I once watched this video of a relay race at a primary school in Jamaica. You see here, there are two teams, the Yellow team and the Blue team. And the kids are doing great, working so hard and running so fast. And the Yellow team has the lead, until this little boy gets the baton and runs in the wrong direction. My favorite part is when the grown-up chases him, looking like he's about to pass out, trying to save the situation and get the kid to run in the right direction.

In many ways, that's what it's like for many young people in Africa. They're many paces behind their peers on the other side of the inequality divide, and they're also running in the wrong direction. Because as much as we might wish otherwise, and aspire to build economic and social systems where it’s not the case, global development is a race. And it's a race that my home country, Nigeria, and home continent, Africa, are losing.

Inequality must be seen as the global epidemic that it is. From the boy who cannot afford to dream because of the disappointment that could come with it to the girl that skips school in order to sell snacks in traffic, just to fund her school fees. It is clear that inequality is at the center of many of the world's problems, affecting not just the bottom 40 percent of us, but everyone. Young men and women who don't get set on the path of equal opportunities become frustrated. And we may not like the choices they make in their attempt to get what they think they rightly deserve or punish those that they assume keep them away from those better opportunities.

But it doesn't have to be this way if we, as humanity, make different choices. We have the ability we need to fill that opportunity gap, but we just have to prioritize it.

I grew up many paces behind. Even though I was a smart kid growing up in Akure, a town 350 kilometers from Lagos, it felt like a place that was disconnected from the rest of the world, and one where hope and dreams were limited. But I wanted to get ahead, and when I saw a computer for the first time, in my high school, I was spellbound, and I knew I just had to get my hands on whatever it was. This was in 1991, and there were only two computers for the entire school of more than 500 students. So the teacher in charge said computers were not for people like me, because I wouldn't understand how to use them. He would only allow my friend and his two brothers, sons of a professor of computer science, to use it, because they already knew what they were doing.

In university, I was so desperate to be around computers that to make sure I had access to the computer lab, I slept there at night, even when the campus was closed due to teachers' strikes and student protests. I didn't own a computer until I was gifted one in 2002, but what I lacked in devices, I made up for in drive and determination.

However, camping out in computer labs in order to teach yourself coding isn't a systemic solution, which is why I started Paradigm Initiative, to help all Nigerians learn to use technology to help them run faster and further toward their hopes and dreams, and help our nation and take our continent great leaps forward in development.

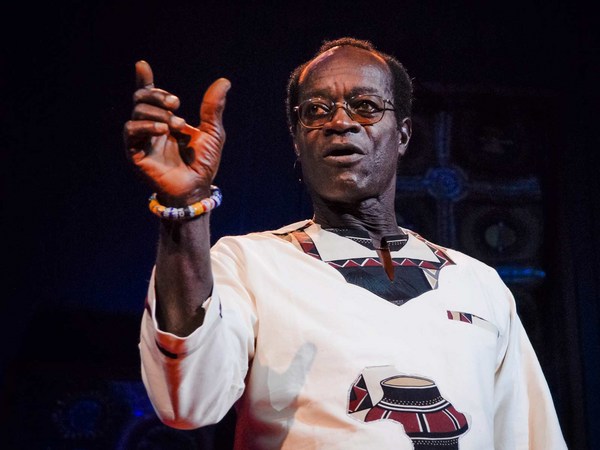

You see, to put it as simply as possible, my goal is for everyone in Africa to become Famous'. I don't mean, like, a celebrity, I mean I want everyone to be like Famous, this guy. When Famous Onokurefe came to Paradigm Initiative, he had completed high school, but couldn't afford college, and his options in life were limited. When I asked Famous recently about where he would have been without our training program, he rolled out a list of could-haves, including ending up on the streets, jobless and homeless, at the risk of doing things he wouldn't be proud of. But luckily, Famous came to Paradigm Initiative, in 2007, because his friends, who were part of a youth group I'd told about my plans, kept talking about a free computer training program. And during his training, Famous paid close attention and excelled.

When the United Kingdom Trade and Investment team at the UK Deputy High Commission in Lagos asked us to recommend a few potential interns, we recommended Famous and a few others to be interviewed. He got the internship, and while there, he heard about an Entry Clearance Assistant job at the [British] High Commission in Abuja. He applied, even though, without a college degree, no one thought he had a shot. He was starting behind, but it wasn't technology that helped him get ahead, it was the extra training, training rooted in his community, training that understood his context and his challenges, training that helped him change his life for the better.

Famous got the job, and then saved enough to pay his way through university. Famous, a Medical Biochemistry graduate from Delta State University, is now a chartered accountant and an assistant manager with one of the world's Big Four professional services firms, where he has won innovation awards consecutively for the last four years. But let's be clear ... the computer didn't do that -- we did.

Without our additional training and support, Famous wouldn’t be where he is today. Fairness is not giving everyone a computer and a special program, fairness is helping make sure everyone has the same access and training that can help them make use of all these things to improve their lives. When people are further behind, fairness isn't giving everyone the same opportunity to compete, fairness is helping those who are behind to get to the same starting line with everyone else and giving them a chance to run their own race in the right direction. Yet there are millions of young people who have not been as fortunate as Famous and I, who still don't have the skills, let alone the will, to face similarly insurmountable inequality.

As more workers and students now have to complete tasks or learn from home, this inequality is exponentially pronounced, and with dire consequences. This is why I do what I do through Paradigm Initiative.

But just like many intervention programs, there's a limit to how many young people we can reach through our three centers. We've now taken the training to where the kids are, but public schools are so ill-equipped that we have to bring devices, access, and in many cases, we have to provide power supply.

Since 2007, we've worked with young Nigerians in order to improve their lives and that of their families. To give just one example, Ogochukwu Obi father kicked her, her sisters and her mom out, because he preferred to have a son. But when she completed our program, got a job and became her family's breadwinner, her father came calling, admitting that he was wrong about the worth of the girl.

In addition to our work at our training centers and in schools, we're now planning to acquire mobile learning units, busses equipped with access, with devices, and with power, and that can serve multiple schools. Yes, we need better access to technology and policies that facilitate open internet access, freedom of expression and more, but the best computers in the world could fall in a democratic forest, but no one would hear them, let alone use them, if they were miles away, hauling water from a well or foraging for scrap metal to pay school fees in a school that can’t even teach them computer skills. Just like the fanciest sneakers in the world can’t help a runner miles behind everyone else.

I'll never forget being invited back to my high school while I was Nigeria's Information Technology Youth Ambassador. It was 10 years after I had been denied access to using the computer in that very same school. But here I was, being introduced as a role model who was supposedly shaped by the same school. After my presentation, that teacher, who said I could never understand how to use computers, was quick to grab the microphone and tell everyone that he remembered me as a student and he was sure I had it in me all along. He was right. He didn't know it at the time, but I did have it in me. Famous had it in him, Ogochukwu had it in her, the bottom 40 percent have it in them. Are we going to say that life-changing opportunities are not for people like them, like that teacher said? Or are we going to recognize that centuries of inequality can’t just be solved by gadgets, but by training and resources that fully level the playing field?

Fairness is not about giving every child a computer and an app, fairness is connecting them to access, to training and to additional support, for the need to take equal advantage of those computers and apps. That's how we pass them the baton and help them catch up and start running in the right direction, and change their lives.

Thank you.