Cloe Shasha: So welcome, Ibram, and thank you so much for joining us.

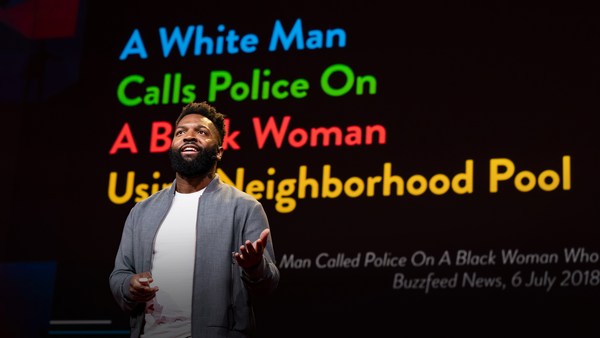

Ibram X. Kendi: Well, thank you, Cloe, and Whitney, and thank you everyone for joining this conversation. And so, a few weeks ago, on the same day we learned about the brutal murder of George Floyd, we also learned that a white woman in Central Park who chose not to leash her dog and was told by a black man nearby that she needed to leash her dog, instead decided to threaten this black male, instead decided to call the police and claim that her life was being threatened. And of course, when we learned about that through a video, many Americans were outraged, and this woman, Amy Cooper, ended up going on national TV and saying, like countless other Americans have said right after they engaged in a racist act, "I am not racist." And I say countless Americans, because when you really think about the history of Americans expressing racist ideas, supporting racist policies, you're really talking about a history of people who have claimed they're not racist, because everyone claims that they're not racist, whether we're talking about the Amy Coopers of the world, whether we're talking about Donald Trump, who, right after he said that majority-black Baltimore is a rat and rodent-infested mess that no human being would want to live in, and he was challenged as being racist, he said, "Actually, I'm the least racist person anywhere in the world." And so really the heartbeat of racism itself has always been denial, and the sound of that heartbeat has always been, "I'm not racist."

And so what I'm trying to do with my work is to really get Americans to eliminate the concept of "not racist" from their vocabulary, and realize we're either being racist or anti-racist. We're either expressing ideas that suggest certain racial groups are better or worse than others, superior or inferior than others. We're either being racist, or we're being anti-racist. We're expressing notions that the racial groups are equals, despite any cultural or even ethnic differences. We're either supporting policies that are leading to racial inequities and injustice, like we saw in Louisville, where Breonna Taylor was murdered, or we're supporting policies and pushing policies that are leading to justice and equity for all.

And so I think we should be very clear about whether we're expressing racist ideas, about whether we're supporting racist policies, and admit when we are, because to be anti-racist is to admit when we expressed a racist idea, is to say, "You know what? When I was doing that in Central Park, I was indeed being racist. But I'm going to change. I'm going to strive to be anti-racist." And to be racist is to constantly deny the racial inequities that pervade American society, to constantly deny the racist ideas that pervade American minds. And so I want to built a just and equitable society, and the only way we're going to even begin that process is if we admit our racism and start building an anti-racist world. Thank you.

CS: Thank you so much for that. You know, your book, "How to Be an Antiracist," has become a bestseller in light of what's been happening, and you've been speaking a bit to the ways in which anti-racism and racism are the only two polar opposite ways to hold a view on racism. I'm curious if you could talk a little bit more about what the basic tenets of anti-racism are, for people who aren't as familiar with it in terms of how they can be anti-racist.

IXK: Sure. And so I mentioned in my talk that the heartbeat of racism is denial, and really the heartbeat of anti-racism is confession, is the recognition that to grow up in this society is to literally at some point in our lives probably internalize ideas that are racist, ideas that suggest certain racial groups are better or worse than others, and because we believe in racial hierarchy, because Americans have been systematically taught that black people are more dangerous, that black people are more criminal-like, when we live in a society where black people are 40 percent of the national incarcerated population, that's going to seem normal to people. When we live in a society in a city like Minneapolis where black people are 20 percent of the population but more than 60 percent of the people being subjected to police shootings, it's going to seem normal. And so to be anti-racist is to believe that there's nothing wrong or inferior about black people or any other racial group. There's nothing dangerous about black people or any other racial group. And so when we see these racial disparities all around us, we see them as abnormal, and then we start to figure out, OK, what policies are behind so many black people being killed by police? What policies are behind so many Latinx people being disproportionately infected with COVID? How can I be a part of the struggle to upend those policies and replace them with more antiracist policies?

Whitney Pennington Rodgers: And so it sounds like you do make that distinction, then, between not racist and anti-racist. I guess, could you talk a little bit more about that and break that down? What is the difference between the two?

IXK: In the most simplest way, a not racist is a racist who is in denial, and an anti-racist is someone who is willing to admit the times in which they are being racist, and who is willing to recognize the inequities and the racial problems of our society, and who is willing to challenge those racial inequities by challenging policy. And so I'm saying this because literally slaveholders, slave traders, imagined that their ideas in our terms were not racist. They would say things like, "Black people are the cursed descendants of Ham, and they're cursed forever into enslavement." This isn't, "I'm not racist." This is, "God's law." They would say things, like, you know, "Based on science, based on ethnology, based on natural history, black people by nature are predisposed to slavery and servility. This is nature's law. I'm not racist. I'm actually doing what nature said I'm supposed to be doing." And so this construct of being not racist and denying one's racism goes all the way back to the origins of this country.

CS: Yeah. And why do you think it has been so hard for some people now to still accept that neutrality is not enough when it comes to racism?

IXK: I think because it takes a lot of work to be anti-racist. You have to be very vulnerable, right? You have to be willing to admit that you were wrong. You have to be willing to admit that if you have more, if you're white, for instance, and you have more, it may not be because you are more. You have to admit that, yeah, you've worked hard potentially, in your life, but you've also had certain advantages which provided you with opportunities that other people did not have. You have to admit those things, and it's very difficult for people to be publicly, and even privately, self-critical.

I think it's also the case of, and I should have probably led with this, how people define "racist." And so people tend to define "racist" as, like, a fixed category, as an identity. This is essential to who a person is. Someone becomes a racist. And so therefore -- And then they also connect a racist with a bad, evil person. They connect a racist with a Ku Klux Klansman or woman. And they're like, "I'm not in the Ku Klux Klan, I'm not a bad person and I've done good things in my life. I've done good things to people of color. And so therefore I can't be racist. I'm not that. That's not my identity. But that's actually not how we should be defining racist. Racist is a descriptive term. It describes what a person is saying or doing in any given moment, and so when a person in one moment is expressing a racist idea, in that moment they are being racist when they're saying black people are lazy. If in the very next moment they're appreciating the cultures of native people, they're being anti-racist.

WPR: And we're going to get to some questions from our community in a moment, but I think when a lot of people hear this idea that you're putting forward, this idea of anti-racism, there's this feeling that this is something that only concerns the white community. And so could you speak a little bit to how the black community and nonwhite, other ethnic minorities can participate in and think about this idea of anti-racism?

IXK: Sure. So if white Americans commonly say, "I'm not racist," people of color commonly say, "I can't be racist, because I'm a person of color." And then some people of color say they can't be racist because they have no power. And so, first and foremost, what I've tried to do in my work is to push back against this idea that people of color have no power. There's nothing more disempowering to say, or to think, as a person of color, than to say you have no power. People of color have long utilized the most basic power that every human being has, and that's the power to resist policy -- that's the power to resist racist policies, that's the power to resist a racist society. But if you're a person of color, and you believe that people coming here from Honduras and El Salvador are invading this country, you believe that these Latinx immigrants are animals and rapists, then you're certainly not, if you're black or Asian or native, going to be a part of the struggle to defend Latinx immigrants, to recognize that Latinx immigrants have as much to give to this country as any other group of people, you're going to view these people as "taking away your jobs," and so therefore you're going to support racist rhetoric, you're going to support racist policies, and even though that is probably going to be harming you, in other words, it's going to be harming, if you're black, immigrants coming from Haiti and Nigeria, if you're Asian, immigrants coming from India. So I think it's critically important for even people of color to realize they have the power to resist, and when people of color view other people of color as the problem, they're not going to view racism as the problem. And anyone who is not viewing racism as the problem is not being anti-racist.

CS: You touched on this a bit in your beginning talk here, but you've talked about how racism is the reason that black communities and communities of color are systematically disadvantaged in America, which has led to so many more deaths from COVID-19 in those communities. And yet the media is often placing the blame on people of color for their vulnerability to illness. So I'm curious, in line with that, what is the relationship between anti-racism and the potential for systemic change?

IXK: I think it's a direct relationship, because when you are -- when you believe and have consumed racist ideas, you're not going to even believe change is necessary because you're going to believe that racial inequality is normal. Or, you're not going to believe change is possible. In other words, you're going to believe that the reason why black people are being killed by police at such high rates or the reason why Latinx people are being infected at such high rates is because there's something wrong with them, and nothing can be changed. And so you wouldn't even begin to even see the need for systemic structural change, let alone be a part of the struggle for systemic structural change. And so, to be anti-racist, again, is to recognize that there's only two causes of racial inequity: either there's something wrong with people, or there's something wrong with power and policy. And if you realize that there's nothing wrong with any group of people, and I keep mentioning groups -- I'm not saying individuals. There's certainly black individuals who didn't take coronavirus seriously, which is one of the reasons why they were infected. But there are white people who didn't take coronavirus seriously. No one has ever proven, actually studies have shown that black people were more likely to take the coronavirus seriously than white people. We're not talking about individuals here, and we certainly should not be individualizing groups. We certainly should not be looking at the individual behavior of one Latinx person or one black person, and saying they're representatives of the group. That's a racist idea in and of itself. And so I'm talking about groups, and if you believe that groups are equals, then the only other alternative, the only other explanation to persisting inequity and injustice, is power and policy. And to then spend your time transforming and challenging power and policy is to spend your time being anti-racist.

WPR: So we have some questions that are coming in from the audience. First one here is from a community member that asks, "When we talk about white privilege, we talk also about the privilege not to have the difficult conversations. Do you feel that's starting to change?"

IXK: I hope so, because I think that white Americans, too, need to simultaneously recognize their privileges, the privileges that they have accrued as a result of their whiteness, and the only way in which they're going to be able to do that is by initiating and having these conversations. But then they also should recognize that, yes, they have more, white Americans have more, due to racist policy, but the question I think white Americans should be having, particularly when they're having these conversations among themselves, is, if we had a more equitable society, would we have more? Because what I'm asking is that, you know, white Americans have more because of racism, but there are other groups of people in other Western democracies who have more than white Americans, and then you start to ask the question, why is it that people in other countries have free health care? Why is it that they have paid family leave? Why is it that they have a massive safety net? Why is it that we do not? And one of the major answers to why we do not here have is racism. One of the major answers as to why Donald Trump is President of the United States is racism. And so I'm not really asking white Americans to be altruistic in order to be anti-racist. We're really asking people to have intelligent self-interest.

Those four million, I should say five million poor whites in 1860 whose poverty was the direct result of the riches of a few thousand white slaveholding families, in order to challenge slavery, we weren't saying, you know, we need you to be altruistic. No, we actually need you to do what's in your self-interest. Those tens of millions of Americans, white Americans, who have lost their jobs as a result of this pandemic, we're not asking them to be altruistic. We're asking them to realize that if we had a different type of government with a different set of priorities, then they would be much better off right now. I'm sorry, don't get me started.

CS: No, we're grateful to you. Thank you. And in line with that, obviously these protests and this movement have led to some progress: the removal of Confederate monuments, the Minneapolis City Council pledging to dismantle the police department, etc. But what do you view as the greatest priority on a policy level as this fight for justice continues? Are there any ways in which we could learn from other countries?

IXK: I don't actually think necessarily there's a singular policy priority. I mean, if someone was to force me to answer, I would probably say two, and that is, high quality free health care for all, and when I say high quality, I'm not just talking about Medicare For All, I'm talking about a simultaneous scenario in which in rural southwest Georgia, where the people are predominantly black and have some of the highest death rates in the country, those counties in southwest Georgia, from COVID, that they would have access to health care as high quality as people do in Atlanta and New York City, and then, simultaneously, that that health care would be free. So many Americans not only of course are dying this year of COVID but also of heart disease and cancer, which are the number one killers before COVID of Americans, and they're disproportionately black.

And so I would say that, and then secondarily, I would say reparations. And many Americans claim that they believe in racial equality, they want to bring about racial equality. Many Americans recognize just how critical economic livelihood is for every person in this country, in this economic system. But then many Americans reject or are not supportive of reparations. And so we have a situation in which white Americans are, last I checked, their median wealth is 10 times the median wealth of black Americans, and according to a recent study, by 2053 -- between now, I should say, and 2053, white median wealth is projected to grow, and this was before this current recession, and black median wealth is expected to redline at zero dollars, and that, based on this current recession, that may be pushed up a decade. And so we not only have a racial wealth gap, but we have a racial wealth gap that's growing.

And so for those Americans who claim they are committed to racial equality who also recognize the importance of economic livelihood and who also know that wealth is inherited, and the majority of wealth is inherited, and when you think of the inheritance, you're thinking of past, and the past policies that many Americans consider to be racist, whether it's slavery or even redlining, how would we even begin to close this growing racial wealth gap without a massive program like reparations?

WPR: Well, sort of connected to this idea of thinking about wealth disparity and wealth inequality in this country, we have a question from community member Dana Perls. She asks, "How do you suggest liberal white organizations effectively address problems of racism within the work environment, particularly in environments where people remain silent in the face of racism or make token statements without looking internally?"

IXK: Sure. And so I would make a few suggestions. One, for several decades now, every workplace has publicly pledged a commitment to diversity. Typically, they have diversity statements. I would basically rip up those diversity statements and write a new statement, and that's a statement committed to anti-racism. And in that statement you would clearly define what a racist idea is, what an anti-racist idea is, what a racist policy is and what an anti-racist policy is. And you would state as a workplace that you're committed to having a culture of anti-racist ideas and having an institution made up of anti-racist policies. And so then everybody can measure everyone's ideas and the policies of that workplace based on that document. And I think that that could begin the process of transformation. I also think it's critically important for workplaces to not only diversify their staff but diversify their upper administration. And I think that's absolutely critical as well.

CS: We have some more questions coming in from the audience. We have one from Melissa Mahoney, who is asking, "Donald Trump seems to be making supporting Black Lives Matter a partisan issue, for example making fun of Mitt Romney for participating in a peaceful protest. How do we uncouple this to make it nonpartisan?"

IXK: Well, I mean, I think that to say the lives of black people is a Democratic declaration is simultaneously stating that Republicans do not value black life. If that's essentially what Donald Trump is saying, if he's stating that there's a problem with marching for black lives, then what is the solution? The solution is not marching. What's the other alternative? The other alternative is not marching for black lives. The other alternative is not caring when black people die of police violence or COVID. And so to me, the way in which we make this a nonpartisan issue is to strike back or argue back in that way, and obviously Republicans are going to claim they're not saying that, but it's a very simple thing: either you believe black lives matter or you don't, and if you believe black lives matter because you believe in human rights, then you believe in the human right for black people and all people to live and to not have to fear police violence and not have to fear the state and not have to fear that a peaceful protest is going to be broken up because some politician wants to get a campaign op, then you're going to institute policy that shows it. Or, you're not.

WPR: So I want to ask a question just about how people can think about anti-racism and how they can actually bring this into their lives. I imagine that a lot of folks, they hear this and they're like, oh, you know, I have to be really thoughtful about how my actions and my words are perceived. What is the perceived intention behind what it is that I'm saying, and that that may feel exhausting, and I think that connects even to this idea of policy. And so I'm curious. There is a huge element of thoughtfulness that comes along with this work of being anti-racist. And what is your reaction and response to those who feel concerned about the mental exhaustion from having to constantly think about how your actions may hurt or harm others?

IXK: So I think part of the concern that people have about mental exhaustion is this idea that they don't ever want to make a mistake, and I think to be anti-racist is to make mistakes, and is to recognize when we make a mistake. For us, what's critical is to have those very clear definitions so that we can assess our words, we can assess our deeds, and when we make a mistake, we just own up to it and say, "You know what, that was a racist idea." "You know what, I was supporting a racist policy, but I'm going to change." The other thing I think is important for us to realize is in many ways we are addicted, and when I say we, individuals and certainly this country, is addicted to racism, and that's one of the reasons why for so many people they're just in denial. People usually deny their addictions. But then, once we realize that we have this addiction, everyone who has been addicted, you know, you talk to friends and family members who are overcoming an addiction to substance abuse, they're not going to say that they're just healed, that they don't have to think about this regularly. You know, someone who is overcoming alcoholism is going to say, "You know what, this is a day-by-day process, and I take it day by day and moment by moment, and yes, it's difficult to restrain myself from reverting back to what I'm addicted to, but at the same time it's liberating, it's freeing, because I'm no longer having to wallow in that addiction. And so I think, and I'm no longer having to hurt people due to my addiction." And I think that's critical. We spend too much time thinking about how we feel and less time thinking about how our actions and ideas make others feel. And I think that's one thing that the George Floyd video forced Americans to do was to really see and hear, especially, how someone feels as a result of their racism.

CS: We have another question from the audience. This one is asking about, "Can you speak to the intersectionality between the work of anti-racism, feminism and gay rights? How does the work of anti-racism relate and affect the work of these other human rights issues?"

IXK: Sure. So I define a racist idea as any idea that suggests a racial group is superior or inferior to another racial group in any way. And I use the term racial group as opposed to race because every race is a collection of racialized intersectional groups, and so you have black women and black men and you have black heterosexuals and black queer people, just as you have Latinx women and white women and Asian men, and what's critical for us to understand is there hasn't just been racist ideas that have targeted, let's say, black people. There has been racist ideas that have been developed and have targeted black women, that have targeted black lesbians, that have targeted black transgender women. And oftentimes these racist ideas targeting these intersectional groups are intersecting with other forms of bigotry that is also targeting these groups. To give an example about black women, one of the oldest racist ideas about black women was this idea that they're inferior women or that they're not even women at all, and that they're inferior to white women, who are the pinnacle of womanhood. And that idea has intersected with this sexist idea that suggests that women are weak, that the more weak a person is, a woman is, the more woman she is, and the stronger a woman is, the more masculine she is. These two ideas have intersected to constantly degrade black women as this idea of the strong, black masculine woman who is inferior to the weak, white woman. And so the only way to really understand these constructs of a weak, superfeminine white woman and a strong, hypermasculine black woman is to understand sexist ideas, is to reject sexist ideas, and I'll say very quickly, the same goes for the intersection of racism and homophobia, in which black queer people have been subjected to this idea that they are more hypersexual because there's this idea of queer people as being more hypersexual than heterosexuals. And so black queer people have been tagged as more hypersexual than white queer people and black heterosexuals. And you can't really see that and understand that and reject that if you're not rejecting and understanding and challenging homophobia too.

WPR: And to this point of challenging, we have another question from Maryam Mohit in our community, who asks, "How do you see cancel culture and anti-racism interacting. For example, when someone did something obviously racist in the past and it comes to light?" How do we respond to that?

IXK: Wow. So I think it's very, very complex. I do obviously encourage people to transform themselves, to change, to admit those times in which they were being racist, and so obviously we as a community have to give people that ability to do that. We can't, when someone admits that they were being racist, we can't immediately obviously cancel them. But I also think that there are people who do something so egregious and there are people who are so unwilling to recognize how egregious what they just did is, so in a particular moment, so not just the horrible, vicious act, but then on top of that the refusal to even admit the horrible, vicious act. In that case, I could see how people would literally want to cancel them, and I think that we have to, on the other hand, we have to have some sort of consequence, public consequence, cultural consequence, for people acting in a racist manner, especially in an extremely egregious way. And for many people, they've decided, you know what, I'm just going to cancel folks. And I'm not going to necessarily critique them, but I do think we should try to figure out a way to discern those who are refusing to transform themselves and those who made a mistake and recognized it and truly are committed to transforming themselves.

CS: Yeah, I mean, one of the concerns many activists have been expressing is that the energy behind the Black Lives Matter movement has to stay high for anti-racist change to truly take place. I think that applies to what you just said as well. And I guess I'm curious what your opinion is on when the protests start to wane and people's donation-matching campaigns fade into the background, how can we all ensure that this conversation about anti-racism stays central?

IXK: Sure. So in "How to Be an Antiracist," in one of the final chapters, is this chapter called "Failure." I talked about what I call feelings advocacy, and this is people feeling bad about what's happening, what happened to George Floyd or what happened to Ahmaud Arbery or what happened to Breonna Taylor. They just feel bad about this country and where this country is headed. And so the way they go about feeling better is by coming to a demonstration. The way they go about feeling better is by donating to a particular organization. The way they go about feeling better is reading a book. And so if this is what many Americans are doing, then once they feel better, in other words once the individual feels better through their participation in book clubs or demonstrations or donation campaigns, then nothing is going to change except, what, their own feelings.

And so we need to move past our feelings. And this isn't to say that people shouldn't feel bad, but we should use our feelings, how horrible we feel about what is going on, to put into place, put into practice, anti-racist power and policies. In other words, our feelings should be driving us. They shouldn't be the end all. This should not be about making us feel better. This should be about transforming this country, and we need to keep our eyes on transforming this country, because if we don't, then once people feel better after this is all over, then we'll be back to the same situation of being horrified by another video, and then feeling bad, and then the cycle will only continue.

WPR: You know, I think when we think about what sort of changes we can implement and how we could make the system work better, make our governments work better, make our police work better, are there models in other countries where -- obviously the history in the United States is really unique in terms of thinking about race and oppression. But when you look to other nations and other cultures, are there other models that you look at as examples that we could potentially implement here?

IXK: I mean, there are so many. There are countries in which police officers don't wear weapons. There are countries who have more people than the United States but less prisoners. There are countries who try to fight violent crime not with more police and prisons but with more jobs and more opportunities, because they know and see that the communities with the highest levels of violent crime tend to be communities with high levels of poverty and long-term unemployment. I think that -- And then, obviously, other countries provide pretty sizable social safety nets for people such that people are not committing crimes out of poverty, such that people are not committing crimes out of despair. And so I think that it's critically important for us to first and foremost think through, OK, if there's nothing wrong with the people, then how can we go about reducing police violence? How can we go about reducing racial health inequities? What policies can we change? What policies have worked? These are the types of questions we need to be asking, because there's never really been anything wrong with the people.

CS: In your "Atlantic" piece called "Who Gets To Be Afraid in America," you wrote, "What I am, a black male, should not matter. Who I am should matter." And I feel that's kind of what you're saying, that in other places maybe that's more possible, and I'm curious when you imagine a country in which who you are mattered first, what does that look like?

IXK: Well, what it looks like for me as a black American is that people do not view me as dangerous and thereby make my existence dangerous. It allows me to walk around this country and to not believe that people are going to fear me because of the color my skin. It allows me to believe, you know what, I didn't get that job because I could have done better on my interview, not because of the color of my skin. It allows me to -- a country where there's racial equity, a country where there's racial justice, you know, a country where there's shared opportunity, a country where African American culture and Native American culture and the cultures of Mexican Americans and Korean Americans are all valued equally, that no one is being asked to assimilate into white American culture. There's no such thing as standard professional wear. There's no such thing as, well, you need to learn how to speak English in order to be an American. And we would truly not only have equity and justice for all but we would somehow have found a way to appreciate difference, to appreciate all of the human ethnic and cultural difference that exists in the United States. This is what could make this country great, in which we literally become a country where you could literally travel around this country and learn about cultures from all over the world and appreciate those cultures, and understand even your own culture from what other people are doing. There's so much beauty here amid all this pain and I just want to peel away and remove away all of those scabs of racist policies so that people can heal and so that we can see true beauty.

WPR: And Ibram, when you think about this moment, where do you see that on the spectrum of progress towards reaching that true beauty?

IXK: Well, I think, for me, I always see progress and resistance in demonstrations and know just because people are calling from town squares and from city halls for progressive, systemic change that that change is here, but people are calling and people are calling in small towns, in big cities, and people are calling from places we've heard of and places we need to have heard of. People are calling for change, and people are fed up. I mean, we're living in a time in which we're facing a viral pandemic, a racial pandemic within that viral pandemic of people of color disproportionately being infected and dying, even an economic pandemic with over 40 million Americans having lost their jobs, and certainly this pandemic of police violence, and then people demonstrating against police violence only to suffer police violence at demonstrations. I mean, people see there's a fundamental problem here, and there's a problem that can be solved. There's an America that can be created, and people are calling for this, and that is always the beginning. The beginning is what we're experiencing now.

CS: I think that this next audience question follows well from that, which is, "What gives you hope right now?"

IXK: So certainly resistance to racism has always given me hope, and so even if, let's say, six months ago we were not in a time in which almost every night all over this country people were demonstrating against racism, but I could just look to history when people were resisting. And so resistance always brings me hope, because it is always resistance, and of course it's stormy, but the rainbow is typically on the other side. But I also receive hope philosophically, because I know that in order to bring about change, we have to believe in change. There's just no way a change maker can be cynical. It's impossible. So I know I have to believe in change in order to bring it about.

WPR: And we have another question here which addresses some of the things you talked about before in terms of the structural change that we need to bring about. From Maryam Mohit: "In terms of putting into practice the transformative policies, is then the most important thing to loudly vote the right people into office at every level who can make those structural changes happen?"

IXK: So I think that that is part of it. I certainly think we should vote into office people who, from school boards to the President of the United States, people who are committed to instituting anti-racist policies that lead to equity and justice, and I think that that's critically important, but I don't think that we should think that that's the only thing we should be focused on or the only thing that we should be doing. And there are institutions, there are neighborhoods that need to be transformed, that are to a certain extent outside of the purview of a policymaker who is an elected official. There are administrators and CEOs and presidents who have the power to transform policies within their spheres, within their institutions, and so we should be focused there. The last thing I'll say about voting is, I wrote a series of pieces for "The Atlantic" early this year that sought to get Americans thinking about who I call "the other swing voter," and not the traditional swing voter who swings from Republican to Democrat who are primarily older and white. I'm talking about the people who swing from voting Democrat to not voting at all. And these people are typically younger and they're typically people of color, but they're especially young people of color, especially young black and Latinx Americans. And so we should view these people, these young, black and Latino voters who are trying to decide whether to vote as swing voters in the way we view these people who are trying to decide between whether to vote for, let's say, Trump or Biden in the general election. In other words, to view them both as swing voters is to view them both in a way that, OK, we need to persuade these people. They're not political cattle. We're not just going to turn them out. We need to encourage and persuade them, and then we also for these other swing voters need to make it easier for them to vote, and typically these young people of color, it's the hardest for them to vote because of voter suppression policies.

CS: Thank you, Ibram. Well, we're going to come to a close of this interview, but I would love to ask you to read something that you wrote a couple of days ago on Instagram. You wrote this beautiful caption on a photo of your daughter, and I'm wondering if you'd be willing to share that with us and briefly tell us how we could each take this perspective into our own lives.

IXK: Sure, so yeah, I posted a picture of my four-year-old daughter Imani, and in the caption I wrote, "I love, and because I love, I resist. There have been many theories on what's fueling the growing demonstrations against racism in public and private. Let me offer another one: love. We love. We know the lives of our loved ones, especially our black loved ones, are in danger under the violence of racism. People ask me all the time what fuels me. It is the same: love, love of this little girl, love of all the little and big people who I want to live full lives in the fullness of their humanity, not barred by racist policies, not degraded by racist ideas, not terrorized by racist violence. Let us be anti-racist. Let us defend life. Let us defend our human rights to live and live fully, because we love." And, you know, Cloe, I just wanted to sort of emphasize that at the heart of being anti-racist is love, is loving one's country, loving one's humanity, loving one's relatives and family and friends, and certainly loving oneself. And I consider love to be a verb. I consider love to be, I'm helping another, and even myself, to constantly grow into a better form of myself, of themselves, that they've expressed who they want to be. And so to love this country and to love humanity is to push humanity constructively to be a better form of itself, and there's no way we're going to be a better form, there's no way we can build a better humanity, while we still have on the shackles of racism.

WPR: I think that's so beautiful. I appreciate everything you've shared, Ibram. I feel like it's made it really clear this is not an easy fix. Right? There is no band-aid option here that will make this go away, that this takes work from all of us, and I really appreciate all of the honesty and thoughtfulness that you've brought to this today.

IXK: You're welcome. Thank you so much for having this conversation with me.

CS: Thank you so much, Ibram. We're really grateful to you for joining us.

IXK: Thank you.