Poverty is really linked to so many things in life. Because it is not just an economic phenomenon. It’s not just a social phenomenon. It's an individual and a family. It's at the base of really what it means to be human and how we think about human rights.

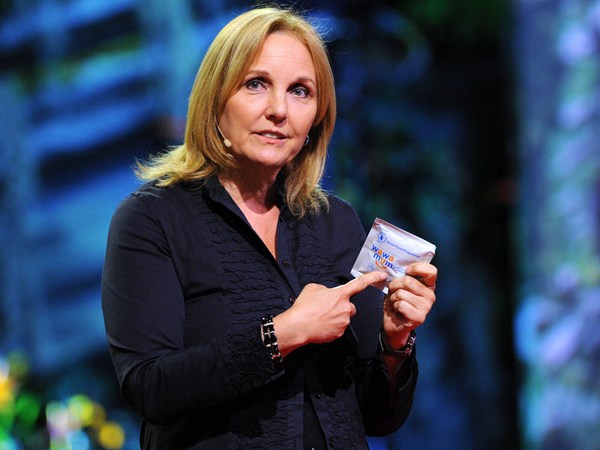

My name is Huiyi Lin. I'm an artist with Chow and Lin. I've been creating a project called "The Poverty Line" for the past 14 years with my partner, Stefen Chow. I calculated the per-person per-day rate of the national poverty line in China. We then went to the local markets to purchase food items with that amount of money. Stefen photographed the food on local newspapers, showing what poverty looks like on a plate.

The poverty line tries to understand and look at a very simple question: what does it mean to be poor? We're looking at it from the angle of food choices, which would be available for somebody living at the poverty line of a country. When we talk about choices, we also need to understand the scope in which we are able to make choices. And that really changes the way that we can behave, the way that we relate to each other, the way that we see each other and the way that we can work together.

When we first created the project, we didn't even know what it was. It was kind of just a way of communicating between the two of us, a way of extending that discussion about what poverty means. But when we started releasing the photographs online and we saw reactions coming from people in the US, from people in Europe and people in Russia, and then later on, only much later on, people in China themselves, whether it was right, whether it was too little, whether it looks good, whether it looks fresh, whether it wasn't as what they expected.

We found that different people have different responses to the same set of photographs. And it was very strange. It was really unexpected. There is no policy report I could have ever written that would have generated this kind of response.

For me, that was supposed to be a very objective way of looking at poverty, but yet it became very subjective in the way that people connected and felt emotional or very deeply personal about the food that we were presenting. We all have reactions, basically to food, because it is a daily unifying human ritual. That kind of very visceral, instinctive reaction was something that surprised me, but later on became a very meaningful part of how the work engages people.

So we expanded the concept to different places. We photographed what daily food choices at the poverty line looks like all over the world, and we ultimately covered 38 countries and territories across six continents.

Poverty is at the base of many issues that we see today, and it will also be affected by many of the trends that we see in climate change, in conflict, in migration, and many crises, whether man-made or natural. Our photographs don't change that, but they do prompt conversations.

"The Poverty Line" images have sparked policy conversations and prompted new research. Working in policy or working in economic frameworks, there is a tendency to look at the broad strokes, at the macro view, but it really depends on what is the local context, and it's not something in the hands of somebody else. It really is, you know, the next person beside us, the people in our own communities. We need to understand that we are all part of the same system and we all play a role in it.

"The Poverty Line" is really about bridging the gaps in our understanding, making us very curious, also motivated to want to understand more. Because there are so many things which really bind us together, and that really changes how we view the world, how we view decision making, and how we view the people around us.