This is Charley Williams. He was 94 when this photograph was taken. In the 1930s, Roosevelt put thousands and thousands of Americans back to work by building bridges and infrastructure and tunnels, but he also did something interesting, which was to hire a few hundred writers to scour America to capture the stories of ordinary Americans. Charley Williams, a poor sharecropper, wouldn't ordinarily be the subject of a big interview, but Charley had actually been a slave until he was 22 years old. And the stories that were captured of his life make up one of the crown jewels of histories, of human-lived experiences filled with ex-slaves.

Anna Deavere Smith famously said that there's a literature inside of each of us, and three generations later, I was part of a project called StoryCorps, which set out to capture the stories of ordinary Americans by setting up a soundproof booth in public spaces. The idea is very, very simple. You go into these booths, you interview your grandmother or relative, you leave with a copy of the interview and an interview goes into the Library of Congress. It's essentially a way to make a national oral histories archive one conversation at a time. And the question is, who do you want to remember -- if you had just 45 minutes with your grandmother? What's interesting, in conversations with the founder, Dave Isay, we always actually talked about this as a little bit of a subversive project, because when you think about it, it's actually not really about the stories that are being told, it's about listening, and it's about the questions that you get to ask, questions that you may not have permission to on any other day. I'm going to play you just a couple of quick excerpts from the project.

[Jesus Melendez talking about poet Pedro Pietri's final moments]

Jesus Melendez: We took off, and as we were ascending, before we had leveled off, our level-off point was 45,000 feet, so before we had leveled off, Pedro began leaving us, and the beauty about it is that I believe that there's something after life. You can see it in Pedro.

[Danny Perasa to his wife Annie Perasa married 26 years]

Danny Perasa: See, the thing of it is, I always feel guilty when I say "I love you" to you, and I say it so often. I say it to remind you that as dumpy as I am, it's coming from me, it's like hearing a beautiful song from a busted old radio, and it's nice of you to keep the radio around the house.

(Laughter)

[Michael Wolmetz with his girlfriend Debora Brakarz]

Michael Wolmetz: So this is the ring that my father gave to my mother, and we can leave it there. And he saved up and he purchased this, and he proposed to my mother with this, and so I thought that I would give it to you so that he could be with us for this also. So I'm going to share a mic with you right now, Debora. Where's the right finger? Debora Brakarz: (Crying) MW: Debora, will you please marry me? DB: Yes. Of course. I love you. (Kissing) MW: So kids, this is how your mother and I got married, in a booth in Grand Central Station with my father's ring. My grandfather was a cab driver for 40 years. He used to pick people up here every day. So it seems right.

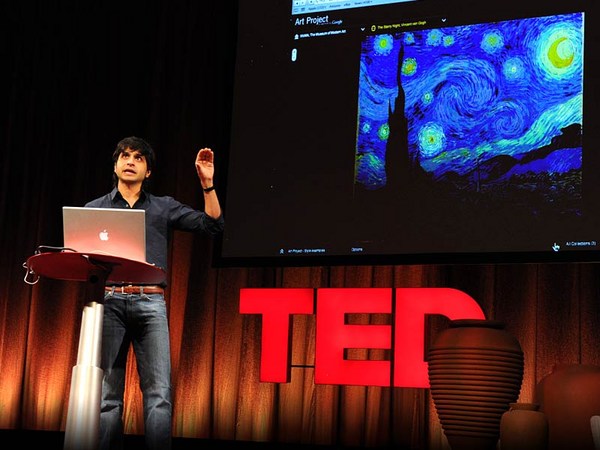

Jake Barton: So I have to say I did not actually choose those individual samples to make you cry because they all make you cry. The entire project is predicated on this act of love which is listening itself. And that motion of building an institution out of a moment of conversation and listening is actually a lot of what my firm, Local Projects, is doing with our engagements in general. So we're a media design firm, and we're working with a broad array of different institutions building media installations for museums and public spaces.

Our latest engagement is the Cleveland Museum of Art, which we've created an engagement called Gallery One for. And Gallery One is an interesting project because it started with this massive, $350 million expansion for the Cleveland Museum of Art, and we actually brought in this piece specifically to grow new capacity, new audiences, at the same time that the museum itself is growing.

Glenn Lowry, the head of MoMA, put it best when he said, "We want visitors to actually cease being visitors. Visitors are transient. We want people who live here, people who have ownership."

And so what we're doing is making a broad array of different ways for people to actually engage with the material inside of these galleries, so you can still have a traditional gallery experience, but if you're interested, you can actually engage with any individual artwork and see the original context from where it's from, or manipulate the work itself. So, for example, you can click on this individual lion head, and this is where it originated from, 1300 B.C. Or this individual piece here, you can see the actual bedroom. It really changes the way you think about this type of a tempera painting. This is one of my favorites because you see the studio itself. This is Rodin's bust. You get the sense of this incredible factory for creativity. And it makes you think about literally the hundreds or thousands of years of human creativity and how each individual artwork stands in for part of that story. This is Picasso, of course embodying so much of it from the 20th century.

And so our next interface, which I'll show you, actually leverages that idea of this lineage of creativity. It's an algorithm that actually allows you to browse the actual museum's collection using facial recognition. So this person's making different faces, and it's actually drawing forth different objects from the collection that connect with exactly how she's looking. And so you can imagine that, as people are performing inside of the museum itself, you get this sense of this emotional connection, this way in which our face connects with the thousands and tens of thousands of years. This is an interface that actually allows you to draw and then draws forth objects using those same shapes. So more and more we're trying to find ways for people to actually author things inside of the museums themselves, to be creative even as they're looking at other people's creativity and understanding them.

So in this wall, the collections wall, you can actually see all 3,000 artworks all at the same time, and you can actually author your own individual walking tours of the museum, so you can share them, and someone can take a tour with the museum director or a tour with their little cousin.

But all the while that we've been working on this engagement for Cleveland, we've also been working in the background on really our largest engagement to date, and that's the 9/11 Memorial and Museum.

So we started in 2006 as part of a team with Thinc Design to create the original master plan for the museum, and then we've done all the media design both for the museum and the memorial and then the media production. So the memorial opened in 2011, and the museum's going to open next year in 2014. And you can see from these images, the site is so raw and almost archaeological. And of course the event itself is so recent, somewhere between history and current events, it was a huge challenge to imagine how do you actually live up to a space like this, an event like this, to actually tell that story.

And so what we started with was really a new way of thinking about building an institution, through a project called Make History, which we launched in 2009. So it's estimated that a third of the world watched 9/11 live, and a third of the world heard about it within 24 hours, making it really by nature of when it happened, this unprecedented moment of global awareness. And so we launched this to capture the stories from all around the world, through video, through photos, through written history, and so people's experiences on that day, which was, in fact, this huge risk for the institution to make its first move this open platform. But that was coupled together with this oral histories booth, really the simplest we've ever made, where you locate yourself on a map. It's in six languages, and you can tell your own story about what happened to you on that day. And when we started seeing the incredible images and stories that came forth from all around the world -- this is obviously part of the landing gear -- we really started to understand that there was this amazing symmetry between the event itself, between the way that people were telling the stories of the event, and how we ourselves needed to tell that story.

This image in particular really captured our attention at the time, because it so much sums up that event. This is a shot from the Brooklyn-Battery Tunnel. There's a firefighter that's stuck, actually, in traffic, and so the firefighters themselves are running a mile and a half to the site itself with upwards of 70 pounds of gear on their back. And we got this amazing email that said, "While viewing the thousands of photos on the site, I unexpectedly found a photo of my son. It was a shock emotionally, yet a blessing to find this photo," and he was writing because he said, "I'd like to personally thank the photographer for posting the photo, as it meant more than words can describe to me to have access to what is probably the last photo ever taken of my son."

And it really made us recognize what this institution needed to be in order to actually tell that story. We can't have just a historian or a curator narrating objectively in the third person about an event like that, when you have the witnesses to history who are going to make their way through the actual museum itself.

And so we started imagining the museum, along with the creative team at the museum and the curators, thinking about how the first voice that you would hear inside the museum would actually be of other visitors. And so we created this idea of an opening gallery called We Remember. And I'll just play you part of a mockup of it, but you get a sense of what it's like to actually enter into that moment in time and be transported back in history.

(Video) Voice 1: I was in Honolulu, Hawaii. Voice 2: I was in Cairo, Egypt.

Voice 3: Sur les Champs-Élysées, à Paris. Voice 4: In college, at U.C. Berkeley.

Voice 5: I was in Times Square. Voice 6: São Paolo, Brazil.

(Multiple voices)

Voice 7: It was probably about 11 o'clock at night.

Voice 8: I was driving to work at 5:45 local time in the morning.

Voice 9: We were actually in a meeting when someone barged in and said, "Oh my God, a plane has just crashed into the World Trade Center."

Voice 10: Trying to frantically get to a radio.

Voice 11: When I heard it over the radio --

Voice 12: Heard it on the radio.

(Multiple voices)

Voice 13: I got a call from my father. Voice 14: The phone rang, it woke me up. My business partner told me to turn on the television.

Voice 15: So I switched on the television.

Voice 16: All channels in Italy were displaying the same thing.

Voice 17: The Twin Towers. Voice 18: The Twin Towers.

JB: And you move from there into that open, cavernous space. This is the so-called slurry wall. It's the original, excavated wall at the base of the World Trade Center that withstood the actual pressure from the Hudson River for a full year after the event itself. And so we thought about carrying that sense of authenticity, of presence of that moment into the actual exhibition itself. And we tell the stories of being inside the towers through that same audio collage, so you're hearing people literally talking about seeing the planes as they make their way into the building, or making their way down the stairwells. And as you make your way into the exhibition where it talks about the recovery, we actually project directly onto these moments of twisted steel all of the experiences from people who literally excavated on top of the pile itself. And so you can hear oral histories -- so people who were actually working the so-called bucket brigades as you're seeing literally the thousands of experiences from that moment.

And as you leave that storytelling moment understanding about 9/11, we then turn the museum back into a moment of listening and actually talk to the individual visitors and ask them their own experiences about 9/11. And we ask them questions that are actually not really answerable, the types of questions that 9/11 itself draws forth for all of us. And so these are questions like, "How can a democracy balance freedom and security?" "How could 9/11 have happened?" "And how did the world change after 9/11?"

And so these oral histories, which we've actually been capturing already for years, are then mixed together with interviews that we're doing with people like Donald Rumsfeld, Bill Clinton, Rudy Giuliani, and you mix together these different players and these different experiences, these different reflection points about 9/11. And suddenly the institution, once again, turns into a listening experience. So I'll play you just a short excerpt of a mockup that we made of a couple of these voices, but you really get a sense of the poetry of everyone's reflection on the event.

(Video) Voice 1: 9/11 was not just a New York experience.

Voice 2: It's something that we shared, and it's something that united us.

Voice 3: And I knew when I saw that, people who were there that day who immediately went to help people known and unknown to them was something that would pull us through.

Voice 4: All the outpouring of affection and emotion that came from our country was something really that will forever, ever stay with me.

Voice 5: Still today I pray and think about those who lost their lives, and those who gave their lives to help others, but I'm also reminded of the fabric of this country, the love, the compassIon, the strength, and I watched a nation come together in the middle of a terrible tragedy.

JB: And so as people make their way out of the museum, reflecting on the experience, reflecting on their own thoughts of it, they then move into the actual space of the memorial itself, because they've gone back up to grade, and we actually got involved in the memorial after we'd done the museum for a few years. The original designer of the memorial, Michael Arad, had this image in his mind of all the names appearing undifferentiated, almost random, really a poetic reflection on top of the nature of a terrorism event itself, but it was a huge challenge for the families, for the foundation, certainly for the first responders, and there was a negotiation that went forth and a solution was found to actually create not an order in terms of chronology, or in terms of alphabetical, but through what's called meaningful adjacency. So these are groupings of the names themselves which appear undifferentiated but actually have an order, and we, along with Jer Thorp, created an algorithm to take massive amounts of data to actually start to connect together all these different names themselves. So this is an image of the actual algorithm itself with the names scrambled for privacy, but you can see that these blocks of color are actually the four different flights, the two different towers, the first responders, and you can actually see within that different floors, and then the green lines are the interpersonal connections that were requested by the families themselves. And so when you go to the memorial, you can actually see the overarching organization inside of the individual pools themselves. You can see the way that the geography of the event is reflected inside of the memorial, and you can search for an individual name, or in this case an employer, Cantor Fitzgerald, and see the way in which all of those names, those hundreds of names, are actually organized onto the memorial itself, and use that to navigate the memorial. And more importantly, when you're actually at the site of the memorial, you can see those connections. You can see the relationships between the different names themselves. So suddenly what is this undifferentiated, anonymous group of names springs into reality as an individual life. In this case, Harry Ramos, who was the head trader at an investment bank, who stopped to aid Victor Wald on the 55th floor of the South Tower. And Ramos told Wald, according to witnesses, "I'm not going to leave you." And Wald's widow requested that they be listed next to each other.

Three generations ago, we had to actually get people to go out and capture the stories for common people. Today, of course, there's an unprecedented amount of stories for all of us that are being captured for future generations. And this is our hope, that's there's poetry inside of each of our stories.

Thank you very much.

(Applause)