In 2014, I met Sudan. The last male white northern rhino in the world. Just four years later, Sudan died. Leaving two, both female, northern white rhinos alive. The species are effectively extinct. And they're not the only ones. We’re losing biodiversity at an unprecedented scale. We’re in the middle of what is termed the sixth mass extinction, a biodiversity crisis. And we don’t even have the scientific and technological solution to keep up knowing what we’re losing and how fast. The International Union for Conservation of Nature Red List is the official international organization that keeps track of the biodiversity of the world, and of the 130 000 species that they track out of the millions that are out there. Majority have their conservation status as data deficient or their population trend as unknown. And these are iconic species like killer whales and polar bears. We don’t know how well they’re doing. We can’t make policy decisions. We can’t put the right resources to protect them. How many African elephants are there and how fast are they lost to poaching? How far do the whales go and how many juvenile turtles survive to adulthood? We don't know. And these data are critical to conservation decisions. So how do we get those data? There are not enough scientists to track every animal everywhere all over the world and not enough collars and satellite tags to track them. Besides to put a satellite tag or a collar on an animal, you have to actually capture them, tranquilize them, and have a vet present to monitor the vital signs of that animal. And even if everything goes right, the collar can get snagged on a branch or the satellite tag can get infected. So this can be dangerous to the animals. Today, images are the most abundant readily available source of information about anything. From what you had for lunch to what animals you saw in your backyard or in a safari tour. Coming from scientists, field assistants, camera traps, as well as drones and tourists going on safaris and whale watching tours. There are millions of images out there. If I could only take those millions of images and extract the information about wildlife. Well, artificial intelligence to the rescue. We designed algorithms and created a platform, Wild Book, that uses modern artificial intelligence, machine learning and computer vision to take these millions of images, and find the ones that contain animals. Find where the animals are in those pictures, including that baby elephant hiding behind its mom and figure out not only species but down to individual animals. Recognizing Zippy the zebra and Joe the giraffe and Terry the turtle and Willie the whale, using the unique markings on an animal body like a fingerprint. A body print, if you wish. The stripes, spots, wrinkles, notches, as well as the shape of a whale’s fluke of the dorsal fin of a dolphin. These are unique, as every animal is. And with information on when and where the image was taken, we can now use pictures. Instead of collars and tags to track animals. Count them and even figure out their social network, who is whose animal’s friend. This is an example page from a Wild Book for whales and dolphins, flukebook. And this is Pinchy, the most cited animal in that Wild Book. Pinchy is a celebrity. She’s a ham. She likes getting her picture taken. She has more than 600 sightings around Dominica. She lives there. She hangs out there. And flukebook, the Wild Book for whales and dolphins, contains more than a million images of almost 46 000 identified individuals. Providing the basis for science and conservation. We even developed an artificial intelligence agent, who scours social media, publicly-posted images and videos, and finds the ones that contain animals. Sends them off to this machine learning back engine for identification and adding to the appropriate page the right Wild Book, and then posting back in the comments of the social media saying, “Hey, at 2 minutes 46 seconds, we found this whale shark in your video.” “Here’s everything we know about it.” And people respond, “Wow, this is amazing. How can I help?” That... The “how can I help?” We engage people right were they are. Turning their vacation videos into data for science and conservation with the help of artificial intelligence. The Wild Book for whale sharks contains data now for more than 12 000 individual whale sharks. From photographs brought in by almost 9000 citizen scientists, 200 plus conservation and science projects, and one very intelligent agent from social media that together, that is now the foundation for the IUCN Red List entry, for the species. Providing not only data for the global population size, but determining its conservation status and changing it from vulnerable to endangered. And the population trend from stable to decreasing. Not because the species are doing any worse, but because we now know better. We can make better decisions. We can create better policy. We can put the right resources to support it. We have Wild Books for 53 species from marine to terrestrial, spanning the entire globe and growing. The technology in Wild Book was also used for the first ever full census of the entire species, the endangered grevers zebra. Using photographs from ordinary people. Just taking pictures for two days. For the first time, in January 2016, hundreds of people were driving around Kenya, the country containing 95% of this endangered species. From rangers and school kids to tourists with telephoto cameras, they took more than 40 000 images and the machine learning technology of Wild Book identified all the animals, providing the most accurate count of the species. So much so that Kenya Wildlife Service said that this is how we’re going to track the species from now on and do this every two years with the event known as the Great Grevers Rally. So we repeated it in 2018 with more than 1000 people, and also in 2020. And that data became the basis for the IUCN Red List entry for the Grevy’s Zebra, as well as for the conservation policy, the Endangered Species Management for Kenya Wildlife Service. The associate warden of Kenya Wildlife Service also said this shows the power of citizen science and machine learning for conservation. Artificial intelligence democratizes science, it connects people bringing together the pixels of individual cameras into the global view of biodiversity. A. I. helps create conservation policy science and engage people at large scale and high resolution. And it takes the incredible team of Wild Me, the non-profit home of Wild Book, as well as thousands of people all over the world who take pictures, annotate them and make them ready for A. I., create technology and use it for conservation. As well as all the people who work out there in the field protecting the biodiversity of the planet. And I hope you join us. Thank you.

Related talks

Tom Gruber: How AI can enhance our memory, work and social lives

Max Tegmark: How to get empowered, not overpowered, by AI

Alex Wissner-Gross: A new equation for intelligence

Margaret Mitchell: How we can build AI to help humans, not hurt us

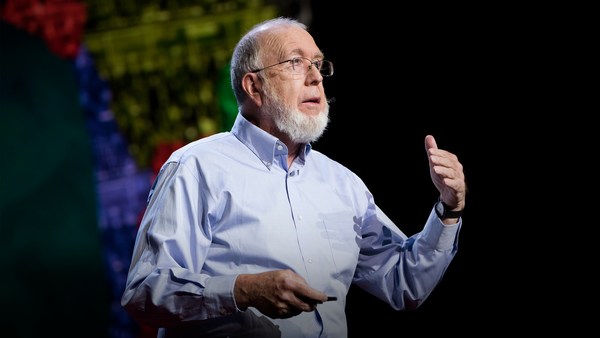

Kevin Kelly: How AI can bring on a second Industrial Revolution