an explicit policy called age-based allocation of healthcare resources. That sinister expression means that if hospital resources are limited, for example if only one donor heart becomes available for transplant, or if a surgeon has time to operate on only a certain number of patients, American hospitals have an explicit policy of giving preference to younger patients over older patients on the grounds that younger patients are considered more valuable to society because they have more years of life ahead of them, even though the younger patients have fewer years of valuable life experience behind them. There are several reasons for this low status of the elderly in the U.S. One is our Protestant work ethic which places high value on work, so older people who are no longer working aren't respected. Another reason is our American emphasis on the virtues of self-reliance and independence, so we instinctively look down on older people who are no longer self-reliant and independent. Still a third reason is our American cult of youth, which shows up even in our advertisements. Ads for Coca-Cola and beer always depict smiling young people, even though old as well as young people buy and drink Coca-Cola and beer. Just think, what's the last time you saw a Coke or beer ad depicting smiling people 85 years old? Never. Instead, the only American ads featuring white-haired old people are ads for retirement homes and pension planning.

Well, what has changed in the status of the elderly today compared to their status in traditional societies? There have been a few changes for the better and more changes for the worse. Big changes for the better include the fact that today we enjoy much longer lives, much better health in our old age, and much better recreational opportunities. Another change for the better is that we now have specialized retirement facilities and programs to take care of old people. Changes for the worse begin with the cruel reality that we now have more old people and fewer young people than at any time in the past. That means that all those old people are more of a burden on the few young people, and that each old person has less individual value. Another big change for the worse in the status of the elderly is the breaking of social ties with age, because older people, their children, and their friends, all move and scatter independently of each other many times during their lives. We Americans move on the average every five years. Hence our older people are likely to end up living distant from their children and the friends of their youth. Yet another change for the worse in the status of the elderly is formal retirement from the workforce, carrying with it a loss of work friendships and a loss of the self-esteem associated with work. Perhaps the biggest change for the worse is that our elderly are objectively less useful than in traditional societies. Widespread literacy means that they are no longer useful as repositories of knowledge. When we want some information, we look it up in a book or we Google it instead of finding some old person to ask. The slow pace of technological change in traditional societies means that what someone learns there as a child is still useful when that person is old, but the rapid pace of technological change today means that what we learn as children is no longer useful 60 years later. And conversely, we older people are not fluent in the technologies essential for surviving in modern society. For example, as a 15-year-old, I was considered outstandingly good at multiplying numbers because I had memorized the multiplication tables and I know how to use logarithms and I'm quick at manipulating a slide rule. Today, though, those skills are utterly useless because any idiot can now multiply eight-digit numbers accurately and instantly with a pocket calculator. Conversely, I at age 75 am incompetent at skills essential for everyday life. My family's first TV set in 1948 had only three knobs that I quickly mastered: an on-off switch, a volume knob, and a channel selector knob. Today, just to watch a program on the TV set in my own house, I have to operate a 41-button TV remote that utterly defeats me. I have to telephone my 25-year-old sons and ask them to talk me through it while I try to push those wretched 41 buttons.

What can we do to improve the lives of the elderly in the U.S., and to make better use of their value? That's a huge problem. In my remaining four minutes today, I can offer just a few suggestions. One value of older people is that they are increasingly useful as grandparents for offering high-quality childcare to their grandchildren, if they choose to do it, as more young women enter the workforce and as fewer young parents of either gender stay home as full-time caretakers of their children. Compared to the usual alternatives of paid babysitters and day care centers, grandparents offer superior, motivated, experienced child care. They've already gained experience from raising their own children. They usually love their grandchildren, and are eager to spend time with them. Unlike other caregivers, grandparents don't quit their job because they found another job with higher pay looking after another baby. A second value of older people is paradoxically related to their loss of value as a result of changing world conditions and technology. At the same time, older people have gained in value today precisely because of their unique experience of living conditions that have now become rare because of rapid change, but that could come back. For example, only Americans now in their 70s or older today can remember the experience of living through a great depression, the experience of living through a world war, and agonizing whether or not dropping atomic bombs would be more horrible than the likely consequences of not dropping atomic bombs. Most of our current voters and politicians have no personal experience of any of those things, but millions of older Americans do. Unfortunately, all of those terrible situations could come back. Even if they don't come back, we have to be able to plan for them on the basis of the experience of what they were like. Older people have that experience. Younger people don't.

The remaining value of older people that I'll mention involves recognizing that while there are many things that older people can no longer do, there are other things that they can do better than younger people. A challenge for society is to make use of those things that older people are better at doing. Some abilities, of course, decrease with age. Those include abilities at tasks requiring physical strength and stamina, ambition, and the power of novel reasoning in a circumscribed situation, such as figuring out the structure of DNA, best left to scientists under the age of 30. Conversely, valuable attributes that increase with age include experience, understanding of people and human relationships, ability to help other people without your own ego getting in the way, and interdisciplinary thinking about large databases, such as economics and comparative history, best left to scholars over the age of 60. Hence older people are much better than younger people at supervising, administering, advising, strategizing, teaching, synthesizing, and devising long-term plans. I've seen this value of older people with so many of my friends in their 60s, 70s, 80s and 90s, who are still active as investment managers, farmers, lawyers and doctors. In short, many traditional societies make better use of their elderly and give their elderly more satisfying lives than we do in modern, big societies.

Paradoxically nowadays, when we have more elderly people than ever before, living healthier lives and with better medical care than ever before, old age is in some respects more miserable than ever before. The lives of the elderly are widely recognized as constituting a disaster area of modern American society. We can surely do better by learning from the lives of the elderly in traditional societies. But what's true of the lives of the elderly in traditional societies is true of many other features of traditional societies as well. Of course, I'm not advocating that we all give up agriculture and metal tools and return to a hunter-gatherer lifestyle. There are many obvious respects in which our lives today are far happier than those in small, traditional societies. To mention just a few examples, our lives are longer, materially much richer, and less plagued by violence than are the lives of people in traditional societies. But there are also things to be admired about people in traditional societies, and perhaps to be learned from them. Their lives are usually socially much richer than our lives, although materially poorer. Their children are more self-confident, more independent, and more socially skilled than are our children. They think more realistically about dangers than we do. They almost never die of diabetes, heart disease, stroke, and the other noncommunicable diseases that will be the causes of death of almost all of us in this room today. Features of the modern lifestyle predispose us to those diseases, and features of the traditional lifestyle protect us against them.

Those are just some examples of what we can learn from traditional societies. I hope that you will find it as fascinating to read about traditional societies as I found it to live in those societies.

Thank you.

(Applause)