When you think of a war reporter, who do you picture? Someone like this? Or someone like this? Maybe him? Or maybe someone like this? Her?

I'm asked all the time, what does it feel like to be one of the only women working in your field? How do you cope in such a male-dominated industry as frontline war reporting? The question continues to baffle me. Women have been doing this work for over a century. From Martha Gellhorn to Clare Hollingworth, from Marguerite Higgins to Christiane Amanpour. In fact, one of the reasons I wanted to become a foreign correspondent and a war reporter was watching these women in the field, reporting. They were professional role models, every evening at 6pm on the news when I was a little girl in my living room, growing up in Northern Ireland. Women reporting from all over the world on the BBC, and the men were listening to them.

(Laughter)

(Applause)

Today when I go to war zones, very often it is a majority of women who are actually reporting there. So when I point out that I'm no trailblazer, the next question to come is, why? Why are so many women becoming war reporters?

(Laughter)

My answer to this question is quick and easy. Because we are really, really good at it.

(Applause)

So good, in fact, that war reporting today, the very nature of reporting, and therefore how wars are perceived by those we report to, has been changed by women taking the lead. The types of stories that are covered, the angles that are taken have been shaped by the fact that more and more women are reporting them. The debate over whether or not men and women are different in the workplace, whether we should highlight these differences, whether it matters, has gone on for years. In war reporting, it hasn't always been a given that we should lean into our gender lens. For years, women who have fought to be at the front line, to be given assignments in major wars, often by male editors, have felt the pressure not to be pigeonholed into covering "women's issues" or "softer topics." Who here hasn’t felt this way, uf you’ve ever been one of the first women in a male-dominated field, that pressure to be one of the guys, to not be too emotional?

I was first struck by the number of female war reporters when covering the war in Syria. It was one of my first ever major assignments for a TV news network. I was to be smuggled across the border from Lebanon into a rebel stronghold in early 2012. The activists who were smuggling journalists in typically took us one at a time. The journalist who preceded me was a female correspondent for "El Pais" newspaper in Spain. Two journalists came after me together. One of them a female correspondent for CNN, the other a female correspondent for "The Times of London" called Marie Colvin. Colvin wouldn't make it out of Syria alive. She was killed by the Assad forces while reporting on their war crimes. Yes. This is dangerous work.

When I moved to Beirut in 2014, the war in Syria raged on, and the Lebanese capital had become a hub for international journalists who were living there and covering the war across the border. I was struck by how many of them were women. More obviously, of course, those who were on-camera TV reporters. But a huge amount, in many cases, the majority of print reporters as well, were women. Walk into any bar in Beirut back then frequented by international and Lebanese journalists and you would have been faced with a small crowd of smiling, waving female foreign correspondents catching up between assignments and deadlines.

Now while there was plenty of camaraderie on the assignment in Syria, the war in Afghanistan in recent years has felt different. The US press, as the war came to an end, was less interested in that conflict beyond what it meant for the geopolitics in the region or US foreign affairs and national security. The few times that I did bump into female journalists there, the few times I bumped into any journalists there, they were almost always women.

One day, about six months before Kabul fell to the Taliban, I went out to visit a checkpoint on the outskirts of Kabul. At the time, there was already concern about whether or not the Afghan forces could hold off a Taliban attack on the capital. Shortly after I arrived, another crew came, and the soldiers got very excited. This was a news team from TOLO TV, and the correspondent was one of the most famous journalists in Afghanistan. Her name was Anisa Shaheed. The soldiers crowded around, trying to get a photograph with her in a selfie. So did I.

(Laughter)

This sort of thing happened all the time in Afghanistan. Women bumping into one another, reporting on that war. Between us, we covered civilian casualties, women's rights, access to education and the hopes and dreams Afghans had for their future. Of course, we also covered the major news of the day, the politics, the frontline fighting and the conditions for the Afghan security forces. But we relentlessly interviewed civilians, profiling doctors and teachers and business people, many of them women, elevating civilian voices.

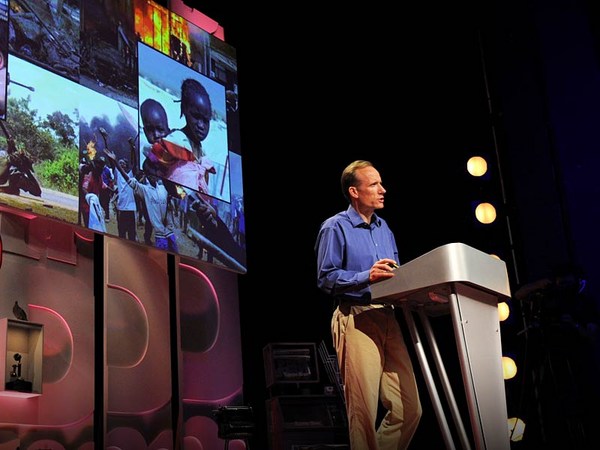

In the early days of the war in Afghanistan, while vital, risky and important work was being done, very often the kind of images that were making it out of the conflict looked largely like this. As the war came to an end in its final years, the predominant images were increasingly looking like this. Now, of course, Afghanistan had evolved and changed, but so too had those who were carrying the lens through which the world would see it.

Now, none of this is to negate the vital and important work our male colleagues do in the field. Male journalists have been and continue to do brilliant reporting. But what I want to draw attention to is the rapid growth of female journalists in the field and also the impact they've had on the reporting itself that has come out of war zones around the world. Now, when wars break out, it's humanizing images like this that are predominantly broadcast around the world that show how families and communities are impacted by war. They're no longer the exception. They are the norm.

When Vladimir Putin invaded Ukraine in February 2022, the images that were broadcast around the world were of families saying goodbye to fathers in Kyiv train station, children clutching their pets in underground bunkers and the elderly clamoring over broken bridges, trying to escape. It was these human images that connected millions of people to what it was really like there, for people to live through that war. Many of the stories coming from the war in Ukraine were reported by women. Earlier this year, the Ukraine reporting team for "The Washington Post" was awarded an award for courage in journalism for its huge, female-led teams of editors, writers, photographers and journalists.

And who could forget the women of Iran, who not only are protesting against the repressive edicts of their government, but leading the fight to make sure the world covers their story. Every day, women activists and journalists in Iran fight to make sure, and risk their lives, to make sure the images and videos of their struggle, their protests and the crackdown against them, make it out. It's those voices that I remember most, filling my apartment in New York City in the middle of the night. For journalists like me and many others who cannot access the country, we have been able to make contact with these women. They use slow internet connections and outlawed VPNs.

Now, if you're going to report from a war zone, female camaraderie does help, too. When Kabul fell to the Taliban in August 2021, I was part of a small group of international journalists who decided to stay at the airport and continue on their reporting on the evacuations. Part of that group included a female producer for British TV, as well as a female correspondent for Danish television. Between the three of us, we shared everything from a precious clean shirt to eyeliner and hairbrushes. We may have been reporting from a war zone, but we all knew the pressures of being a woman who had to be on TV that night.

And I know what a lot of people wonder. What about the tough stuff? What about the sleeping in trenches, lugging gear, coming under fire and the generally rough living conditions? I get asked all the time, how do you take a shower? My male colleagues never get asked. It seems absurd that we have to keep answering these questions. But again and again, women have proven that they are just as tough, brave and stoic when faced with the physical and emotional challenges of reporting from war zones as the men. Why wouldn't we be? We've been doing it for decades, since the Spanish Civil War, World War II and the War in Vietnam, even though women at the time were a tiny minority.

Since those who came before us nudged the door open just enough, the number of women who have been able to in the last 20 years get assigned stories as editors, photographers, writers and broadcasters in major war zones has massively increased. We've not only increased in numbers, but crucially, we've increased in our confidence to tell stories that harnesses our unique perspective and our own unique strengths. Now many of the things we may have feared in the past would be held against us, our compassion, our empathy and our focus on civilian lives have become our greatest strengths.

We're also seeing that reflected in our male colleagues' reporting as well. A focus on how war impacts communities and families more broadly has become the norm. We are not just good at this job because we are empathetic and softer and have a really good eye for a human story. We're good at this reporting because we're soft and empathetic and strong and tough and brave. We have extraordinary range, and it is female range that is added to the range of voices and stories and faces that are making it out and in front of the public from war zones today.

When the world is presented to you, not just in television and radio and print and magazine, by a male gaze but by a female reporter as well, our attitudes to the outside world change, too. We feel more connected. We can see beyond the statistics, the politics and just the war-fighting. We as journalists are at heart communicators, and it is female reporting that is helping the world better commune.

Thank you.

(Applause)