I'm going to talk about your mindset. Does your mindset correspond to my dataset? (Laughter) If not, one or the other needs upgrading, isn't it?

When I talk to my students about global issues, and I listen to them in the coffee break, they always talk about "we" and "them." And when they come back into the lecture room I ask them, "What do you mean with "we" and "them"? "Oh, it's very easy. It's the western world and it's the developing world," they say. "We learned it in college." And what is the definition then? "The definition? Everyone knows," they say.

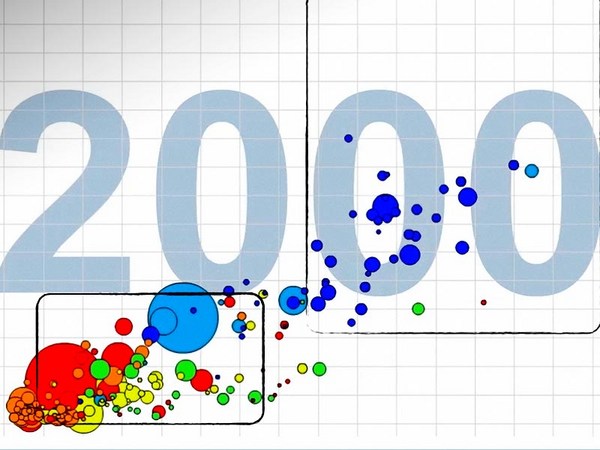

But then you know, I press them like this. So one girl said, very cleverly, "It's very easy. Western world is a long life in a small family. Developing world is a short life in a large family." And I like that definition, because it enabled me to transfer their mindset into the dataset. And here you have the dataset. So, you can see that what we have on this axis here is size of family. One, two, three, four, five children per woman on this axis. And here, length of life, life expectancy, 30, 40, 50. Exactly what the students said was their concept about the world.

And really this is about the bedroom. Whether the man and woman decide to have small family, and take care of their kids, and how long they will live. It's about the bathroom and the kitchen. If you have soap, water and food, you know, you can live long. And the students were right. It wasn't that the world consisted -- the world consisted here, of one set of countries over here, which had large families and short life. Developing world. And we had one set of countries up there which was the western world. They had small families and long life.

And you are going to see here the amazing thing that has happened in the world during my lifetime. Then the developing countries applied soap and water, vaccination. And all the developing world started to apply family planning. And partly to USA who help to provide technical advice and investment. And you see all the world moves over to a two child family, and a life with 60 to 70 years.

But some countries remain back in this area here. And you can see we still have Afghanistan down here. We have Liberia. We have Congo. So we have countries living there. So the problem I had is that the worldview that my students had corresponds to reality in the world the year their teachers were born. (Laughter) (Applause)

And we, in fact, when we have played this over the world. I was at the Global Health Conference here in Washington last week, and I could see the wrong concept even active people in United States had, that they didn't realize the improvement of Mexico there, and China, in relation to United States. Look here when I move them forward. Here we go. They catch up. There's Mexico. It's on par with United States in these two social dimensions. There was less than five percent of the specialists in Global Health that was aware of this. This great nation, Mexico, has the problem that arms are coming from North, across the borders, so they had to stop that, because they have this strange relationship to the United States, you know.

But if I would change this axis here, I would instead put income per person. Income per person. I can put that here. And we will then see a completely different picture. By the way, I'm teaching you how to use our website, Gapminder World, while I'm correcting this, because this is a free utility on the net. And when I now finally got it right, I can go back 200 years in history. And I can find United States up there. And I can let the other countries be shown. And now I have income per person on this axis. And United States only had some, one, two thousand dollars at that time. And the life expectancy was 35 to 40 years, on par with Afghanistan today.

And what has happened in the world, I will show now. This is instead of studying history for one year at university. You can watch me for one minute now and you'll see the whole thing. (Laughter) You can see how the brown bubbles, which is west Europe, and the yellow one, which is the United States, they get richer and richer and also start to get healthier and healthier. And this is now 100 years ago, where the rest of the world remains behind. Here we come. And that was the influenza. That's why we are so scared about flu, isn't it? It's still remembered. The fall of life expectancy. And then we come up. Not until independence started.

Look here You have China over there, you have India over there, and this is what has happened. Did you note there, that we have Mexico up there? Mexico is not at all on par with the United States, but they are quite close. And especially, it's interesting to see China and the United States during 200 years, because I have my oldest son now working for Google, after Google acquired this software. Because in fact, this is child labor. My son and his wife sat in a closet for many years and developed this. And my youngest son, who studied Chinese in Beijing. So they come in with the two perspectives I have, you know? And my son, youngest son who studied in Beijing, in China, he got a long-term perspective. Whereas when my oldest son, who works for Google, he should develop by quarter, or by half-year. Or Google is quite generous, so he can have one or two years to go.

But in China they look generation after generation because they remember the very embarrassing period, for 100 years, when they went backwards. And then they would remember the first part of last century, which was really bad, and we could go by this so-called Great Leap Forward. But this was 1963. Mao Tse-Tung eventually brought health to China, and then he died, and then Deng Xiaoping started this amazing move forward.

Isn't it strange to see that the United States first grew the economy, and then gradually got rich? Whereas China could get healthy much earlier, because they applied the knowledge of education, nutrition, and then also benefits of penicillin and vaccines and family planning. And Asia could have social development before they got the economic development. So to me, as a public health professor, it's not strange that all these countries grow so fast now.

Because what you see here, what you see here is the flat world of Thomas Friedman, isn't it. It's not really, really flat. But the middle income countries -- and this is where I suggest to my students, stop using the concept "developing world." Because after all, talking about the developing world is like having two chapters in the history of the United States.

The last chapter is about present, and president Obama, and the other is about the past, where you cover everything from Washington to Eisenhower. Because Washington to Eisenhower, that is what we find in the developing world. We could actually go to Mayflower to Eisenhower, and that would be put together into a developing world, which is rightly growing its cities in a very amazing way, which have great entrepreneurs, but also have the collapsing countries.

So, how could we make better sense about this? Well, one way of trying is to see whether we could look at income distribution. This is the income distribution of peoples in the world, from $1. This is where you have food to eat. These people go to bed hungry. And this is the number of people. This is $10, whether you have a public or a private health service system. This is where you can provide health service for your family and school for your children, and this is OECD countries: Green, Latin America, East Europe. This is East Asia, and the light blue there is South Asia.

And this is how the world changed. It changed like this. Can you see how it's growing? And how hundreds of millions and billions is coming out of poverty in Asia? And it goes over here? And I come now, into projections, but I have to stop at the door of Lehman Brothers there, you know, because -- (Laughter) that's where the projections are not valid any longer. Probably the world will do this. and then it will continue forward like this. But more or less, this is what will happen, and we have a world which cannot be looked upon as divided.

We have the high income countries here, with the United States as a leading power; we have the emerging economies in the middle, which provide a lot of the funding for the bailout; and we have the low income countries here. Yeah, this is a fact that from where the money comes, they have been saving, you know, over the last decade. And here we have the low income countries where entrepreneurs are. And here we have the countries in collapse and war, like Afghanistan, Somalia, parts of Congo, Darfur. We have all this at the same time.

That's why it's so problematic to describe what has happened in the developing world. Because it's so different, what has happened there. And that's why I suggest a slightly different approach of what you would call it. And you have huge differences within countries also. I heard that your departments here were by regions. Here you have Sub-Saharan Africa, South Asia, East Asia, Arab states, East Europe, Latin America, and OECD. And on this axis, GDP. And on this, heath, child survival, and it doesn't come as a surprise that Africa south of Sahara is at the bottom.

But when I split it, when I split it into country bubbles, the size of the bubbles here is the population. Then you see Sierra Leone and Mauritius, completely different. There is such a difference within Sub-Saharan Africa. And I can split the others. Here is the South Asian, Arab world. Now all your different departments. East Europe, Latin America, and OECD countries. And here were are. We have a continuum in the world. We cannot put it into two parts.

It is Mayflower down here. It is Washington here, building, building countries. It's Lincoln here, advancing them. It's Eisenhower bringing modernity into the countries. And then it's United States today, up here. And we have countries all this way. Now, this is the important thing of understanding how the world has changed. At this point I decided to make a pause. (Laughter)

And it is my task, on behalf of the rest of the world, to convey a thanks to the U.S. taxpayers, for Demographic Health Survey. Many are not aware of -- no, this is not a joke. This is very serious. It is due to USA's continuous sponsoring during 25 years of the very good methodology for measuring child mortality that we have a grasp of what's happening in the world. (Applause) And it is U.S. government at its best, without advocacy, providing facts, that it's useful for the society. And providing data free of charge on the internet, for the world to use. Thank you very much.

Quite the opposite of the World Bank, who compiled data with government money, tax money, and then they sell it to add a little profit, in a very inefficient, Gutenberg way. (Applause) But the people doing that at the World Bank are among the best in the world. And they are highly skilled professionals. It's just that we would like to upgrade our international agencies to deal with the world in the modern way, as we do. And when it comes to free data and transparency, United States of America is one of the best. And that doesn't come easy from the mouth of a Swedish public health professor. (Laughter) And I'm not paid to come here, no.

I would like to show you what happens with the data, what we can show with this data. Look here. This is the world. With income down there and child mortality. And what has happened in the world? Since 1950, during the last 50 years we have had a fall in child mortality. And it is the DHS that makes it possible to know this. And we had an increase in income. And the blue former developing countries are mixing up with the former industrialized western world. We have a continuum. But we still have, of course, Congo, up there. We still have as poor countries as we have had, always, in history. And that's the bottom billion, where we've heard today about a completely new approach to do it.

And how fast has this happened? Well, MDG 4. The United States has not been so eager to use MDG 4. But you have been the main sponsor that has enabled us to measure it, because it's the only child mortality that we can measure. And we used to say that it should fall four percent per year. Let's see what Sweden has done. We used to boast about fast social progress. That's where we were, 1900. 1900, Sweden was there. Same child mortality as Bangladesh had, 1990, though they had lower income. They started very well. They used the aid well. They vaccinated the kids. They get better water. And they reduced child mortality, with an amazing 4.7 percent per year. They beat Sweden. I run Sweden the same 16 year period.

Second round, it's Sweden, 1916, against Egypt, 1990. Here we go. Once again the USA is part of the reason here. They get safe water, they get food for the poor, and they get malaria eradicated. 5.5 percent. They are faster than the millennium development goal.

And third chance for Sweden, against Brazil here. Brazil here has amazing social improvement over the last 16 years, and they go faster than Sweden. This means that the world is converging. The middle income countries, the emerging economy, they are catching up. They are moving to cities, where they also get better assistance for that.

Well the Swedish students protest at this point. They say, "This is not fair, because these countries had vaccines and antibiotics that were not available for Sweden. We have to do real-time competition." Okay. I give you Singapore, the year I was born. Singapore had twice the child mortality of Sweden. It's the most tropical country in the world, a marshland on the equator. And here we go. It took a little time for them to get independent. But then they started to grow their economy. And they made the social investment. They got away malaria. They got a magnificent health system that beat both the U.S. and Sweden. We never thought it would happen that they would win over Sweden! (Applause)

All these green countries are achieving millennium development goals. These yellow are just about to be doing this. These red are the countries that doesn't do it, and the policy has to be improved. Not simplistic extrapolation. We have to really find a way of supporting those countries in a better way. We have to respect the middle income countries on what they are doing. And we have to fact-base the whole way we look at the world.

This is dollar per person. This is HIV in the countries. The blue is Africa. The size of the bubbles is how many are HIV affected. You see the tragedy in South Africa there. About 20 percent of the adult population are infected. And in spite of them having quite a high income, they have a huge number of HIV infected. But you also see that there are African countries down here. There is no such thing as an HIV epidemic in Africa. There's a number, five to 10 countries in Africa that has the same level as Sweden and United States. And there are others who are extremely high.

And I will show you that what has happened in one of the best countries, with the most vibrant economy in Africa and a good governance, Botswana. They have a very high level. It's coming down. But now it's not falling, because there, with help from PEPFAR, it's working with treatment. And people are not dying. And you can see it's not that easy, that it is war which caused this. Because here, in Congo, there is war. And here, in Zambia, there is peace.

And it's not the economy. Richer country has a little higher. If I split Tanzania in its income, the richer 20 percent in Tanzania has more HIV than the poorest one. And it's really different within each country. Look at the provinces of Kenya. They are very different. And this is the situation you see. It's not deep poverty. It's the special situation, probably of concurrent sexual partnership among part of the heterosexual population in some countries, or some parts of countries, in south and eastern Africa.

Don't make it Africa. Don't make it a race issue. Make it a local issue. And do prevention at each place, in the way it can be done there. So to just end up, there are things of suffering in the one billion poorest, which we don't know. Those who live beyond the cellphone, those who have yet to see a computer, those who have no electricity at home.

This is the disease, Konzo, I spent 20 years elucidating in Africa. It's caused by fast processing of toxic cassava root in famine situation. It's similar to the pellagra epidemic in Mississippi in the '30s. It's similar to other nutritional diseases. It will never affect a rich person.

We have seen it here in Mozambique. This is the epidemic in Mozambique. This is an epidemic in northern Tanzania. You never heard about the disease. But it's much more than Ebola that has been affected by this disease. Cause crippling throughout the world. And over the last two years, 2,000 people has been crippled in the southern tip of Bandundu region. That used to be the illegal diamond trade, from the UNITA-dominated area in Angola. That has now disappeared, and they are now in great economic problem. And one week ago, for the first time, there were four lines on the Internet.

Don't get confused of the progress of the emerging economies and the great capacity of people in the middle income countries and in peaceful low income countries. There is still mystery in one billion. And we have to have more concepts than just developing countries and developing world. We need a new mindset. The world is converging, but -- but -- but not the bottom billion. They are still as poor as they've ever been. It's not sustainable, and it will not happen around one superpower. But you will remain one of the most important superpowers, and the most hopeful superpower, for the time to be. And this institution will have a very crucial role, not for United States, but for the world. So you have a very bad name, State Department. This is not the State Department. It's the World Department. And we have a high hope in you. Thank you very much. (Applause)