Let's imagine a sculptor building a statue, just chipping away with his chisel. Michelangelo had this elegant way of describing it when he said, "Every block of stone has a statue inside of it, and it's the task of the sculptor to discover it." But what if he worked in the opposite direction? Not from a solid block of stone, but from a pile of dust, somehow gluing millions of these particles together to form a statue.

I know that's an absurd notion. It's probably impossible. The only way you get a statue from a pile of dust is if the statue built itself -- if somehow we could compel millions of these particles to come together to form the statue.

Now, as odd as that sounds, that is almost exactly the problem I work on in my lab. I don't build with stone, I build with nanomaterials. They're these just impossibly small, fascinating little objects. They're so small that if this controller was a nanoparticle, a human hair would be the size of this entire room. And they're at the heart of a field we call nanotechnology, which I'm sure we've all heard about, and we've all heard how it is going to change everything.

When I was a graduate student, it was one of the most exciting times to be working in nanotechnology. There were scientific breakthroughs happening all the time. The conferences were buzzing, there was tons of money pouring in from funding agencies. And the reason is when objects get really small, they're governed by a different set of physics that govern ordinary objects, like the ones we interact with. We call this physics quantum mechanics. And what it tells you is that you can precisely tune their behavior just by making seemingly small changes to them, like adding or removing a handful of atoms, or twisting the material. It's like this ultimate toolkit. You really felt empowered; you felt like you could make anything.

And we were doing it -- and by we I mean my whole generation of graduate students. We were trying to make blazing fast computers using nanomaterials. We were constructing quantum dots that could one day go in your body and find and fight disease. There were even groups trying to make an elevator to space using carbon nanotubes. You can look that up, that's true. Anyways, we thought it was going to affect all parts of science and technology, from computing to medicine. And I have to admit, I drank all of the Kool-Aid. I mean, every last drop.

But that was 15 years ago, and -- fantastic science was done, really important work. We've learned a lot. We were never able to translate that science into new technologies -- into technologies that could actually impact people. And the reason is, these nanomaterials -- they're like a double-edged sword. The same thing that makes them so interesting -- their small size -- also makes them impossible to work with. It's literally like trying to build a statue out of a pile of dust. And we just don't have the tools that are small enough to work with them. But even if we did, it wouldn't really matter, because we couldn't one by one place millions of particles together to build a technology. So because of that, all of the promise and all of the excitement has remained just that: promise and excitement. We don't have any disease-fighting nanobots, there's no elevators to space, and the thing that I'm most interested in, no new types of computing.

Now that last one, that's a really important one. We just have come to expect the pace of computing advancements to go on indefinitely. We've built entire economies on this idea. And this pace exists because of our ability to pack more and more devices onto a computer chip. And as those devices get smaller, they get faster, they consume less power and they get cheaper. And it's this convergence that gives us this incredible pace.

As an example: if I took the room-sized computer that sent three men to the moon and back and somehow compressed it -- compressed the world's greatest computer of its day, so it was the same size as your smartphone -- your actual smartphone, that thing you spent 300 bucks on and just toss out every two years, would blow this thing away. You would not be impressed. It couldn't do anything that your smartphone does. It would be slow, you couldn't put any of your stuff on it, you could possibly get through the first two minutes of a "Walking Dead" episode if you're lucky --

(Laughter)

The point is the progress -- it's not gradual. The progress is relentless. It's exponential. It compounds on itself year after year, to the point where if you compare a technology from one generation to the next, they're almost unrecognizable. And we owe it to ourselves to keep this progress going. We want to say the same thing 10, 20, 30 years from now: look what we've done over the last 30 years. Yet we know this progress may not last forever. In fact, the party's kind of winding down. It's like "last call for alcohol," right? If you look under the covers, by many metrics like speed and performance, the progress has already slowed to a halt. So if we want to keep this party going, we have to do what we've always been able to do, and that is to innovate.

So our group's role and our group's mission is to innovate by employing carbon nanotubes, because we think that they can provide a path to continue this pace. They are just like they sound. They're tiny, hollow tubes of carbon atoms, and their nanoscale size, that small size, gives rise to these just outstanding electronic properties. And the science tells us if we could employ them in computing, we could see up to a ten times improvement in performance. It's like skipping through several technology generations in just one step.

So there we have it. We have this really important problem and we have what is basically the ideal solution. The science is screaming at us, "This is what you should be doing to solve your problem." So, all right, let's get started, let's do this. But you just run right back into that double-edged sword. This "ideal solution" contains a material that's impossible to work with. I'd have to arrange billions of them just to make one single computer chip. It's that same conundrum, it's like this undying problem.

At this point, we said, "Let's just stop. Let's not go down that same road. Let's just figure out what's missing. What are we not dealing with? What are we not doing that needs to be done?" It's like in "The Godfather," right? When Fredo betrays his brother Michael, we all know what needs to be done. Fredo's got to go.

(Laughter)

But Michael -- he puts it off. Fine, I get it. Their mother's still alive, it would make her upset. We just said, "What's the Fredo in our problem?" What are we not dealing with? What are we not doing, but needs to be done to make this a success?" And the answer is that the statue has to build itself. We have to find a way, somehow, to compel, to convince billions of these particles to assemble themselves into the technology. We can't do it for them. They have to do it for themselves. And it's the hard way, and this is not trivial, but in this case, it's the only way.

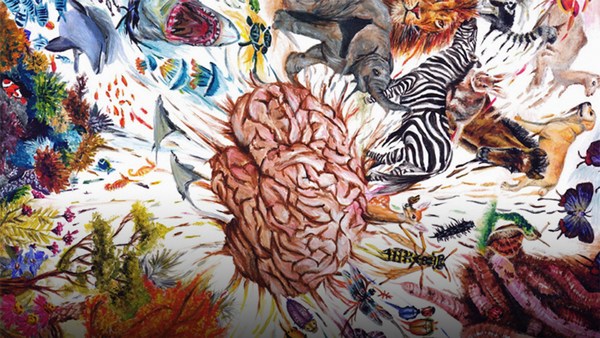

Now, as it turns out, this is not that alien of a problem. We just don't build anything this way. People don't build anything this way. But if you look around -- and there's examples everywhere -- Mother Nature builds everything this way. Everything is built from the bottom up. You can go to the beach, you'll find these simple organisms that use proteins -- basically molecules -- to template what is essentially sand, just plucking it from the sea and building these extraordinary architectures with extreme diversity. And nature's not crude like us, just hacking away. She's elegant and smart, building with what's available, molecule by molecule, making structures with a complexity and a diversity that we can't even approach. And she's already at the nano. She's been there for hundreds of millions of years. We're the ones that are late to the party.

So we decided that we're going to use the same tool that nature uses, and that's chemistry. Chemistry is the missing tool. And chemistry works in this case because these nanoscale objects are about the same size as molecules, so we can use them to steer these objects around, much like a tool. That's exactly what we've done in our lab. We've developed chemistry that goes into the pile of dust, into the pile of nanoparticles, and pulls out exactly the ones we need. Then we can use chemistry to arrange literally billions of these particles into the pattern we need to build circuits. And because we can do that, we can build circuits that are many times faster than what anyone's been able to make using nanomaterials before. Chemistry's the missing tool, and every day our tool gets sharper and gets more precise. And eventually -- and we hope this is within a handful of years -- we can deliver on one of those original promises.

Now, computing is just one example. It's the one that I'm interested in, that my group is really invested in, but there are others in renewable energy, in medicine, in structural materials, where the science is going to tell you to move towards the nano. That's where the biggest benefit is. But if we're going to do that, the scientists of today and tomorrow are going to need new tools -- tools just like the ones I described. And they will need chemistry. That's the point. The beauty of science is that once you develop these new tools, they're out there. They're out there forever, and anyone anywhere can pick them up and use them, and help to deliver on the promise of nanotechnology.

Thank you so much for your time. I appreciate it.

(Applause)