I have a doppelganger. (Laughter) Dr. Gero is a brilliant but slightly mad scientist in the "Dragonball Z: Android Saga." If you look very carefully, you see that his skull has been replaced with a transparent Plexiglas dome so that the workings of his brain can be observed and also controlled with light. That's exactly what I do -- optical mind control.

(Laughter)

But in contrast to my evil twin who lusts after world domination, my motives are not sinister. I control the brain in order to understand how it works. Now wait a minute, you may say, how can you go straight to controlling the brain without understanding it first? Isn't that putting the cart before the horse? Many neuroscientists agree with this view and think that understanding will come from more detailed observation and analysis. They say, "If we could record the activity of our neurons, we would understand the brain." But think for a moment what that means. Even if we could measure what every cell is doing at all times, we would still have to make sense of the recorded activity patterns, and that's so difficult, chances are we'll understand these patterns just as little as the brains that produce them.

Take a look at what brain activity might look like. In this simulation, each black dot is one nerve cell. The dot is visible whenever a cell fires an electrical impulse. There's 10,000 neurons here. So you're looking at roughly one percent of the brain of a cockroach. Your brains are about 100 million times more complicated. Somewhere, in a pattern like this, is you, your perceptions, your emotions, your memories, your plans for the future. But we don't know where, since we don't know how to read the pattern. We don't understand the code used by the brain. To make progress, we need to break the code. But how? An experienced code-breaker will tell you that in order to figure out what the symbols in a code mean, it's essential to be able to play with them, to rearrange them at will. So in this situation too, to decode the information contained in patterns like this, watching alone won't do. We need to rearrange the pattern. In other words, instead of recording the activity of neurons, we need to control it. It's not essential that we can control the activity of all neurons in the brain, just some. The more targeted our interventions, the better. And I'll show you in a moment how we can achieve the necessary precision.

And since I'm realistic, rather than grandiose, I don't claim that the ability to control the function of the nervous system will at once unravel all its mysteries. But we'll certainly learn a lot. Now, I'm by no means the first person to realize how powerful a tool intervention is. The history of attempts to tinker with the function of the nervous system is long and illustrious. It dates back at least 200 years, to Galvani's famous experiments in the late 18th century and beyond. Galvani showed that a frog's legs twitched when he connected the lumbar nerve to a source of electrical current. This experiment revealed the first, and perhaps most fundamental, nugget of the neural code: that information is written in the form of electrical impulses. Galvani's approach of probing the nervous system with electrodes has remained state-of-the-art until today, despite a number of drawbacks. Sticking wires into the brain is obviously rather crude. It's hard to do in animals that run around, and there is a physical limit to the number of wires that can be inserted simultaneously.

So around the turn of the last century, I started to think, "Wouldn't it be wonderful if one could take this logic and turn it upside down?" So instead of inserting a wire into one spot of the brain, re-engineer the brain itself so that some of its neural elements become responsive to diffusely broadcast signals such as a flash of light. Such an approach would literally, in a flash of light, overcome many of the obstacles to discovery. First, it's clearly a non-invasive, wireless form of communication. And second, just as in a radio broadcast, you can communicate with many receivers at once. You don't need to know where these receivers are, and it doesn't matter if these receivers move -- just think of the stereo in your car. It gets even better, for it turns out that we can fabricate the receivers out of materials that are encoded in DNA. So each nerve cell with the right genetic makeup will spontaneously produce a receiver that allows us to control its function. I hope you'll appreciate the beautiful simplicity of this concept. There's no high-tech gizmos here, just biology revealed through biology.

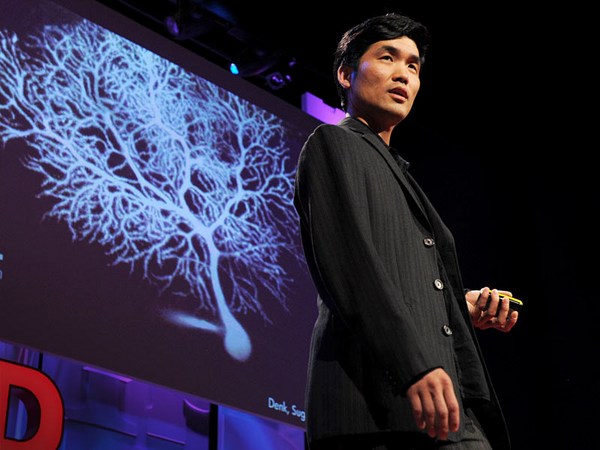

Now let's take a look at these miraculous receivers up close. As we zoom in on one of these purple neurons, we see that its outer membrane is studded with microscopic pores. Pores like these conduct electrical current and are responsible for all the communication in the nervous system. But these pores here are special. They are coupled to light receptors similar to the ones in your eyes. Whenever a flash of light hits the receptor, the pore opens, an electrical current is switched on, and the neuron fires electrical impulses. Because the light-activated pore is encoded in DNA, we can achieve incredible precision. This is because, although each cell in our bodies contains the same set of genes, different mixes of genes get turned on and off in different cells. You can exploit this to make sure that only some neurons contain our light-activated pore and others don't. So in this cartoon, the bluish white cell in the upper-left corner does not respond to light because it lacks the light-activated pore. The approach works so well that we can write purely artificial messages directly to the brain. In this example, each electrical impulse, each deflection on the trace, is caused by a brief pulse of light. And the approach, of course, also works in moving, behaving animals.

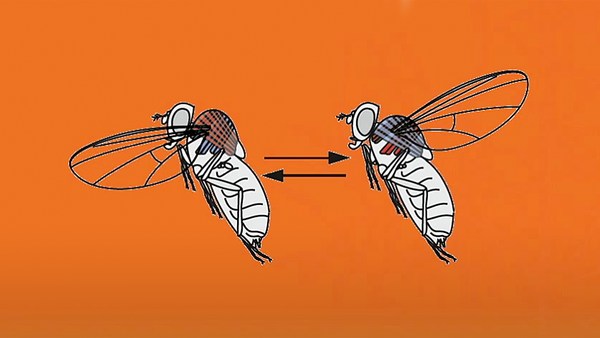

This is the first ever such experiment, sort of the optical equivalent of Galvani's. It was done six or seven years ago by my then graduate student, Susana Lima. Susana had engineered the fruit fly on the left so that just two out of the 200,000 cells in its brain expressed the light-activated pore. You're familiar with these cells because they are the ones that frustrate you when you try to swat the fly. They trained the escape reflex that makes the fly jump into the air and fly away whenever you move your hand in position. And you can see here that the flash of light has exactly the same effect. The animal jumps, it spreads its wings, it vibrates them, but it can't actually take off because the fly is sandwiched between two glass plates. Now to make sure that this was no reaction of the fly to a flash it could see, Susana did a simple but brutally effective experiment. She cut the heads off of her flies. These headless bodies can live for about a day, but they don't do much. They just stand around and groom excessively. So it seems that the only trait that survives decapitation is vanity. (Laughter) Anyway, as you'll see in a moment, Susana was able to turn on the flight motor of what's the equivalent of the spinal cord of these flies and get some of the headless bodies to actually take off and fly away. They didn't get very far, obviously. Since we took these first steps, the field of optogenetics has exploded. And there are now hundreds of labs using these approaches.

And we've come a long way since Galvani's and Susana's first successes in making animals twitch or jump. We can now actually interfere with their psychology in rather profound ways, as I'll show you in my last example, which is directed at a familiar question. Life is a string of choices creating a constant pressure to decide what to do next. We cope with this pressure by having brains, and within our brains, decision-making centers that I've called here the "Actor." The Actor implements a policy that takes into account the state of the environment and the context in which we operate. Our actions change the environment, or context, and these changes are then fed back into the decision loop.

Now to put some neurobiological meat on this abstract model, we constructed a simple one-dimensional world for our favorite subject, fruit flies. Each chamber in these two vertical stacks contains one fly. The left and the right halves of the chamber are filled with two different odors, and a security camera watches as the flies pace up and down between them. Here's some such CCTV footage. Whenever a fly reaches the midpoint of the chamber where the two odor streams meet, it has to make a decision. It has to decide whether to turn around and stay in the same odor, or whether to cross the midline and try something new. These decisions are clearly a reflection of the Actor's policy. Now for an intelligent being like our fly, this policy is not written in stone but rather changes as the animal learns from experience. We can incorporate such an element of adaptive intelligence into our model by assuming that the fly's brain contains not only an Actor, but a different group of cells, a "Critic," that provides a running commentary on the Actor's choices. You can think of this nagging inner voice as sort of the brain's equivalent of the Catholic Church, if you're an Austrian like me, or the super-ego, if you're Freudian, or your mother, if you're Jewish.

(Laughter)

Now obviously, the Critic is a key ingredient in what makes us intelligent. So we set out to identify the cells in the fly's brain that played the role of the Critic. And the logic of our experiment was simple. We thought if we could use our optical remote control to activate the cells of the Critic, we should be able, artificially, to nag the Actor into changing its policy. In other words, the fly should learn from mistakes that it thought it had made but, in reality, it had not made. So we bred flies whose brains were more or less randomly peppered with cells that were light addressable. And then we took these flies and allowed them to make choices. And whenever they made one of the two choices, chose one odor, in this case the blue one over the orange one, we switched on the lights. If the Critic was among the optically activated cells, the result of this intervention should be a change in policy. The fly should learn to avoid the optically reinforced odor.

Here's what happened in two instances: We're comparing two strains of flies, each of them having about 100 light-addressable cells in their brains, shown here in green on the left and on the right. What's common among these groups of cells is that they all produce the neurotransmitter dopamine. But the identities of the individual dopamine-producing neurons are clearly largely different on the left and on the right. Optically activating these hundred or so cells into two strains of flies has dramatically different consequences. If you look first at the behavior of the fly on the right, you can see that whenever it reaches the midpoint of the chamber where the two odors meet, it marches straight through, as it did before. Its behavior is completely unchanged. But the behavior of the fly on the left is very different. Whenever it comes up to the midpoint, it pauses, it carefully scans the odor interface as if it was sniffing out its environment, and then it turns around. This means that the policy that the Actor implements now includes an instruction to avoid the odor that's in the right half of the chamber. This means that the Critic must have spoken in that animal, and that the Critic must be contained among the dopamine-producing neurons on the left, but not among the dopamine producing neurons on the right.

Through many such experiments, we were able to narrow down the identity of the Critic to just 12 cells. These 12 cells, as shown here in green, send the output to a brain structure called the "mushroom body," which is shown here in gray. We know from our formal model that the brain structure at the receiving end of the Critic's commentary is the Actor. So this anatomy suggests that the mushroom bodies have something to do with action choice. Based on everything we know about the mushroom bodies, this makes perfect sense. In fact, it makes so much sense that we can construct an electronic toy circuit that simulates the behavior of the fly. In this electronic toy circuit, the mushroom body neurons are symbolized by the vertical bank of blue LEDs in the center of the board. These LED's are wired to sensors that detect the presence of odorous molecules in the air. Each odor activates a different combination of sensors, which in turn activates a different odor detector in the mushroom body. So the pilot in the cockpit of the fly, the Actor, can tell which odor is present simply by looking at which of the blue LEDs lights up.

What the Actor does with this information depends on its policy, which is stored in the strengths of the connection, between the odor detectors and the motors that power the fly's evasive actions. If the connection is weak, the motors will stay off and the fly will continue straight on its course. If the connection is strong, the motors will turn on and the fly will initiate a turn. Now consider a situation in which the motors stay off, the fly continues on its path and it suffers some painful consequence such as getting zapped. In a situation like this, we would expect the Critic to speak up and to tell the Actor to change its policy. We have created such a situation, artificially, by turning on the critic with a flash of light. That caused a strengthening of the connections between the currently active odor detector and the motors. So the next time the fly finds itself facing the same odor again, the connection is strong enough to turn on the motors and to trigger an evasive maneuver.

I don't know about you, but I find it exhilarating to see how vague psychological notions evaporate and give rise to a physical, mechanistic understanding of the mind, even if it's the mind of the fly. This is one piece of good news. The other piece of good news, for a scientist at least, is that much remains to be discovered. In the experiments I told you about, we have lifted the identity of the Critic, but we still have no idea how the Critic does its job. Come to think of it, knowing when you're wrong without a teacher, or your mother, telling you, is a very hard problem. There are some ideas in computer science and in artificial intelligence as to how this might be done, but we still haven't solved a single example of how intelligent behavior springs from the physical interactions in living matter. I think we'll get there in the not too distant future.

Thank you.

(Applause)