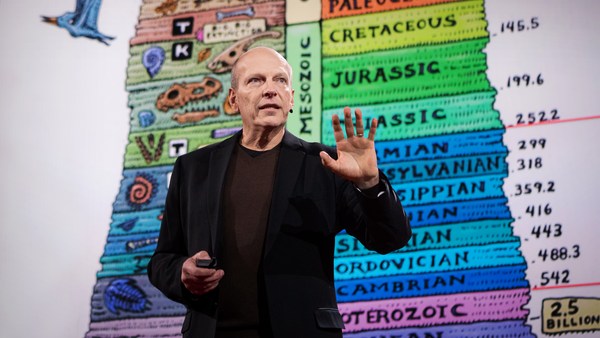

When I was growing up in Montana, I had two dreams. I wanted to be a paleontologist, a dinosaur paleontologist, and I wanted to have a pet dinosaur. And so that's what I've been striving for all of my life. I was very fortunate early in my career. I was fortunate in finding things. I wasn't very good at reading things. In fact, I don't read much of anything. I am extremely dyslexic, and so reading is the hardest thing I do. But instead, I go out and I find things. Then I just pick things up. I basically practice for finding money on the street. (Laughter) And I wander about the hills, and I have found a few things.

And I have been fortunate enough to find things like the first eggs in the Western hemisphere and the first baby dinosaurs in nests, the first dinosaur embryos and massive accumulations of bones. And it happened to be at a time when people were just starting to begin to realize that dinosaurs weren't the big, stupid, green reptiles that people had thought for so many years. People were starting to get an idea that dinosaurs were special.

And so, at that time, I was able to make some interesting hypotheses along with my colleagues. We were able to actually say that dinosaurs -- based on the evidence we had -- that dinosaurs built nests and lived in colonies and cared for their young, brought food to their babies and traveled in gigantic herds. So it was pretty interesting stuff. I have gone on to find more things and discover that dinosaurs really were very social. We have found a lot of evidence that dinosaurs changed from when they were juveniles to when they were adults. The appearance of them would have been different -- which it is in all social animals. In social groups of animals, the juveniles always look different than the adults. The adults can recognize the juveniles; the juveniles can recognize the adults. And so we're making a better picture of what a dinosaur looks like. And they didn't just all chase Jeeps around.

(Laughter)

But it is that social thing that I guess attracted Michael Crichton. And in his book, he talked about the social animals. And then Steven Spielberg, of course, depicts these dinosaurs as being very social creatures. The theme of this story is building a dinosaur, and so we come to that part of "Jurassic Park." Michael Crichton really was one of the first people to talk about bringing dinosaurs back to life. You all know the story, right. I mean, I assume everyone here has seen "Jurassic Park."

If you want to make a dinosaur, you go out, you find yourself a piece of petrified tree sap -- otherwise known as amber -- that has some blood-sucking insects in it, good ones, and you get your insect and you drill into it and you suck out some DNA, because obviously all insects that sucked blood in those days sucked dinosaur DNA out. And you take your DNA back to the laboratory and you clone it. And I guess you inject it into maybe an ostrich egg, or something like that, and then you wait, and, lo and behold, out pops a little baby dinosaur. And everybody's happy about that. (Laughter) And they're happy over and over again. They keep doing it; they just keep making these things. And then, then, then, and then ... Then the dinosaurs, being social, act out their socialness, and they get together, and they conspire. And, of course, that's what makes Steven Spielberg's movie -- conspiring dinosaurs chasing people around.

So I assume everybody knows that if you actually had a piece of amber and it had an insect in it, and you drilled into it, and you got something out of that insect, and you cloned it, and you did it over and over and over again, you'd have a room full of mosquitos. (Laughter) (Applause) And probably a whole bunch of trees as well.

Now if you want dinosaur DNA, I say go to the dinosaur. So that's what we've done. Back in 1993 when the movie came out, we actually had a grant from the National Science Foundation to attempt to extract DNA from a dinosaur, and we chose the dinosaur on the left, a Tyrannosaurus rex, which was a very nice specimen. And one of my former doctoral students, Dr. Mary Schweitzer, actually had the background to do this sort of thing. And so she looked into the bone of this T. rex, one of the thigh bones, and she actually found some very interesting structures in there. They found these red circular-looking objects, and they looked, for all the world, like red blood cells. And they're in what appear to be the blood channels that go through the bone. And so she thought, well, what the heck. So she sampled some material out of it. Now it wasn't DNA; she didn't find DNA. But she did find heme, which is the biological foundation of hemoglobin. And that was really cool. That was interesting. That was -- here we have 65-million-year-old heme. Well we tried and tried and we couldn't really get anything else out of it.

So a few years went by, and then we started the Hell Creek Project. And the Hell Creek Project was this massive undertaking to get as many dinosaurs as we could possibly find, and hopefully find some dinosaurs that had more material in them. And out in eastern Montana there's a lot of space, a lot of badlands, and not very many people, and so you can go out there and find a lot of stuff. And we did find a lot of stuff. We found a lot of Tyrannosaurs, but we found one special Tyrannosaur, and we called it B-rex. And B-rex was found under a thousand cubic yards of rock. It wasn't a very complete T. rex, and it wasn't a very big T. rex, but it was a very special B-rex. And I and my colleagues cut into it, and we were able to determine, by looking at lines of arrested growth, some lines in it, that B-rex had died at the age of 16. We don't really know how long dinosaurs lived, because we haven't found the oldest one yet. But this one died at the age of 16.

We gave samples to Mary Schweitzer, and she was actually able to determine that B-rex was a female based on medullary tissue found on the inside of the bone. Medullary tissue is the calcium build-up, the calcium storage basically, when an animal is pregnant, when a bird is pregnant. So here was the character that linked birds and dinosaurs. But Mary went further. She took the bone, and she dumped it into acid. Now we all know that bones are fossilized, and so if you dump it into acid, there shouldn't be anything left. But there was something left. There were blood vessels left. There were flexible, clear blood vessels. And so here was the first soft tissue from a dinosaur. It was extraordinary. But she also found osteocytes, which are the cells that laid down the bones. And try and try, we could not find DNA, but she did find evidence of proteins.

But we thought maybe -- well, we thought maybe that the material was breaking down after it was coming out of the ground. We thought maybe it was deteriorating very fast. And so we built a laboratory in the back of an 18-wheeler trailer, and actually took the laboratory to the field where we could get better samples. And we did. We got better material. The cells looked better. The vessels looked better. Found the protein collagen. I mean, it was wonderful stuff. But it's not dinosaur DNA. So we have discovered that dinosaur DNA, and all DNA, just breaks down too fast. We're just not going to be able to do what they did in "Jurassic Park." We're not going to be able to make a dinosaur based on a dinosaur.

But birds are dinosaurs. Birds are living dinosaurs. We actually classify them as dinosaurs. We now call them non-avian dinosaurs and avian dinosaurs. So the non-avian dinosaurs are the big clunky ones that went extinct. Avian dinosaurs are our modern birds. So we don't have to make a dinosaur because we already have them.

(Laughter)

I know, you're as bad as the sixth-graders. (Laughter) The sixth-graders look at it and they say, "No." (Laughter) "You can call it a dinosaur, but look at the velociraptor: the velociraptor is cool." (Laughter) "The chicken is not." (Laughter) So this is our problem, as you can imagine. The chicken is a dinosaur. I mean it really is. You can't argue with it because we're the classifiers and we've classified it that way. (Laughter) (Applause) But the sixth-graders demand it. "Fix the chicken." (Laughter) So that's what I'm here to tell you about: how we are going to fix a chicken.

So we have a number of ways that we actually can fix the chicken. Because evolution works, we actually have some evolutionary tools. We'll call them biological modification tools. We have selection. And we know selection works. We started out with a wolf-like creature and we ended up with a Maltese. I mean, that's -- that's definitely genetic modification. Or any of the other funny-looking little dogs. We also have transgenesis. Transgenesis is really cool too. That's where you take a gene out of one animal and stick it in another one. That's how people make GloFish. You take a glow gene out of a coral or a jellyfish and you stick it in a zebrafish, and, puff, they glow. And that's pretty cool. And they obviously make a lot of money off of them. And now they're making Glow-rabbits and Glow-all-sorts-of-things. I guess we could make a glow chicken. (Laughter) But I don't think that'll satisfy the sixth-graders either.

But there's another thing. There's what we call atavism activation. And atavism activation is basically -- an atavism is an ancestral characteristic. You heard that occasionally children are born with tails, and it's because it's an ancestral characteristic. And so there are a number of atavisms that can happen. Snakes are occasionally born with legs. And here's an example. This is a chicken with teeth. A fellow by the name of Matthew Harris at the University of Wisconsin in Madison actually figured out a way to stimulate the gene for teeth, and so was able to actually turn the tooth gene on and produce teeth in chickens. Now that's a good characteristic. We can save that one. We know we can use that. We can make a chicken with teeth. That's getting closer. That's better than a glowing chicken.

(Laughter)

A friend of mine, a colleague of mine, Dr. Hans Larsson at McGill University, is actually looking at atavisms. And he's looking at them by looking at the embryo genesis of birds and actually looking at how they develop, and he's interested in how birds actually lost their tail. He's also interested in the transformation of the arm, the hand, to the wing. He's looking for those genes as well. And I said, "Well, if you can find those, I can just reverse them and make what I need to make for the sixth-graders." And so he agreed. And so that's what we're looking into.

If you look at dinosaur hands, a velociraptor has that cool-looking hand with the claws on it. Archaeopteryx, which is a bird, a primitive bird, still has that very primitive hand. But as you can see, the pigeon, or a chicken or anything else, another bird, has kind of a weird-looking hand, because the hand is a wing. But the cool thing is that, if you look in the embryo, as the embryo is developing the hand actually looks pretty much like the archaeopteryx hand. It has the three fingers, the three digits. But a gene turns on that actually fuses those together. And so what we're looking for is that gene. We want to stop that gene from turning on, fusing those hands together, so we can get a chicken that hatches out with a three-fingered hand, like the archaeopteryx. And the same goes for the tails. Birds have basically rudimentary tails. And so we know that in embryo, as the animal is developing, it actually has a relatively long tail. But a gene turns on and resorbs the tail, gets rid of it. So that's the other gene we're looking for. We want to stop that tail from resorbing.

So what we're trying to do really is take our chicken, modify it and make the chickenosaurus. (Laughter) It's a cooler-looking chicken. But it's just the very basics. So that really is what we're doing. And people always say, "Why do that? Why make this thing? What good is it?" Well, that's a good question. Actually, I think it's a great way to teach kids about evolutionary biology and developmental biology and all sorts of things. And quite frankly, I think if Colonel Sanders was to be careful how he worded it, he could actually advertise an extra piece. (Laughter)

Anyway -- When our dino-chicken hatches, it will be, obviously, the poster child, or what you might call a poster chick, for technology, entertainment and design.

Thank you.

(Applause)