When I was in the fifth grade, I bought an issue of "DC Comics Presents #57" off of a spinner rack at my local bookstore, and that comic book changed my life. The combination of words and pictures did something inside my head that had never been done before, and I immediately fell in love with the medium of comics. I became a voracious comic book reader, but I never brought them to school. Instinctively, I knew that comic books didn't belong in the classroom. My parents definitely were not fans, and I was certain that my teachers wouldn't be either. After all, they never used them to teach, comic books and graphic novels were never allowed during silent sustained reading, and they were never sold at our annual book fair. Even so, I kept reading comics, and I even started making them. Eventually I became a published cartoonist, writing and drawing comic books for a living.

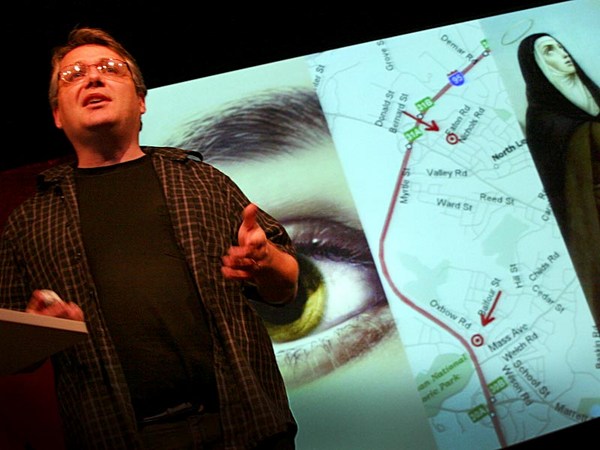

I also became a high school teacher. This is where I taught: Bishop O'Dowd High School in Oakland, California. I taught a little bit of math and a little bit of art, but mostly computer science, and I was there for 17 years. When I was a brand new teacher, I tried bringing comic books into my classroom. I remember telling my students on the first day of every class that I was also a cartoonist. It wasn't so much that I was planning to teach them with comics, it was more that I was hoping comics would make them think that I was cool.

(Laughter)

I was wrong. This was the '90s, so comic books didn't have the cultural cachet that they do today. My students didn't think I was cool. They thought I was kind of a dork. And even worse, when stuff got hard in my class, they would use comic books as a way of distracting me. They would raise their hands and ask me questions like, "Mr. Yang, who do you think would win in a fight, Superman or the Hulk?"

(Laughter)

I very quickly realized I had to keep my teaching and my cartooning separate. It seemed like my instincts in fifth grade were correct. Comic books didn't belong in the classroom.

But again, I was wrong. A few years into my teaching career, I learned firsthand the educational potential of comics. One semester, I was asked to sub for this Algebra 2 class. I was asked to long-term sub it, and I said yes, but there was a problem. At the time, I was also the school's educational technologist, which meant every couple of weeks I had to miss one or two periods of this Algebra 2 class because I was in another classroom helping another teacher with a computer-related activity. For these Algebra 2 students, that was terrible. I mean, having a long-term sub is bad enough, but having a sub for your sub? That's the worst. In an effort to provide some sort of consistency for my students, I began videotaping myself giving lectures. I'd then give these videos to my sub to play for my students. I tried to make these videos as engaging as possible. I even included these little special effects. For instance, after I finished a problem on the board, I'd clap my hands, and the board would magically erase.

(Laughter)

I thought it was pretty awesome. I was pretty certain that my students would love it, but I was wrong.

(Laughter)

These video lectures were a disaster. I had students coming up to me and saying things like, "Mr. Yang, we thought you were boring in person, but on video, you are just unbearable."

(Laughter)

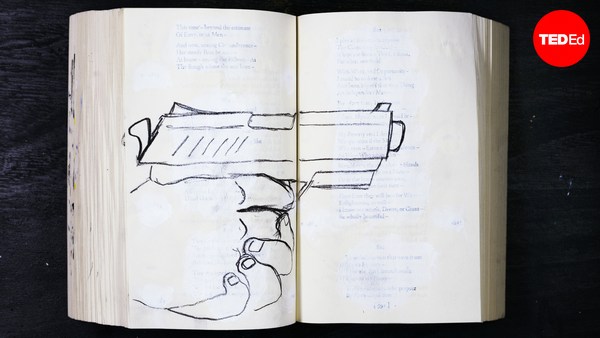

So as a desperate second attempt, I began drawing these lectures as comics. I'd do these very quickly with very little planning. I'd just take a sharpie, draw one panel after the other, figuring out what I wanted to say as I went. These comics lectures would come out to anywhere between four and six pages long, I'd xerox these, give them to my sub to hand to my students. And much to my surprise, these comics lectures were a hit. My students would ask me to make these for them even when I could be there in person. It was like they liked cartoon me more than actual me.

(Laughter)

This surprised me, because my students are part of a generation that was raised on screens, so I thought for sure they would like learning from a screen better than learning from a page. But when I talked to my students about why they liked these comics lectures so much, I began to understand the educational potential of comics. First, unlike their math textbooks, these comics lectures taught visually. Our students grow up in a visual culture, so they're used to taking in information that way. But unlike other visual narratives, like film or television or animation or video, comics are what I call permanent. In a comic, past, present and future all sit side by side on the same page. This means that the rate of information flow is firmly in the hands of the reader. When my students didn't understand something in my comics lecture, they could just reread that passage as quickly or as slowly as they needed. It was like I was giving them a remote control over the information. The same was not true of my video lectures, and it wasn't even true of my in-person lectures. When I speak, I deliver the information as quickly or slowly as I want. So for certain students and certain kinds of information, these two aspects of the comics medium, its visual nature and its permanence, make it an incredibly powerful educational tool.

When I was teaching this Algebra 2 class, I was also working on my master's in education at Cal State East Bay. And I was so intrigued by this experience that I had with these comics lectures that I decided to focus my final master's project on comics. I wanted to figure out why American educators have historically been so reluctant to use comic books in their classrooms. Here's what I discovered.

Comic books first became a mass medium in the 1940s, with millions of copies selling every month, and educators back then took notice. A lot of innovative teachers began bringing comics into their classrooms to experiment. In 1944, the "Journal of Educational Sociology" even devoted an entire issue to this topic. Things seemed to be progressing. Teachers were starting to figure things out. But then along comes this guy. This is child psychologist Dr. Fredric Wertham, and in 1954, he wrote a book called "Seduction of the Innocent," where he argues that comic books cause juvenile delinquency.

(Laughter)

He was wrong. Now, Dr. Wertham was actually a pretty decent guy. He spent most of his career working with juvenile delinquents, and in his work he noticed that most of his clients read comic books. What Dr. Wertham failed to realize was in the 1940s and '50s, almost every kid in America read comic books.

Dr. Wertham does a pretty dubious job of proving his case, but his book does inspire the Senate of the United States to hold a series of hearings to see if in fact comic books caused juvenile delinquency. These hearings lasted for almost two months. They ended inconclusively, but not before doing tremendous damage to the reputation of comic books in the eyes of the American public.

After this, respectable American educators all backed away, and they stayed away for decades. It wasn't until the 1970s that a few brave souls started making their way back in. And it really wasn't until pretty recently, maybe the last decade or so, that comics have seen more widespread acceptance among American educators.

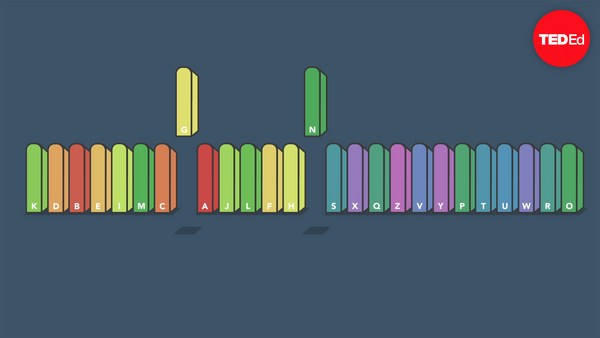

Comic books and graphic novels are now finally making their way back into American classrooms and this is even happening at Bishop O'Dowd, where I used to teach. Mr. Smith, one of my former colleagues, uses Scott McCloud's "Understanding Comics" in his literature and film class, because that book gives his students the language with which to discuss the relationship between words and images. Mr. Burns assigns a comics essay to his students every year. By asking his students to process a prose novel using images, Mr. Burns asks them to think deeply not just about the story but also about how that story is told. And Ms. Murrock uses my own "American Born Chinese" with her English 1 students. For her, graphic novels are a great way of fulfilling a Common Core Standard. The Standard states that students ought to be able to analyze how visual elements contribute to the meaning, tone and beauty of a text.

Over in the library, Ms. Counts has built a pretty impressive graphic novel collection for Bishop O'Dowd. Now, Ms. Counts and all of her librarian colleagues have really been at the forefront of comics advocacy, really since the early '80s, when a school library journal article stated that the mere presence of graphic novels in the library increased usage by about 80 percent and increased the circulation of noncomics material by about 30 percent.

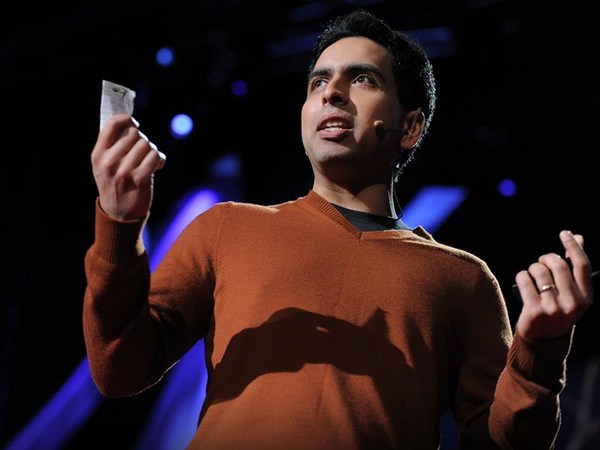

Inspired by this renewed interest from American educators, American cartoonists are now producing more explicitly educational content for the K-12 market than ever before. A lot of this is directed at language arts, but more and more comics and graphic novels are starting to tackle math and science topics. STEM comics graphics novels really are like this uncharted territory, ready to be explored.

America is finally waking up to the fact that comic books do not cause juvenile delinquency.

(Laughter)

That they really do belong in every educator's toolkit. There's no good reason to keep comic books and graphic novels out of K-12 education. They teach visually, they give our students that remote control. The educational potential is there just waiting to be tapped by creative people like you.

Thank you.

(Applause)