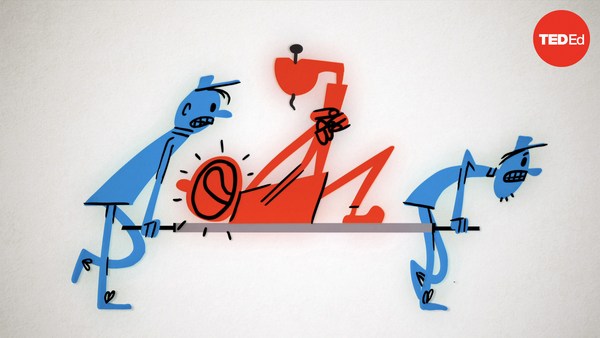

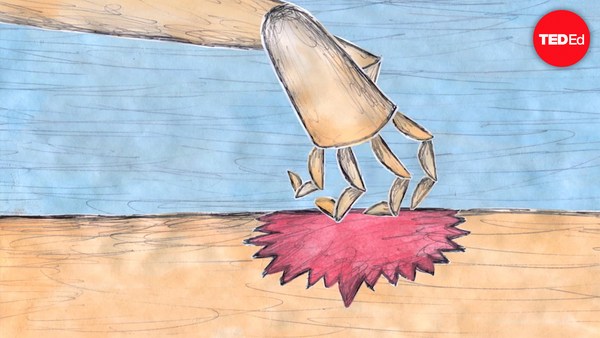

Say you're at the beach, and you get sand in your eyes. How do you know the sand is there? You obviously can't see it, but if you are a normal, healthy human, you can feel it, that sensation of extreme discomfort, also known as pain. Now, pain makes you do something, in this case, rinse your eyes until the sand is gone. And how do you know the sand is gone? Exactly. Because there's no more pain. There are people who don't feel pain. Now, that might sound cool, but it's not. If you can't feel pain, you could get hurt, or even hurt yourself and never know it. Pain is your body's early warning system. It protects you from the world around you, and from yourself. As we grow, we install pain detectors in most areas of our body. These detectors are specialized nerve cells called nociceptors that stretch from your spinal cord to your skin, your muscles, your joints, your teeth and some of your internal organs. Just like all nerve cells, they conduct electrical signals, sending information from wherever they're located back to your brain. But, unlike other nerve cells, nociceptors only fire if something happens that could cause or is causing damage. So, gently touch the tip of a needle. You'll feel the metal, and those are your regular nerve cells. But you won't feel any pain. Now, the harder you push against the needle, the closer you get to the nociceptor threshold. Push hard enough, and you'll cross that threshold and the nociceptors fire, telling your body to stop doing whatever you're doing. But the pain threshold isn't set in stone. Certain chemicals can tune nociceptors, lowering their threshold for pain. When cells are damaged, they and other nearby cells start producing these tuning chemicals like crazy, lowering the nociceptors' threshold to the point where just touch can cause pain. And this is where over-the-counter painkillers come in. Aspirin and ibuprofen block production of one class of these tuning chemicals, called prostaglandins. Let's take a look at how they do that. When cells are damaged, they release a chemical called arachidonic acid. And two enzymes called COX-1 and COX-2 convert this arachidonic acid into prostaglandin H2, which is then converted into a bunch of other chemicals that do a bunch of things, including raise your body temperature, cause inflammation and lower the pain threshold. Now, all enzymes have an active site. That's the place in the enzyme where the reaction happens. The active sites of COX-1 and COX-2 fit arachidonic acid very cozily. As you can see, there is no room to spare. Now, it's in this active site that aspirin and ibuprofen do their work. So, they work differently. Aspirin acts like a spine from a porcupine. It enters the active site and then breaks off, leaving half of itself in there, totally blocking that channel and making it impossible for the arachidonic acid to fit. This permanently deactivates COX-1 and COX-2. Ibuprofen, on the other hand, enters the active site, but doesn't break apart or change the enzyme. COX-1 and COX-2 are free to spit it out again, but for the time that that ibuprofen is in there, the enzyme can't bind arachidonic acid, and can't do its normal chemistry. But how do aspirin and ibuprofen know where the pain is? Well, they don't. Once the drugs are in your bloodstream, they are carried throughout your body, and they go to painful areas just the same as normal ones. So that's how aspirin and ibuprofen work. But there are other dimensions to pain. Neuropathic pain, for example, is pain caused by damage to our nervous system itself; there doesn't need to be any sort of outside stimulus. And scientists are discovering that the brain controls how we respond to pain signals. For example, how much pain you feel can depend on whether you're paying attention to the pain, or even your mood. Pain is an area of active research. If we can understand it better, maybe we can help people manage it better.